The Mystery of Ishi's Brain

Orin Starn explores what the story of the last Yahi tribesman means for us today

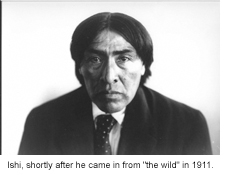

After years of living in the hills and hiding from whites, a Native American man emerged from the wilderness of Northern California in August 1911. He was emaciated and starving and could no longer survive on his own.

Often called America's "last wild Indian," he was the sole remaining member of his Yahi tribe. He was turned over to the care of renowned anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, who called him "Ishi," an approximation of the word "man" in the Yahi dialect. Ishi spent the last five years of his life in a San Francisco museum, where he was the subject of study and a living exhibit for weekend visitors.

Like many children growing up in California, Duke cultural anthropologist Orin Starn was fascinated by the story of Ishi. In the years after his death, Ishi had become a mythical figure -- because of, in part, the best-selling book, Ishi in Two Worlds by Kroeber's wife.

"I had this image of Ishi as the untouched Native American in a hideout," Starn said. "He lived in the hills and made fire with sticks."

Starn returned to the story of Ishi as an adult, seeking to cut through the mythology that surrounded him. The result is his version of the story, Ishi's Brain: In Search of America's Last 'Wild' Indian (W.W. Norton & Company).

Starn will talk about the book Sunday, Sept. 26, at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV's literary series North Carolina Bookwatch with host D.G. Martin.

Early in his research, Starn stumbled upon a mystery: What had happened to Ishi's brain?

"At one level, it's a detective story," he said. "It's also a personal story about my research to find out what happened."

Despite Ishi's stated wishes to the contrary before his death, anthropologists did an autopsy of Ishi after he died. His body was then cremated and placed in a pot in a cemetery. But an Indian activist seeking the return of Ishi's remains told Starn that the brain had been removed, pickled and sent to the Smithsonian.

Starn launched a cross-country search for the brain, which he finally located in a Smithsonian warehouse in Maryland. The brain eventually was returned to the Pit River tribe in Northern California, who buried it along with Ishi's ashes.

Using the unfolding mystery of the brain as a framework, Starn addresses in his book the genocide of Native Americans, the history of anthropology and provides a picture of Native California today.

In writing the book, Starn said he tried to present an honest account of events that are often highly charged. As a symbol of the destruction of native people, Ishi's story had become so weighted with significance that it was difficult to peel away the legends and tell the story of the real Ishi, he said.

The book, which is written in the first person, also recounts Starn's own internal conflict as a white anthropologist studying Native American issues.

Knowing the role that anthropologists had played in the removal of the brain made the moment when he actually saw it especially wrenching, he said.

"It was a graphic, jarring sight," he said. "It was an extremely emotional moment.

"On the one hand Ishi was befriended by white anthropologists and scientists and at the same time they viewed him as a specimen and ultimately treated his body in a way that was very against Yahi beliefs."

In the end, however, Starn said he was glad to have played a role in the return of Ishi's body, which was buried in a secret location in 2000.

"Ishis's story is such an important one," he said.