Identity Crisis

Keeping personal data at Duke safe in the new digital age

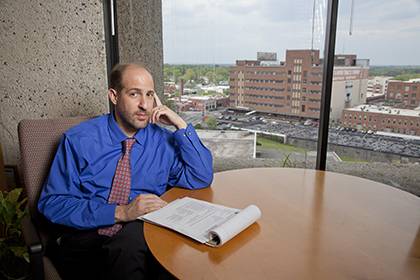

The email looked like many of the several hundred messages that arrive in Hayden Bosworth's Duke inbox on any given day.

When he clicked on the link to "confirm your login details" for his NetID, the website he arrived at - like the email - looked legitimate.

"Everything looked like it was from Duke," said Bosworth, a professor of medicine, psychiatry and nursing who has worked at Duke since 1997.

He didn't think anything of entering his Duke NetID and password that November day last year. Two months later, he'd just returned to campus after spending the winter holidays in Florida with his family when he got a call from Duke Financial Services asking if he had changed the bank account where his paycheck was deposited?

He had not, but someone else had. Bosworth's December paycheck had been rerouted to an unauthorized account in an Internet phishing scam that targeted many universities late last year.

Duke officials soon learned that in addition to Bosworth three other Duke employees' direct pay was redirected after the employees entered their NetID and password in the fake website that looked like Duke's standard login page.

Since the attack, Duke has worked with those affected and with external agencies to implement new security features to protect personal data, including payroll transactions on the Duke@Work self-service website. But as phishing attacks grow increasingly common and sophisticated, IT security experts warn that everyone at Duke must take individual action to prevent data breaches.

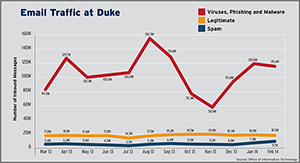

Keeping your data private is vital considering the increase in email attacks. Of 180 million emails sent to Duke users last August, less than 10 percent were legitimate; 3 percent were spam and 87 percent were viruses, phishing and malware. That’s more than 156 million malicious messages during the month. Most of these emails were intercepted by Duke's IT Security systems before ever reaching the user, but identifying these messages is a constant challenge.

"These attacks will only get worse," said Richard Biever, the university's chief information security officer. "Never send your password or sensitive information in response to an email. Duke will never request your NetID password or other authentication information by email or phone."

None of Duke's information security systems have been directly hacked through the phishing incidents, and the employees got their pay replaced. But since the direct deposit incident, Duke now recommends that all faculty and staff enroll in and use multi-factor authentication, which provides an additional layer of security when logging in or performing transactions online.

"If you choose not to use this security tool and submit your network identification and password as the result of a phishing attack, Duke cannot guarantee the replacement of any funds that may be lost as a result," Tallman Trask III, executive vice president, wrote in an email to all employees in March.

Working together in a crisis

Earlier this year, Duke Corporate Payroll Services served on the front lines of the direct deposit response, helping the employees whose pay was stolen.

Anne L. Comilloni, director of operations for Duke Corporate Payroll Services, and others in her office worked until 11 p.m. that January night, calling Duke staff and faculty whose accounts showed direct deposit changes to banks her staff didn't recognize. She was part of the team that implemented new security measures to protect Duke users.

"Hackers targeted the School of Medicine, where many of our folks are so busy with patient care, they're just clicking," she said. "And the rerouting of direct deposits came at the worst time, at the holidays when a lot of people were away and not looking at their bank accounts."

Dan Blazer II, an endowed professor of psychiatry at Duke, was among the employees Comilloni’s team called to help after his pay was rerouted.

"In my 40 years at Duke, the check was always deposited in the same bank," Blazer said. "Realizing that this happened means it could happen again. It definitely makes me more cautious about what I do."

After the theft, Blazer signed up to use the multi-factor service with his office phone, where he now receives an auto-generated call every time he logs in to the Duke@Work self-service website. When logging in with multi-factor, a user is required to enter a password and also authenticate using a second factor, typically a phone or hardware token that generates a random passcode.

"It's worked without a problem, and I'm so happy they're doing it," Blazer said. "It's a scary time, when you think about how sophisticated the phishing attempts are becoming. Staying a step ahead is no easy task. I appreciate Duke changing the system."

More than 4,000 Duke faculty and staff have enrolled in the multi-factor service to date.

Higher education a target

Criminals can glean whatever information is publicly available online to tailor phishing attacks to individual victims, said Thomas Hyslip, a Raleigh-based U.S. Department of Defense agent who manages the cybercrime unit. Universities face an even tougher challenge in securing their systems because of the open intellectual environment valued in academia.

"Historically, the Internet was designed to be wide open so researchers could share information easily. In a university setting, academics want to be able to collaborate with others in the field. But on the Internet now, every criminal organization is trying to steal information, and you just don't know who you're talking to," Hyslip said. "Do you share your pin number for your ATM card? That's what you're doing when you give out your password."

Higher education is likely to become an even bigger target, Hyslip said.

"Universities are where much of the cutting-edge technologies are being developed. Government and other industries like banking are locking down, and as they do, criminals will go to the low-hanging fruit and easiest targets. I would predict higher ed will see a bigger proportion of attacks down the road, especially if they don't increase security."

Security experts at Duke are coordinating closely to implement new procedures to identify potential compromised NetIDs so accounts can be protected quickly.

"Even with all the system protections, passwords are the single biggest source of risk," said Chuck Kesler, chief information security officer for Duke Medicine. "All it takes is a single password to be compromised for a data breach to happen. There are a lot of nefarious characters out there who are trying to take advantage of Duke people. Like a community watch, everyone has a role to play in security. We can’t do it by ourselves."

A painful lesson

Danielle Mee, a clinical trial coordinator with the Duke Clinical Research Institute, learned the hard way after clicking on an email link that came into her Duke account to enroll in what she thought was a Duke-affiliated paycheck-advance service.

"At the hospital where I worked before, you could get a payday advance. This seemed like an answer to a prayer," she said. Instead, though, she ended up signing up for three online payday loan services. She's still paying off the balances and receives dozens of phishing emails each week.

"It's a hard and painful lesson to learn, but I won't do it again," Mee said. "Now I delete those emails without opening them."

Malicious emails are not always financially focused, but they can still create plenty of disruption.

Khristen Dial, assistant director of external affairs for Duke Athletics, received an email last summer that appeared to be from Duke. It warned that her email account had reached its storage limit. Dial clicked a link "to increase your storage capacity" and launched a computer virus.

"Once I clicked that link, it opened up Pandora's box," she said. "My computer had to be fully wiped clean of everything, so I lost a lot of my documents and files I'd been working on. It was so frustrating. From that experience, I definitely learned to monitor emails I get and what I click on. Now, any time I have a question, I always ask our director of IT before I do anything. If you think it's something not legit, if anything raises an eyebrow, ask before you click."

William Falls Jr., a staff specialist in the business office at the School of Nursing, advocates healthy skepticism. Faculty and staff members in the School of Nursing were among those targeted with the scam email earlier this year in the rerouting of direct pay.

"I never click on links in emails, especially those that say, 'Click here to log in.' I close the email and go directly to the site myself to log in," Falls said.

Sometimes it takes a serious incident like a rerouted paycheck to really raise awareness, said Bosworth, the professor of medicine, psychiatry and nursing whose pay was rerouted.

"I was hesitant to share my story, but then I thought: It's worth it if someone out there can learn from this," Bosworth said. "People may complain about the lack of convenience that comes with increased security, but the alternative is not getting your December paycheck and worrying how you're going to pay your credit card bills."