Millions of African-Americans left the rural South during the 20th century in search of greater opportunities for work, education and overall quality of life in the urban North, Midwest and West.

But the gains many made were clouded by an increased mortality rate, likely the result of unhealthy habits picked up by vices common in the big city, finds a new study led by Duke University.

The study found that if an African-American man lived to age 65 the chances that he would make it to age 70 if he remained in the South were 82.5 percent; if he migrated to the North the chance of surviving to age 70 dropped to 75 percent -- about a 40 percent increase in mortality.

For an African-American woman who lived to age 65, the chances that she would make it to age 70 if she remained in the South were 90 percent; if she migrated to the North, the chance of surviving to age 70 dropped to 85 percent -- about a 50 percent increase in mortality.

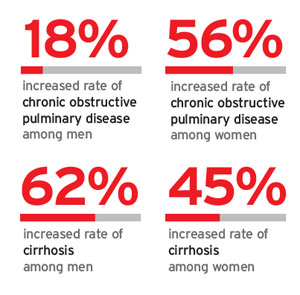

"Something about living in the city, it's very stressful and as a result, people pick up bad habits they think will ease that stress, like smoking and drinking," said co-author Seth Sanders, an economist at Duke. Common causes of death identified for the migrants were connected to behavior choices such as cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and cirrhosis of the liver.

The authors believe the paper is the first attempt to establish a link between the Great Migration and mortality.

Sanders said the findings also have implications for similar migrations today in the developing world, where people are leaving rural inhabitants in search of a better life in more urbanized areas in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, for example.

"We see increases in smoking and drinking in developing countries," he said. "It's not like living in the city has to be bad for your health. I think a lot of it is connected to behaviors -- cities tend to breed bad habits."

Migrants did earn more money by moving north, Sanders said, but they also "self-medicated" with cigarettes and alcohol because they could afford them and had easier access than in the rural South.

"We were surprised with the findings," Sanders said. "We know that education is related to better health; we could have found that people who moved north lived longer. We expected it to be better because they had every advantage – better jobs, education and access to health care."

At the height of the migration in the 1940s and 50s, smoking was associated with the affluent, and blacks were less inclined or able to buy cigarettes, he said.

"The Impact of the Great Migration on Mortality of African Americans: Evidence from the Deep South," appears in the February issue of American Economic Review. Co-authors were from the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan and Carnegie Mellon University.

The findings are based on an analysis that uses proximity of birthplace to railroad lines as an instrument for migration. The mortality rates were compared to blacks born at the same time as migrants who remained in the South until they were 65 or older.

The study noted the Great Migration significantly shaped social and economic advancement of African-Americans in the 20th century, which also contributed to the civil rights movement, Sanders said.

Graphics by Jonathan Lee. See the entire infographic on the Duke Research blog here.