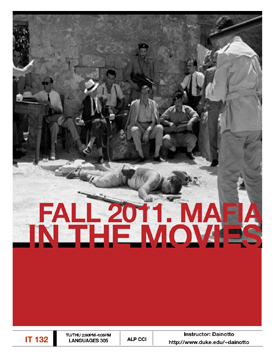

Of the 15 course-advertisement flyers dotting the bulletin board on the second floor of Duke's language building, just one depicts a blood-covered gangster face down in a courtyard.

"It's an image that really catches your attention," Duke professor Roberto Dainotto says. And it's an inkling of things to come for students interested enough to sign up for Dainotto's course, which he could have given a boring name like "Italian History and Culture."

Read MoreInstead, it's "Mafia in the Movies," a Romance studies course in Italian history told through nearly a century of Italian and American mafia films.

Why a film course? Italian history is, well, history. The mafia, on the other hand? Dangerous, mysterious, sexy.

For an academic department trying to reach students from majors outside the humanities, it doesn't hurt to invoke some edgy subject matter. Or design a flyer that's a black-and-white screen shot from the 1962 Italian mafia film "Salvatore Guiliano," one of more than a dozen films that Dainotto's students are watching this semester.

"We need to bring students in who are not necessarily attracted by the humanities," Dainotto explains. "The mafia is a good, attractive topic."

The class is one of several in Romance studies attempting to broaden the department's reach, and is set against the backdrop of a recent, larger Duke effort to bolster the humanities. That initiative, Humanities Writ Large, is a five-year plan to change the role of the humanities in undergraduate education and link seemingly disparate discliplines. It is fueled by a $6 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

"We have low and very porous fences at Duke and we believe in crossing a lot of boundaries," said Srinivas Aravamudan, dean of the humanities. "Humanities Writ Large is very much about taking some of the core ideas of the humanities and exporting them elsewhere, and the mafia course was doing that even before we got this grant."

At the Movies

The classroom is largely quiet on the first day of Mafia in the Movies. It's a small group of about 10 students, thanks to an end-of-summer scheduling glitch that forced Dainotto to list the course later than usual. He usually attracts 30 to 40 students to the course.

The class begins with stark imagery: several movie clips of snipers aiming and shooting at targets. There's "Dirty Harry," "The Bourne Identity" and even a video game that Dainotto's teenage son is fond of playing.

Dainotto glides through a quick history of the mafia. He shows clips from "Scarface" -- the popular 1983 Brian De Palma remake -- and one from the 1928 Buster Keaton film "The Cameraman."

He keeps asking questions. He keeps getting silence.

He offers up a joke: "In a class on the mafia, it's no good if you don't talk, you know what I mean? It might make me suspicious."

Semi-nervous chuckles.

He moves on.

From the Arcane to the Epic

For Dainotto, movies offer a mechanism to tell two stories: the 20th century emergence of Italian organized crime, and the growth and maturation of Italy itself.

He uses a range of movies, from arcane, black-and-white Italian language films from the early 20th century to, of course, "The Godfather," the Marlon Brando epic.

He often asks students to consider how Italy is depicted at a certain point in time, because doing so is a glimpse into how Italians viewed themselves. In "The Godfather," an American film, Sicily appears warm, beautiful, bucolic and lush. In "Placido Rizzotto," an Italian film depicting the same time period, Sicily appears dark, dirty, cold and grim.

Other classes focus on the sociology of the mafia and reasons why people were, at times, okay with organized crime. Dainotto leans heavily on the 1959 writings of British author Eric Hobsbawn, who saw the mafia as a sort of Robin Hood, its crimes accepted by the citizenry because they challenged government, police or other institutional powers.

Later in the semester, the class studies the 1860s writings of Giovanni Verga, who was obsessed with money and power -- themes that would later emerge in mafia lore. Dainotto uses film segments and scholarly writings to illuminate the emergence and transformation of Italy and its culture.

Dainotto uses the mafia's slow, steady emergence as a way to explain divisions between northern and southern Italy in the 1800s. The north was considered more developed and cosmopolitan. The south, below Naples and including Sicily, was considered mysterious, dangerous and largely lawless.

Shifting Academic Focus

Duke's romance studies department is shifting its focus from the strict and narrow needs of its majors to offering courses that intrigue students from myriad disciplines. The idea, Dainotto says, is to give students an education more comprehensive than a simple major permits.

Some courses utilize popular mainstream topics as a hook. Others link the humanities to other disciplines, like an Economics of Literature course and a French/neuroscience course called "Flaubert's Brain."

In Dainotto's class, the interdisciplinary focus plays out in small ways. Four of Dainotto's students have yet to choose their majors; five others have majors across the academic spectrum.

Two are Italian majors, though each has a second major as well -- physics and economics, respectively.

A third is studying psychology, a fourth is in economics, and one particularly ambitious student has pieced together the unlikely double major of physics and religion.

That's Jacqueline Bascetta, a senior who until this semester was too busy to dabble much in language and culture classes.

But as an Italian-American who grew up in New York City, Bascetta identifies with the stories, myths, fables and folklore of the mafia.

"I called my dad and said, 'Dad, I'm studying our family,'" Bascetta recounts. She is kidding, to be clear. But that's not an unusual joke for Italian-Americans from the Northeast to make, so prominent is the mafia's place in that region's culture and history.

So Bascetta enrolled in Dainotto's class, one small victory for a department in expansion mode.

Much of the students' final grade hinges on a semester-long research paper. Dainotto leaves the topic wide open, asking just that they tie it to what they've learned in class. This freedom is another attempt to get students to tap into their own areas of expertise, wherever they may lie.

Senior Amir Malek, a Robertson Scholar from New Zealand, grew up rooting for AC Milan, a prominent Italian soccer team. His research paper will address the emergence of organized crime in professional sports. He'll zero in on the increasing mafia influence on professional soccer in Italy, linking it to the sport's global reach and the proliferation of rich television contracts, he said.

"The course made me think about the economics of the mafia," Malek writes in an email. "And it begged the question: why is the mafia not more involved in such a lucrative and popular sport?"

One hopes Malek gets the paper done on time. It's due the last day of class, and if Dainotto's course syllabus is any indication, there's no wiggle room.

It is, the syllabus states, "A deadline you can't refuse."