The game of grapevine, or telephone, is a good way to describe how misconceptions about the Higgs particle, and other scientific discoveries, spread in the media.

Duke physicist Mark Kruse says he understands that misconceptions in science can happen, especially in the case of the Higgs, where researchers are trying to translate the terms of complex mathematical equations into everyday English. But that doesn't mean he will let them slide.

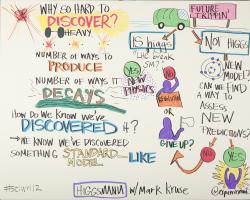

A recent presentation he made to science journalists got him thinking about the misconceptions he's seen reported in the media. And it also encouraged him to join Twitter as @markckruse to share his ideas about how to describe the physics he is doing and comment on the latest particle physics results.

Here's a quick hit list of the inaccuracies Kruse says he's come across so far:

1. Misconception: The Higgs particle gives other particles mass.

Correction: The masses of fundamental particles come from interactions with the Higgs field.

"You see this statement all the time, but how would another particle even 'give' another particle mass?" Kruse asks, explaining truly it's the Higgs field that provides mass to fundamental particles, such as quarks, electrons and neutrinos.

The Higgs particle is a consequence of the Higgs field. By discovering the Higgs particle, it shows the Higgs field exists. In the math that physicists use to understand the Higgs boson and field, there is a piece of an equation that they interpret as the existence of a Higgs boson, which they see as a point-like particle resulting from the Higgs field "curling in" on itself, like a knot in a spider's web. Physicists can't interpret the Higgs boson itself to be giving anything mass, but by interacting with other particles, they can argue that the Higgs field is giving resistance to the particles' motion, thereby giving them mass.

2. Misconception: The Higgs field generates the mass of everything.

Correction: The Higgs field generates the mass of about one percent of observable matter and possibly all of dark matter.

The Higgs field generates mass for quarks, which are the building blocks of protons and neutrons. The protons and neutrons, in turn, form the nuclei at the core of atoms, which are the building blocks of molecules, proteins, cells, plants, animals, planets, stars, galaxies and all the stuff we see in the universe. The mass of quarks accounts for only one percent of the mass of a proton or neutron. The other 99 percent of the mass of observable matter comes from the energy that binds protons' and neutrons' constituent quarks together.

It may seem kind of strange to think that the discovery of the Higgs boson, and thereby the existence of the Higgs field, means scientists have discovered an explanation for only one percent of the observable mass of everything we see. But, "that one percent is the mass of the fundamental constituents of the universe," Kruse says, adding that the Higgs field has also incredible consequences for the structure of atoms and molecules. "If the already small mass of electrons was zero, as it would be without a Higgs field, then everything would just disintegrate," he says. "All the atomic structure we are familiar with wouldn’t exist. We wouldn’t exist. There may still be matter, but it wouldn’t be the same. There certainly wouldn’t be life as we know it."

Also, unobservable matter also wouldn't have mass. Scientists believe this unseen, or dark matter, comprises more than 80 percent of the matter of the universe, but it doesn't interact strongly enough with anything to allow its direct observation. Yet, because it has significant mass, "it must interact with the Higgs field and that's another key point," Kruse says. "The Higgs field generates about one percent of observable mass, with the term 'observable' being a very important qualifier, because the Higgs field may be responsible for the mass of all dark matter."

3. Misconception: The Higgs boson creates the Higgs field.

Correction: The Higgs field generates the Higgs boson.

Kruse says that some of the best physics writers have shared this misconception, but the Higgs boson does not create the Higgs field. The opposite is true, because the Higgs boson is a consequence of the Higgs field. The field itself became noticeable to fundamental particles existing in the very early universe about a billionth of a second after the Big Bang, when a fundamental symmetry in the universe, called the electroweak symmetry, broke.

4. Misconception: The Higgs field is what scientists used to call the aether.

Correction: The Higgs field isn't a medium; it's a field of energy.

In the late 1800s, scientists conceived of the aether as a way to explain how light spreads through space. At the time, scientists reasoned that because sound waves needed a medium through which to travel, then so should light. "With the advent of the theory of relativistic electrodynamics, the need for an aether disappeared," Kruse says.

When physicists and writers try to explain the Higgs field, they often describe it as an "icky, gluey" medium where, as particles move through it, the resistance they experience generates their mass. "It's not a horrible way of thinking about it, except that the field is not any type of sticky mechanical substance. It's not a medium, but rather a type of energy that uniformly pervades all of space," Kruse says.

5. Misconception: There was a "eureka moment" for discovering the Higgs boson and the existence of the Higgs field.

Correction: There will never be eureka moments for discoveries such as the Higgs boson and the Higgs field at the Large Hadron Collider.

"I think this experimental misconception is a whole story in itself," Kruse says. "The discovery is based on a laborious accumulation of evidence, which at a certain point we deem strong enough to claim victory, based on a very low probability that it could be due to something else," he says, adding that "there's no single eureka moment where we look at an event and say that's a Higgs."

Based on his talk in Raleigh and other exchanges with the media, Kruse says reporters are aware that they can often misinterpret information. He says he was impressed with how many came up to him after his talk and asked for better ways to explain the physics they were writing about. "What we see in the media is a transcription of what they are hearing, who they have talked to and how they actually write it down," Kruse says.

By adding his voice on Twitter and other places, he says he's hoping to help correct some of the misconceptions about the Higgs and future discoveries from the Large Hadron Collider and ultimately improve the grapevine of science reporting.