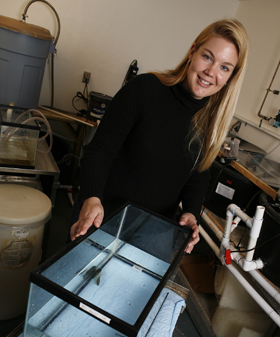

The conveniences of modern life also bring hazards. Heather Stapleton, assistant professor of environmental sciences and policy at the NicholasSchool, is exploring what happens when chemicals used to prevent fires in common household products get into rivers, lakes and other water systems. Like other NicholasSchool faculty, Stapleton's scholarship is intended to lead to better policy and promote public understanding of complex environmental questions.

Q. Your research attempts to trace what happens to organic components when they enter water. What drew you to this field and what do you think you can add to the knowledge in the field?

Heather Stapleton: I grew up wanting to be the classical "marine biologist" and therefore enrolled in a marine science program in college. A few of my classes involved research cruises and sampling in bays and estuaries. As I became familiar with these ecoystems I started to observe the effects of contamination and pollution on water quality and the organisms that inhabited these waters. These experiences led me to enter a graduate program in which I was able to pursue my interest in the transport and fate of organic contaminants in aquatic systems and focus on the bioaccumulation of these contaminants in food webs.

The goal of my research is to help determine the underlying factors influencing exposure and accumulation of contaminants in aquatic organisms. My current research has been investigating the transformation of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in fish. BFRs are chemicals added to products, such as furniture, carpet padding, TVs and other electronic goods, to protect them from fire. However, these chemicals are getting out into the environment and contaminating our aquatic ecosystems. Some fish have the ability to metabolize these contaminants into compounds that are potentially more toxic. My research is attempting to identify these products and understand their long-term fate in the environment.

Q. What are the implications of your research for human health?

HS: Unfortunately, people are exposed to BFRs just as fish are. In fact, studies investigating levels of BFRs in human milk and serum have shown that the U.S. population has the highest levels of these contaminants in the world, most likely because these chemicals are found in products we use every day. From these fish studies we can begin to examine how these contaminants are metabolized by fish and determine if the same mechanisms are occurring in people. These studies will help us to understand the human health issues related to exposure from these compounds.

Q. Why is the NicholasSchool and Duke a good fit for you to do this kind of research?

HS: Duke has some of the best experts and facilities in the world for conducting environmental research. My work often crosses disciplines and can encompass aspects of both toxicology and environmental policy, particularly since BFRs are currently under intense scrutiny and risk assessment. The NicholasSchool is a center for leading studies on wetlands research, endangered species, global warming, toxicology and environmental policy. Great research and science is often a result of great collaborations, and the NicholasSchool offers the best place for bringing together great minds.