This is all Uncle Charlie's fault.

In the late 1960s, he took his young nephew, Gregg Gunnell,

to a stone quarry outside Sylvania, Ohio

to crack rocks and look for trilobites. The boy became hopelessly

infected with fossil fever.

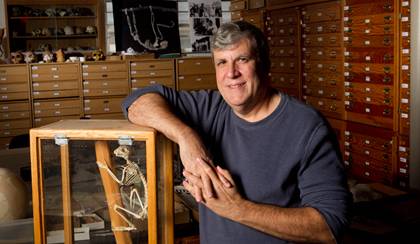

"I found a few trilobites and that was it," says

Gunnell, now 57, the new director of the Division of Fossil Primates in the

Duke Lemur Center. "I thought 'You can find evidence of life in rocks?

This is really cool!'"

And then, when he took anthropology as an undergraduate at

the University of Michigan a few years later, Gunnell also discovered "you

can actually make a living at this."

He has, in fact. After a distinguished 24-year career at

Michigan's Museum of Paleontology, Gunnell is taking over leadership of Duke's

collection of more than 24,000 fossil specimens, including what is probably the

world's largest and most important collection of early anthropoid primates (the

group that includes living monkeys, apes and humans), the life work of recently

retired director Elwyn Simons.

Despite its name, the collection is nowhere near the Lemur

Center. It sits in an unassuming 1960s cinderblock building on Broad Street

across from Joe Van Gogh's north of East Campus. Gunnell hopes to encourage

more students and scholars inside and outside of Duke to make the trek and use

the collection for study. "No place has the collection that Duke has. I

want to raise its visibility and access to its collections."

Since arriving in Durham just a few weeks ago, Gunnell has begun

spearheading a grant application with several North American museums to secure

National Science Foundation funding for digitizing primate fossils, an effort

Duke would lead. It would include making 3-D scans of specimens, all of which

someday will be globally available for study via the Internet.

"This is a great big, huge collection of fossil

primates from the northern dessrt of Egypt," he says, pulling one golf-ball

sized 35 million year old skull out of a drawer at random. His office is still bare, save for a single

book, "Mammal Teeth."

The Duke collection's greatest strength comes from decades

of expeditions to the Fayum desert of Egypt that were led by former director

Simons and master specimen preparator Prithijit Chatrath. He is still at his

workbench in the back room of the collection, meticulously picking sandy matrix

off a tiny mandible under a giant magnifying glass. Gunnell had joined Simons

and Chatrath in the field in 1983 and saw first-hand the treasures of the

Fayum.

The other aspect of the collection which is probably

unmatched anywhere is its skeletal specimens of extinct giant lemurs from

Madagascar, most dating only 500 to 8,000 years in the past. They were big,

slow, and quite possibly delicious, disappearing from the island at about the

same time that humans arrived.

Leadership of the collection "is an important position

for a lot of people on campus," said Lemur Center Director Anne Yoder, and

Gunnell was an obvious choice to succeed Simons. "He has worked at field

sites all over the planet," has a global network of collaborators and is

known for taking students into the field, she said.

Gunnell's other passion for the moment is ancient bats,

which are the only mammals to have mastered powered flight in combination with sonar

echolocation. He found one gorgeously preserved in a lake bed deposit in

Tanzania in 2000 and decided to write it up. "I discovered that there's

almost nobody studying fossil bats, which led to a completely new career."

So far, Gunnell's earliest bat is a 52 million year old bug-eating flier named

Onychonycteris (clawed wings). There may be some surprises among the Egyptian

bats Simons brought to the collection, he said.

The attraction to the Duke post was immediate, Gunnell said.

"I felt like this place was really alive and interesting," he said,

in a room filled with the evidence of tens of thousands of former lives.