Musician Dom Flemons talks about using the banjo in performance. With him is, from left, UNC ethnomusicologist Robert Cantwell, Duke professors Louise Meintjes and Laurent Dubois, Flemons and banjo builder Pete Ross. Photo by Eric Barstow

While the banjo is seen in a multitude of musical genres today, the instrument’s history has the deepest roots in African culture during the enslavement times of the 17th century, in which it served as a tool to bring about solidarity and community, panelists discussed during a Faculty Bookwatch Tuesday evening.

Moderated by Franklin Humanities Institute Director Deborah Jenson and co-sponsored by Duke University Libraries, the event centered around Laurent Dubois’ latest book, The Banjo: America’s African Instrument with a panel discussion between Laurent Dubois himself, musician Dom Flemons, banjo-builder and musician Pete Ross, and ethnomusicologists Robert Cantwell and Louise Meintjes. After a lively performance by Dom Flemons on the banjo and quill, panelists explored the Caribbean history of the banjo and its power to unify.

Panelists emphasized how the banjo’s versatility as an instrument provided it with the capacity to truly encapsulate the heart of African culture.

“The banjo does in fact embody one of the principles that goes through the heart of music in West Africa, which is rhythm and melody are joined together in an instrument that is both a string instrument and a drum,” Cantwell said.

“All of the energy of a beat is there. The energy seems to spring right from the hands and the heart of the musician.”

Discussion continued on Dubois’ book was intended as more than an exhaustive historical recollection on the instrument. “The book was written with love for banjos, with love for the musicians, and with love for the buzz. And for that, I thank Laurent.” Meintjes said.

“Those who say the instrument materializes history, trying to recreate something that is missing from our view from history, we miss this cultural thing. But Laurent places the banjo in its cultural and spiritual context,” Ross said.

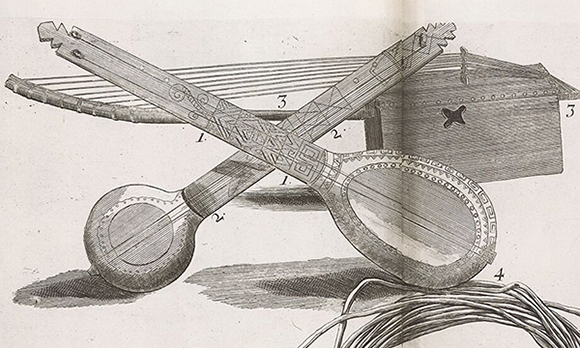

A contemporary recording of a song recorded on a traditional Haitian banza.

Dubois said his inspiration for the book came out of his interests in Haitian and Caribbean history, and he explored the questions behind the banjo’s origins and traditions. What seems enigmatic is the banjo's ability to unify and build a community in environments as diverse as 17th century slave culture, Appalachian music and the Greenwich folk scene. In all of these contexts, panelists said, the banjo has a capacity to voice a rhythm and melody that reaches out to many people.

“One thing I admire about Laurent’s book is that he addresses several deep mysteries,” Cantwell said. “He preserves them as mysteries, and if anything, he deepens them as mysteries and allows us to probe them with our own imaginations.”

“The banjo has always, from the very beginning, had meaning behind it … If you think about the banjo in the way that the banjo is thought about in terms of race, you’re getting at the heart and the node of our culture. I realized that the Caribbean held the key to this mystery.” Dubois said. “The story of the banjo, we knew that it had African inspiration, and we also understood that it had been a part of African American culture. But in a sense, there was this missing piece of the story. And that story was of the 17th and 18th century.”

Below: Don Flemons gives a banjo lesson at the session.