New Department of English faculty member Tsitsi Jaji in a seminar she's teaching this semester. Photo by Megan Mendenhall/Duke Photography

Read MoreAmong Tsitsi Jaji’s memories of growing up in Harare, Zimbabwe, one moment in particular shines bright: She is in a packed concert hall, dressed in a home-made purple gown, and she’s stepping onstage to perform as a solo pianist with the city’s symphony orchestra.

At the time, the teenager was focused on the challenges of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. Only later did she realize the event was also a “first.” Jaji was the first woman of color ever to perform as a soloist with the orchestra in Zimbabwe’s capital city.

“At the time, no one sat me down and said, ‘Okay, the people in the audience may have a whole bunch of feelings about seeing a little black girl up there,’” Jaji says with a laugh. “But in retrospect, I realized I was part of this amazing moment in history when a lot of things were changing.”

As the daughter of an American mother and a Zimbabwean father, and a member of Zimbabwe’s first raciallyintegrated generation, Jaji grew up bridging cultures. She continues to seek out threads of connection across cultures in her work as a literary scholar and a new member of the Duke English faculty, where she is an associate research professor of English.

Jaji grew up mainly in Zimbabwe before coming to the United States to attend Oberlin, where she could pursue her love of literature and her devotion to music. She later freelanced as as a musician – playing jazz, gospel, reggae and anything else that paid -- before returning to graduate school to study literature.

Her two twin loves of music and literature still dominate her life and her scholarship, where she finds surprising connections between the two.

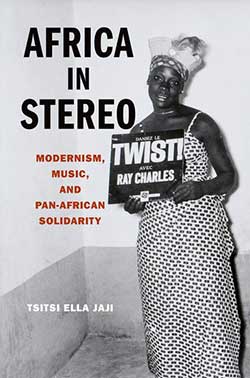

Her first book, “Africa in Stereo: Modernism, Music and Pan-African Solidarity,“ looks at the influence black American popular music had on the African continent in the 20th century, particularly in Ghana, Senegal and South Africa.

Throughout the 20th century, African-American music spread across Africa via hymnals,radio shows and LPs, Jaji says. African cover bands played the music of American bands note for note, sometimes adopting the names of African-American groups such as the Ink Spots and the Moonglows.

The book’s cover shows a smiling womanwearing a modish version of a traditional costume, and holding up a French version of a Ray Charles record, “Dancer Le Twist.” For Jaji, the cover helps illustrate one of the book’s key points: In the 20th century, African-American music gave Africans a point of connection to a wider world. The music also became something of a soundtrack for burgeoning pan-African movement on the continent, she said.

She also likes the image because it departs from the sorts of pictures Westerners have come to expect from Africa, she said.

“It’s a very different image of an African woman than what generally circulates, right?” Jaji said. ”She’s not hungry, she’s not got flies on her face, there’s no kid on her back, no water on her head.”

“Those are important stories to tell as well,“ Jaji said. “But there’s something human about culture that connects across gaps that statistics really don’t. These stories give a thicker sense of African identities and black identities.”

Like her earlier book, Jaji’s two current projects explore surprising connections. The first, “Cassava Westerns,” looks at how the American cowboy motif and other tropes of the American West travelled across the globe, influencing music, film and literature in Africa, the Caribbean and black Europe.

Her second project considers the intersection of music and literature. “Classic Black: Art Songs of the Black Atlantic” looks at the important role art songs played in the African-American community in the 20th century. The book profiles black composers who set works by African-American poets to music. Examples include Nina Simone’s setting of the Paul L. Dunbar poem “Compensation” and Florence Price’s setting of poems by Langston Hughes.

Among other things, art songs were an important source of material for black classical singers shut out of the world of opera, she notes.

“Marian Anderson sang art songs in part because she knew operatic roles would be slow in coming,” Jaji says.

Within African-American studies, much attention has been paid to popular and vernacular music, Jaji says. By focusing on classical music, Jaji brings attention to a neglected corner of African-American culture.

“Classical music has often been viewed as white,” Jaji says. “And unfortunatelywithin the academy, folks who really care about black creativity are reinforcing this erasure of musicians who are already marginalized.“

The project also allows her to revisit her own, somewhat complicated relationship to classical music.

“As a conservatory student, I felt some ambivalence playing Schumannwhen I’d grown up in Zimbabwe and our economy was collapsing,” Jaji said. “So in a way it’s a recovery project.”

If finding surprising threads of connection is a theme of Jaji’s scholarship, it also affects her view of teaching. At Duke, for instance, she looks forward to helping African and African-American students find common ground.

“When I moved to the U.S., one of the tensions I saw was between African students and African-American students,” Jaji said. “We don’t like to talk about it, but here there’s potential to have a conversation.

“I think students need some tools to help them make sense of real differences, and to find value in each others’perspectives.”