Researchers have identified the set of tools an infectious microbe uses to persuade a plant to open the windows and let the bug and all of its friends inside.

The microbe is Pseudomonas syringae, a successful bacterial pathogen that produces characteristic brown spots in more than 50 different species of plant. The signal it uses is a molecule called coronatine, which to the plant looks just like its own jasmonic acid, a signal that is part of the plant's immune system. The pathogen "hijacks" a system that balances the plant's two different defense strategies, said Xinnian Dong, a Duke professor of biology.

Plant pathogens have two basic strategies, Dong said. One approach kills cells and harvests what's left of them for food. The other is more like parasitism, setting up housekeeping in and around living cells and using what they provide. So the plant has two kinds of defenses. Against necrotrophs, the cell-killers, the plant produces jasmonic acid and does what it can to keep cells alive. Faced with biotrophs, the parasitic type, it tries to kill the infected cells. These responses work in opposition to one another and through cross-talk to keep the plant carefully calibrated, depending on the pathogens it encounters.

"Breaking the cross-talk between the systems would be a problem because the plant may respond the wrong way," said Dong, who is also a research fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF). "Pseudomonas is successful by hijacking a critical process in this cross-talk."

"It's all connected," said graduate student Xiao-yu Zheng, who worked on the project for four years. "That's the beauty of it." Zheng is the first author on an article appearing in the June 14 edition of Cell Host & Microbe. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy.

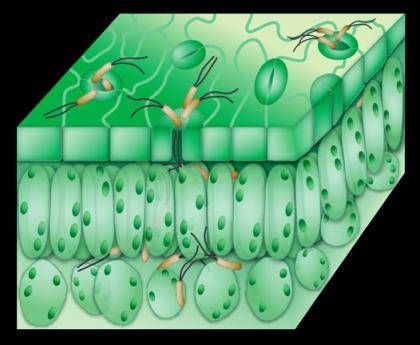

Pseudomonas is a biotroph, the parasitic kind of attacker. But the coronatine it produces touches off a cascade of molecular activity that mimics a necrotrophic pathogen invasion. The plant responds to coronatine with three transcription factors that work together to lower the plant's supply of salicylic acid and keep the infected cell alive. Normally, salicylic acid is involved in closing the stomata and an essential signal for the cell-killing defense that would be most effective against a biotroph. So by jamming that signal, pseudomonas keeps the stomata open for more bacteria to invade, and it has free reign to reproduce in the spaces between cells.

In this arms race, the plant can't just abandon its stomata. The openings are essential for exchanging gases and water vapor and the plant adjusts them constantly in response to CO2 concentrations, humidity, sunlight and other environmental factors.

At least being able to shut the stomata is a good first line of defense for many plants, explains Maeli Melotto, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Texas - Arlington, who originally discovered pseudomonas opening the stomata. "This study elegantly adds extremely important pieces to the big puzzle of how coronatine works inside the plant cell," said Melotto, who was not involved in the current study. "Coronatine contributes to disease progression in virtually all stages of the disease," giving scientists a good way to understand the full process of bacterial pathogenesis.

For now, the Duke finding is specific to the well-studied mustard plant Arabidopsis, but it should be possible to identify and test similar transcription factors in other plant species that are manipulated by pseudomonas, Zheng said.

CITATION: "Coronatine Promotes Pseudomonas syringae Virulence in Plants by Activating a Signaling Cascade that Inhibits Salicylic Acid Accumulation," Xiao-yu Zheng Natalie Weaver Spivey, et al. Cell Host & Microbe, June 14, 2012. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.014