From Turkey, On Film

Duke explores Turkey's growing importance in art, politics

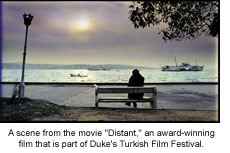

Turkey is the giant nobody notices. Straddling the Bosphorus between Asia and Europe, Turkey has never caught much attention in Western academic circles. Now, a Turkish film festival running until Oct. 22 at Duke -- and a growing interest in Turkish studies on campus -- is beginning to change that.

The festival comes a year after a Turkish film won two awards at the Cannes Film Festival (Grand Prix and Best Performance by an Actor) -- the first Turkish film to win at Cannes in more than two decades. At the same time, political relations between Turkey and the West are about to change as the country enters discussions that could lead to it joining the European Union.

The festival, which has already attracted hundreds of viewers, also aims to bolster Turkish studies at Duke; the country is increasingly featured in Duke course offerings, graduate programs, research publications and study-abroad opportunities.

"The emergence of a new Turkish cinema is an exciting development for all of us," Duke literature professor Fredric Jameson said at a panel discussion that was part of the festival. Jameson compared films in the festival to works by renowned international directors Andrei Tarkovsky from Russia, Michelangelo Antonioni from Italy and Abbas Kiarostami from Iran.

"Some of the films shown in the series are phenomenal," wrote Duke literature professor Negar Mottahedeh, who organized last year's controversial "Reel Evil" series that featured films from Iran, Iraq and North Korea. "They are stimulating in their visual representations and in the stories they tell."

Although the films are mostly set in Turkey with Turkish actors and dialogue with English subtitles, many of their themes are universal dramatic material. In his presentation, Jameson said the films dealt with issues such as humanity's relationship to nature in a society changing from a peasant economy to a capitalist industrial one, struggles with loneliness in modern urban life, and the pervasiveness of media images.

Turkish filmmaker Zeki Demirkubuz, who has four films in the festival, spoke at the campus discussion. Through his translator, he said he doesn't consider himself "a Turkish director," and joked that, "My filmmaker-side is something that I live just like a hired killer" -- unconstrained by national boundaries.

One overarching theme in the movies inspired the name of the festival: "Arada," Turkish for "Between." Festival co-organizer Erdag G¶knar, a Duke professor of Turkish language and literature, said the name is apt for geographical, social and political reasons.

Turkey lies between Europe and the Middle East, the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, Central Asia and Eruope, said G¶knar, an American who has spent many years living, studying and visiting family in Turkey. Also, he said, the country found itself between cultures after undergoing a government program in the 1920s and '30s to modernize and secularize after the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

"So there's a sense that in doing that so rapidly that it somehow led to a crisis, a dilemma of identification -- Are we Eastern? Are we Western?" he said. "Any book that you pick up on Turkey will touch upon this theme. It's true to a certain extent, but it's also a cliche."

Another festival co-organizer Professor G¼ven G¼zeldere, gave an example of how he sees Turkey's history influencing the films. G¼zeldere grew up in Turkey and lived through the country's military coup in 1980, a time he remembers as being characterized by power struggles and betrayal.

"In many ways the themes of injustice and betrayal [became] very much parts of people's everyday lives during that very difficult period," he said. "So when I look at a Demirkubuz film [dealing with betrayal], even if there's nothing explicitly political, I see, implicitly, a very strong political undercurrent."

In addition to focusing attention on Turkish culture and history, the "Arada/Between" series aims to promote Turkish studies at Duke, an area of study that has been gradually expanding at the university over the last decade.

Duke has no specific Turkish studies program, but G¶knar and others said a consortium of faculty have proposed a new Ph.D. program in Slavic and Eurasian studies, which would include study of Turkish and Turkey.

Bruce Kuniholm, a Duke professor of public policy and history, has long championed the study of Turkey, a country in which he spent some of his childhood, then later studied, taught and played professional basketball there. (He insisted his basketball stint was a modest achievement given the level of play in Turkey in the '60s.)

"It was clear in the post-Cold War era that Turkey was playing an increasingly important role" in world politics, he said. And yet study of the country always received "short shrift" because it didn't quite fit into a major area studies programs for Europe, the Middle East or Asia.

As Duke's vice provost for international studies from 1996 to 2001, Kuniholm initiated a faculty exchange with Ko§ University in Istanbul that lasted until 2002; it was funded by the Fulbright Foundation and included an American film festival in Istanbul. He was also able to get a Turkish language instructor hired at Duke, through a joint effort with Trinity College dean Bob Thompson and Professor Edna Andrews, chair of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature and director of Duke's Center for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies.

Turkish studies are growing at Duke in other ways. A new study abroad program in Istanbul begins next summer; and the library is now systematically collecting Turkish films and books. Next year, a FOCUS program on the Middle East will include material on Turkey, and last year, an issue of the academic journal The South Atlantic Quarterly, co-edited by Duke's G¼zeldere and Professor Sibel Irzik of Bogazici University in Istanbul, and published by Duke Press, focused on Turkey, including articles from four Duke professors.