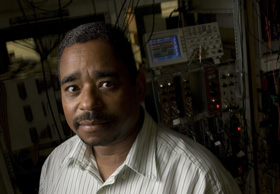

Calvin Howell, a Duke University physics professor who has long championed bringing more minorities into his field, is the new director of the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory (TUNL), which serves nuclear physicists from three Triangle-area research universities.

Howell succeeds Werner Tornow, TUNL's director for the past decade, who in the last year of his leadership saw the Duke-based facility named a "Center of Excellence" by the U.S. Department of Energy, which supports the lab.

Previously TUNL's deputy director, and a researcher there since 1979, the 50-year-old Howell has spent a large part of his career on research to precisely characterize interactions among the fundamental particles that make up the centers of atoms.

Howell's interests have recently expanded to include using gamma rays to measure reaction rates important for simulating nuclear processes that occur in the final life stages of stars, and using radioactive substances to probe how plants respond to increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

He also serves as project manager for a $5.5 million upgrade at Duke's Free-Electron Laser Laboratory, which is collaborating with TUNL to produce increasingly energetic and intense gamma ray and laser beams for use by a variety of researchers.

"What I want to do as TUNL's director is attract the best possible scientists to the consortium," he said. "We have a tremendous group here now -- scientists who are creative, energetic and forward-thinking, and who use technology innovatively to squeeze answers out of nature."

Seventeen faculty from Duke, North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill now work alongside several dozen graduate students and nonfaculty research scientists at TUNL to study a variety of aspects of nuclear physics.

One of Howell's key goals for TUNL is to expand research aimed at deducing the mass of the neutrino, a ghostly subatomic particle that is produced by stellar processes and exploding stars and may also account for some of the "missing" matter astronomers hypothesize is present in the universe but cannot see with telescopes.

With TUNL already well known as a nurturer of young Ph.D.s -- Howell being one of more than 230 examples -- another of his goals is to expand the facility's role in undergraduate physics research and education. In recent years, he has served as the Duke physics department's director of undergraduate studies.

Howell traces his own technological bent to growing up in modest means as one of five children on a farm near South Hill, Va. "By the time we were 13, most of us kids had to have learned to fix anything with a motor, because we simply couldn't afford to put things in the shop," he said.

"Our father was not highly educated, but he had a high mechanical aptitude," he added. "He always felt that if you observed someone doing something once or twice, then you should be able to do it yourself."

Howell credits his devotion to scholarship to his mother, who attended a small college in Lawrenceville, Va., and did substitute teaching in addition to homemaking. "She always emphasized excellence in school," he said. "She didn't micromanage our choices, though. She let us explore what we wanted."

One of his brothers also went on to become a Ph.D. physicist, and a sister obtained a bachelor's degree in physics.

In high school, Howell took every science and math course offered. He won a scholarship to Davidson College, where he struggled over whether to go to graduate school in physics or engineering.

A key factor that headed him toward physics was a visit to Davidson by Horst Meyer, the former Fritz London Professor of Physics at Duke. After viewing Howell's work there, Meyer returned to Duke and mailed to Howell the crucial superconducting wire he needed to complete a physics experiment.

He was further lured to Duke and to TUNL during the scouting trip he made to several graduate schools. "Every professor at Duke stopped what they were doing and took a few minutes to talk to me about their research," he said. "That didn't happen at any of the other schools."

In addition to pursuing answers to some of physics' thorny enigmas, Howell has maintained a steadfast commitment to recruiting minorities into science. He is chair of the American Physical Society's Committee on Minorities in Physics, a member of the National Society of Black Physicists and an adjunct physics professor at North Carolina Central University, and he previously served as faculty coordinator of the Mellon Minority Undergraduate Fellowship program at Duke.

Throughout his experience, he has pondered what he calls a "complex question": why have so few African-Americans like himself become physicists?

"An American Institute of Physics study three years ago found there is a significant correlation between early good performance in mathematics and later success in physics," Howell said.

"In the coming years, I plan to work with local school districts and community organizations to increase the numbers of black and Hispanic students who take the most advanced mathematics courses in high school," he said.