Weather-Changing El Niño Oscillation Is at Least 250 Million Years Old

Modeling experiments show Pacific warm and cold patches persisted even when continents were in different places

"In each experiment, we see active El Niño Southern Oscillation, and it's almost all stronger than what we have now, some way stronger, some slightly stronger," said Shineng Hu, an assistant professor of climate dynamics in Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment.

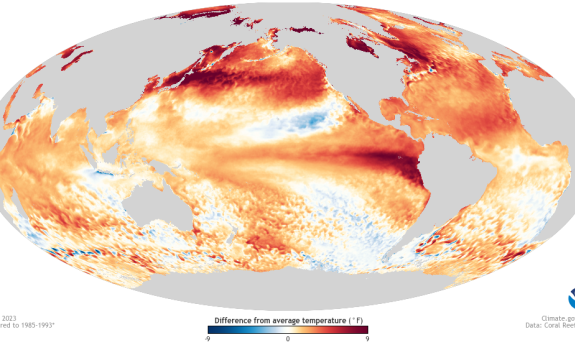

Climate scientists study El Niño, a giant patch of unusually warm water on either side of the equator in the eastern Pacific Ocean, because it can alter the jet stream, drying out the U.S. northwest while soaking the southwest with unusual rains. Its counterpart, the cool blob La Niña, can push the jet stream north, drying out the southwestern U.S., while also causing drought in East Africa and making the monsoon season of South Asia more intense.

The researchers used the same climate modeling tool used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to try to project climate change into the future, except they ran it backwards to see the deep past.

The simulation is so computationally intense that the researchers couldn't model each year continuously from 250 million years ago. Instead they did 10-million-year 'slices' -- 26 of them.

"The model experiments were influenced by different boundary conditions, like different land-sea distribution (with the continents in different places), different solar radiation, different CO2," Hu said. Each simulation ran for thousands of model years for robust results and took months to complete.

“At times in the past, the solar radiation reaching Earth was about 2% lower than it is today, but the planet-warming CO2 was much more abundant, making the atmosphere and oceans way warmer than present," Hu said. In the Mezozoic period, 250 million years ago, South America was the middle part of the supercontinent Pangea, and the oscillation occurred in the Panthalassic Ocean to its west.

“The study shows that the two most important variables in the magnitude of the oscillation historically appear to be the thermal structure of the ocean and "atmospheric noise" of ocean surface winds,” said Xiang Li, a postdoc at Duke, who is the first author.

Previous studies have focused on ocean temperatures mostly, but paid less attention to the surface winds that seem so important in this study, Hu said. "So part of the point of our study is that, besides ocean thermal structure, we need to pay attention to atmospheric noise as well and to understand how those winds are going to change."

Hu likens the oscillation to a pendulum. "Atmospheric noise – the winds – can act just like a random kick to this pendulum," Hu said. "We found both factors to be important when we want to understand why the El Niño was way stronger than what we have now."

"If we want to have a more reliable future projection, we need to understand past climates first," Hu said.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42488201) and the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet (2022-03617). Simulations were conducted at the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

CITATION: "Persistently Active El Niño–Southern Oscillation Since the Mesozoic," Xiang Li, Shineng Hu, Yongyun Hu, Wenju Cai, Yishuai Jin, Zhengyao Lu, Jiaqi Guo, Jiawenjing Lan, Qifan Lin, Shuai Yuan, Jian Zhang, Qiang Wei, Yonggang Liu, Jun Yang, Ji Nie. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Oct. 21, 2024. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2404758121