Music and Civil War in Zimbabwe

A mbira scholar uses an unusual theater piece to pay tribute to musicians silenced by a decade of violence in Zimbabwe

The song was woven with threads of African and Spanish melodies, and it took a careful ear to discern the English words in the foreign music.

"The blacksmith's forge lies silent, hammer's turned to rust," sang Paul Berliner from the Sheafer Theater stage, his voice expressing melancholy. "Mbira that gladdened a thousand hearts, gone missing."

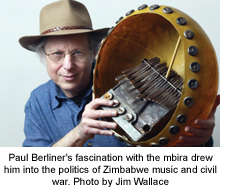

As accompaniment, he played the mbira, a hollowed gourd instrument from Zimbabwe with a set of keys inside that resemble neatly aligned spoon ends.

He sang of the desolation of a Zimbabwean village during a time of civil war, the ruination of nature and the loss of life and music.

"The ax forgets, but the tree remembers," the song ended.

Berliner's was performing in January a one-man show, a 75-minute theatrical piece titled "A Library in Flames: A Story of Musicians in a Time of War," co-sponsored by the Duke Institute of the Arts and the John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies as part of the institute's year-long series, "The Arts in Times of War."

Berliner, a visiting professor of ethnomusicology from Northwestern University, recreated the story of his experiences with the mbira in Zimbabwe, and the particular cultural and political moment of turmoil there that engulfed many of his friends and musical mentors.

Berliner came to Duke this year as a research fellow at the Franklin Center to work on several projects, including a sequel to his first book about Zimbabwe, The Soul of Mbira, published in 1978. The sequel accounts of the mbira artists' wartime experiences collected after Zimbabwe's independence, including material too dangerous to publish at the time of the first book.

Berliner first became interested in mbira in 1967, when he discovered the instrument by chance in an import store.

"I was fascinated by this instrument with such unique melodic qualities, so different from the Western stereotype of African music as drumming," Berliner said. "It also had an unusual buzzy quality produced by shells and bottle tops that functioned like the snares on a snare drum, a pure tone but with a buzz, like a snare."

Berliner left the U.S. in 1971 to study mbira in Zimbabwe only to find the country was beginning a decade of violent turmoil. It started with a revolution overturning decades of white majority rule, which was followed by a protracted and bitter civil war between the two major parties that emerged after the revolution.

Much of Berliner's one-man show is about how musicians were inevitably drawn into the conflict. Zimbabwe was, he said, a place "where music, politics and religion constantly overlapped and interacted with one another."

With a blend of slides, music, and spoken words in his performance, Berliner depicted the faces and fates of prominent mbira performers -- several with whom Berliner studied -- who had been terrorized or even killed in the violence. The title of the piece comes from one slide where he uses an image of a library in flames to represent the loss of knowledge and the implications of civil struggles, he said.

After coming to Duke, Berliner was invited by Kathy Silbiger, Institute of the Arts director, to present "A Library in Flames" as part of the "The Arts in Times of War." While at Duke, he met Jeffrey Storer of Duke's theater studies department and the local Manbites Dog Theater. The two collaborated to translate Berliner's research and experiences into the theater piece.

"Theater, when it's at its best, tells stories that might otherwise be lost, and hopefully in a way that captivates the audience," said Storer. "I came to the experience with no knowledge of Paul, the instrument, and the role of the instrument in the culture and politics, but what I had to offer to the process was a history of telling stories in the theater."

Storer worked with Berliner to write a script, plan the stage setup, the music being played, and the timing. He acted as a coach for Berliner as well, helping him to become more comfortable with solo performance.

"Paul allowed his own body and voice to be a medium for the story," said Storer. "He remembered the conflict and the voices for us."

But the political and cultural conflicts were only two layers of a complex performance, said Storer.

The premise of friendships across cultures, and the divide and death that war created between many in the musical brotherhood, was played out several times in Berliner's monologue.

"In both the content and in the tone of the piece, Berliner's profound sense of personal commitment to the community of artists and his friendship with them wer evident," said Daniel Hoffman, a graduate student who attended the performance. Hoffman said he was struck by Berliner's personal narratives of apprenticeship and later searches for lost teachers.

"With live performances of this shared musical experience woven into the visual archive, it was impossible to experience this as detached or impersonal research," said Hoffman.

Storer and Berliner described the universality of the piece as well.

"Flames" embodies anti-war sentiments and calls for peaceful solutions to social conflicts, Berliner said, as he spoke about the huge toll Zimbabwe's liberation struggle took on civilians caught between warring guerrilla factions.

"Especially today, with the war in Iraq, it reminds you of the powers that are unleashed in war that you just can't control," said Berliner. The work is an attempt to humanize the situation and show the plight befalling individuals caught among conflicting pressures, he said.

Several attendees spoke of the power of the piece.

"Art is a political act," said Storer. "When you take control of framing a story, it can be a powerful thing."

Written by Pushpa Raja, a Duke junior.