Durham’s Black History Is a Large Part of Durham History

Consider: On Nov. 7, 1898, a white supremacist political campaign led by wealthy white men across North Carolina reached a violent flash point in Wilmington, where a vigilante group led a coup d’état of the local multi-racial government that forever reshaped the trajectory of the state.

By comparison, on Aug. 22, months before racial terrorism in Wilmington, a group of Black leaders in Durham, including businessman John Merrick; Aaron McDuffie Moore, Durham’s first Black physician; and pharmacist and North Carolina Central University founder James E. Shepard, met at Moore’s office and began a new venture, a Black-run insurance company benefiting Black policyholders – North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company.

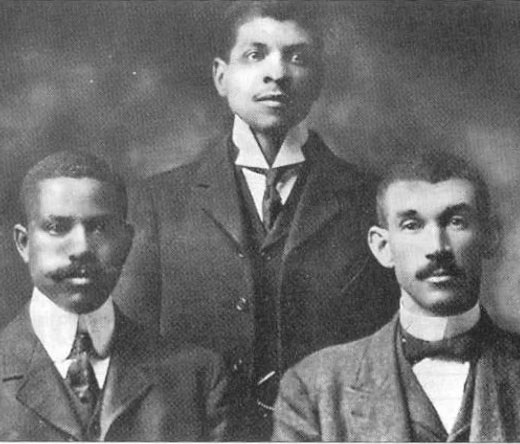

Merrick and Moore were later joined by Charles C. Spaulding; the three men – known as the “Triumvirate” – would build the largest African American insurance company in the world before closing in 2022.

In honor of Black History Month, Duke celebrates African Americans’ distinctive achievements in Durham. While Duke has had an uneven history with the Black community, as DuBois noted, the community’s remarkable achievements were realized in concert with the Duke family and growth of the university.

A relationship with long ties

Duke’s relationship with Durham’s Black community dates to Trinity College’s move from Randolph County to Durham in 1892, one year after the construction of the St. Joseph’s AME Church in the city’s historically Black Hayti District.

The “Mutual” was the economic engine that powered Durham’s Black Wall Street, and Hayti garnered praise from Booker T. Washington and DuBois, who rarely agreed on anything.

During a post-Reconstruction era when Southern Democrats preached the virtues of white “Redemption,” the Washington Duke family were staunch Republicans. They were derided as scalawags and race traitors because of open alliances with Black leaders such as Merrick and Moore, Blake Hill-Saya wrote in a biography of Moore.

That live-and-let live policy served both parties’ interests. Washington Duke and his sons counted on Black workers’ labor in their factories, and Black entrepreneurs could focus on developing their enterprises without racial antagonism, noted Hill-Saya.

Washington Duke and the Black community

Merrick, the son of a formerly enslaved woman and white man, was key because of his position as Washington Duke’s barber. Before co-founding N.C. Mutual, Merrick opened his first barbershop on March 6, 1892, and over the decade he opened four more shops: three for whites and two for Blacks.

Merrick’s ambition was his own, but Washington Duke likely encouraged “Merrick in whatever ideas he conceived, perhaps giving him practical advice on how to put them into action,” wrote Jean Bradley Anderson in “Durham County.”

The Duke family and university’s contributions to Durham’s most venerable Black institutions, particularly in the Hayti District, have had a lasting impact.

In 1868, three years after the Civil War, the formerly enslaved Edian Markham, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) missionary, moved to Durham and helped establish St. Joseph’s AME church on a parcel of land that is the present-day site of the Hayti Heritage Center.

In 1890, a community fund-raising campaign to build a new church welcomed donations from the white community. Washington Duke made contributions to the church and likely commissioned for its construction the architect, Samuel Leary.

The cornerstone of the church was laid in 1891, and its leaders honored Washington Duke, whose image adorns a stained-glass window in the sanctuary’s balcony.

Hayti’s very name is an open acknowledgement and admiration of Haiti, the Caribbean country that won its independence in 1804, and became the first republic in the Western Hemisphere. The church leaders placed a Haitian “veve,” a symbol of love and protection atop of the steeple, instead of the traditional Christian cross.

In 1901, three years after the Wilmington race massacre and the start of N.C. Mutual, the Lincoln Hospital was co-founded by Moore, Merrick and Stanford L. Warren, Durham’s second Black physician.

The three men persuaded Washington Duke that a hospital “would be a more valuable investment than Duke's idea of building a monument on the Trinity campus to honor African Americans who had fought for the confederacy,” according to the Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives.

Duke paid for the hospital’s construction costs and provided an initial $5,000 endowment.

The tangible evidence of racial interdependence between Duke and the Black community continued throughout the decades.

In 1937, the former North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) built a new auditorium and named it in honor of Benjamin Duke, in recognition of his financial support.

An agreement that more work is needed

Duke’s relationship with the city’s Black community has had its low points, including a long struggle to enroll Black students, hire Black faculty and offer equal opportunity for Black employees.

In 2021, Mark Anthony Neal, the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African and American Studies, said that Duke “has long had the reputation of being “the place they go to work, and where they might in fact feel undervalued and underpaid.”

During Duke’s Centennial, that history was acknowledged, including an agreement that more work is needed. Duke held a dedication ceremony to rename the East Campus Union the George and George-Frank Wall to honor two longtime custodians, George Wall, an early employee, and his son, George-Frank Wall.

In addition, Duke has also worked closely with the restoration efforts of the Pauli Murray Center for History and Justice, housed in Pauli Murray’s childhood home in West Durham. Murray was a legal scholar whose 1944 law school thesis was cited in Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s arguments in Brown v. Board of Education – the landmark Supreme Court case that found racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

Jesse Huddleston chairs the board of the Murray Center. A 2010 Duke graduate, Huddleston works as a senior program coordinator in Duke Community Affairs, organizing alongside community leaders involved in the Duke-Durham Neighborhood Partnership.

Huddleston said Murray’s childhood home in Durham’s West End was built in 1898 by the eminent scholar’s maternal grandparents. Her grandfather Robert Fitzgerald was an educator, and his brother Richard owned a brick manufacturing business whose inventory built many structures throughout the city, including St. Joseph’s AME Church.

In the late 2000s, a group of West End residents, friends and local advocates formed the Pauli Murray Project with the dual goals of uplifting Murray’s legacy and preserving their childhood home.

Huddleston said several of the advocates worked at Duke and leveraged their relationships with the university to gain more support for the project.

It worked.

In 2016, “Duke seeded money to the Self-Help Credit Union to start a land bank in the West End, and Pauli Murray’s home was part of that land bank,” said Huddleston, who added the land bank ensured parcels of land “would not be snatched up by private developers and allowed community members to have a seat at the table.

“If it were not for the land bank the community would not have had the wins we’ve had at the Pauli Murray Center,” Huddleston said.

The wins include purchasing the Murray site from the land bank this year.

Huddleston said a review of Duke’s relationship with Durham’s Black community is an ongoing effort to “improve outcomes for Black people and the community at-large. ... Duke is well-positioned to continue supporting different initiatives and supporting Black history,” Huddleston said. “We have this shared history, and when Black people are doing better, all people are doing better.”

FOR MORE READING: SOURCES CITED IN THIS STORY

Jean Bradley Anderson, “Durham County: A History of Durham County, North Carolina”

Blake Hill-Saya, “Aaron McDuffie Moore: An African American Physician, Educator, and Founder of Durham's Black Wall Street”

Open Durham, “Hayti Heritage Center/St. Joesph’s AME Church.”

Pauli Murray, “Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family.”