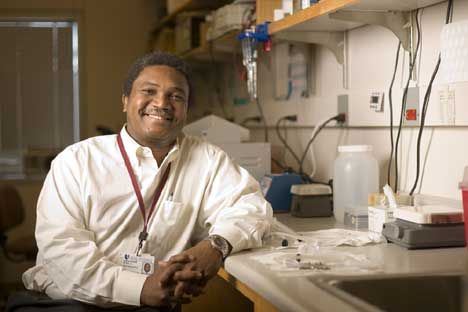

As a young man, Jude Jonassaint, the research manager and clinical research coordinator at Duke's Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center, faced a difficult choice. At first, he thought he would become a missionary, and had made plans to leave his native Haiti for the Congo after he graduated from missionary school.

But when his first brother died from AIDS, he felt he could make a bigger difference through medicine. He entered a nursing program and over the next decade took preparatory courses for medical school. In December 1990, he graduated from the nursing program.

After the death of his brother, however, Jonassaint decided to pass on medical school and go into clinical research instead, in hopes of serving more patients than he could as an individual physician. "I was always looking for ways to improve the care provided to everyone," Jonassaint said. "Per patient is OK, but what about the population still suffering? Instead of thinking I can help one out of 50, I say why not help the whole 50." At Duke, Jonassaint recruits patients to participate in clinical trials. The participation is voluntary, and the center's staff works to not only build a rapport with the patients but to include them in the research process. Some patients go to conferences and collaborate with the researchers on publishing findings.

"Our patients want to know about the disease, as much as we do," Jonassaint said. "We are partners in life and research."

Jonassaint, who is married and has three children, is also active in the community, and his time away from work includes feeding and sheltering families in need. For his efforts, he recently was awarded the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award, given by Duke for significant contributions to the community and to those who lead lives of integrity.

"To reach his goals, Jude has always risked everything he has -- his security, his health and his precious time with his family," said Provost Peter Lange. "He has done all of this because of his love for mankind."

Jonassaint, 49, had to deal with personal tragedy as he pursued his goals. In addition to losing one brother to AIDS, both his parents passed away during the 1990s and his second brother contracted HIV and later died.

He spent many years preparing for his current job by working in a variety of medical-related units, including intensive care, surgery and psychiatry. Additionally, he enrolled in several online courses and training programs to learn the art of analyzing data.

"I study all the time; I gather data, all in hope of alleviating the suffering that people with sickle cell disease often go through," Jonassaint said.

His diligence paid off when in 2002 he was hired as a clinical researcher at the Duke Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center.

"He came to work with a great attitude. He's always looking ahead at what more could be done and is always giving encouragement to others," said Dr. Laura M. De Castro, director of adult sickle cell disease patients clinical activities at Duke, in a letter nominating Jonassaint for the Sullivan award.

While others praise Jonassaint for what he has accomplished, he doesn't see it like that.

"Right now, I'm satisfied with the approach to the problem of sickle cell disease," Jonassaint said. "But with the overall solving of the problem, no. There is so much more to do, so much help is needed."

Torry Bailey is a recent graduate of North Carolina Central University who is interning this summer in Duke's Office of News & Communication.