Looking Back at Duke English in the ’80s

Fish, Tompkins return to share stories of how the department became the center of national attention

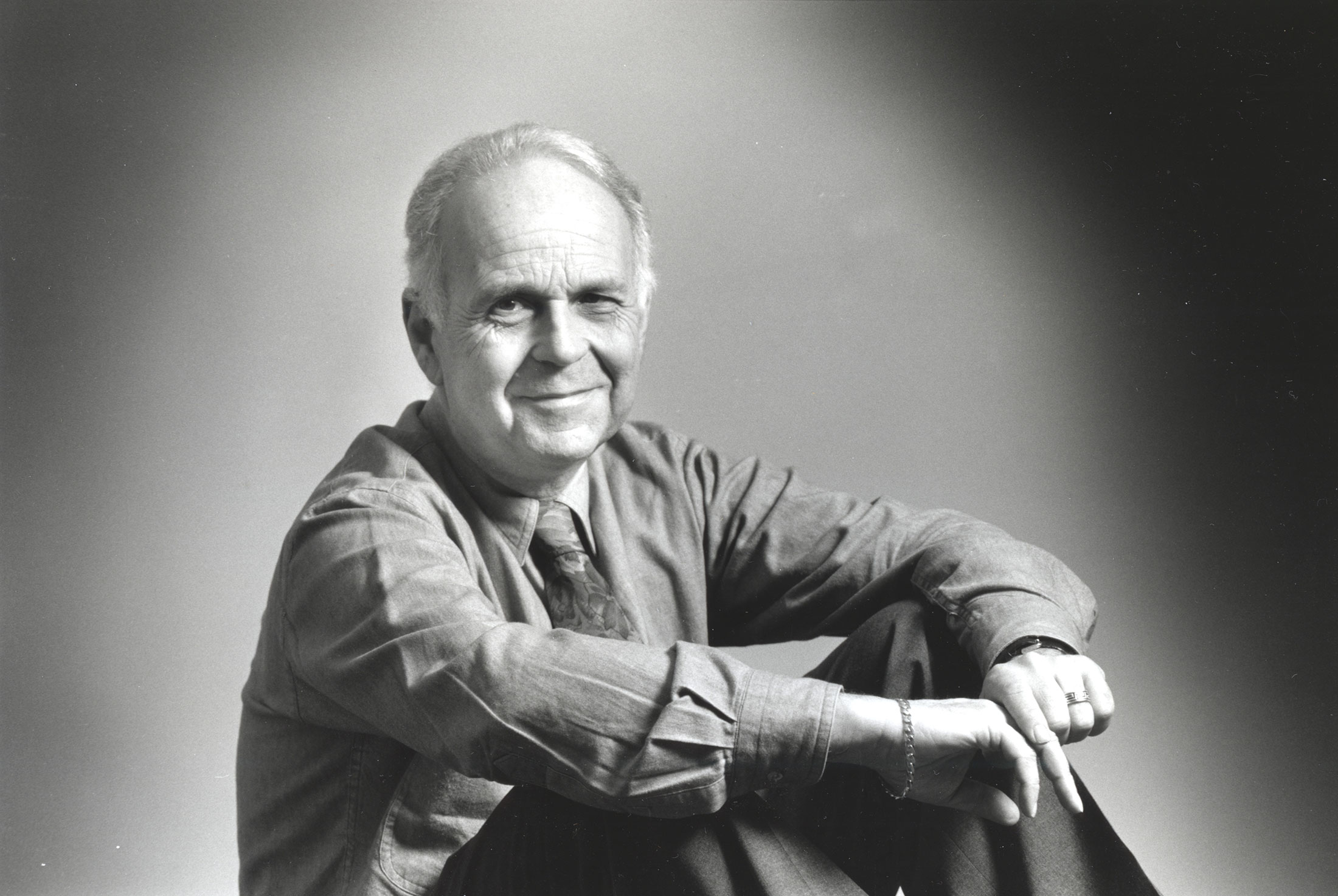

Fish, who was Arts and Sciences Professor of English and Professor of Law at Duke, was intrigued from the start: “I wanted to take a department that was set in its ways and insecure about itself and make it a national center of attention.”

“In the early 1980s, Duke was a good regional school with some special areas of strength, but frankly in arts and sciences, it was short of being distinguished,” said Fish, a noted Milton scholar and an innovator in literary criticism. “The English faculty was populated by men – there were almost no women – who were doing work that was traditional, historical and non-theoretical. There’s nothing wrong with that; I’ve done more than a little bit of it. But in 1985, that wasn’t where the action was.”

Fish said the foundation for change had been laid before he arrived by Frank Lentricchia, a Duke alumnus who had returned to Duke as a faculty member in English and Literature, and who encouraged the hiring of Fish and Tompkins despite opposition from some faculty.

Fish was given funds with which to recruit notable new senior faculty. In the later public controversies, these hirings were often lumped together as theorists, often with a Marxist or deconstructionist focus. Some embraced the brand. But like Fish and Lentricchia, many focused on canonical work, although adapting new approaches that could bring novel meanings and interpretations that challenged long-held ideas.

However, Fish said he knew it would take more than hiring a bevy of academic stars.

FHI 25th Anniversary

This talk was part of a Franklin Humanities Institute series of events during the Centennial year that also marks the 25th anniversary of the institute.

The next event will be held Oct. 18 at 9:30 a.m. in Smith Warehouse. Three Duke English and Literature alumni Mandy Berry, Kathryn Kent and Jonathan Flatley will discuss their scholarship in a conversation on “Queering Duke.”

“Stockpiling stars doesn’t ensure success. You can’t just take academic stars from a cosmopolitan environment and helicopter them into a new environment …. Ways and morés had to change.”

Fish tackled low morale by offering incentives to mid-level faculty to boost their scholarly productivity and securing space for the entire department on the third floor of the Allen Building, where it still resides.

Change went beyond the department. Fish worked to make Duke University Press a leader in the humanities field. In 1999, the Franklin Humanities Institute was founded to strengthen collaboration among humanities faculty.

These efforts brought national attention as well as criticism on campus and in the national press as the Duke English department became a lightning rod for the “culture wars” of the 1990s. A major story in the New York Times heralded the department’s changes bringing theory into the literature classroom, while the Wall Street Journal and Dinesh D’Souza wrote scathing pieces condemning the department.

Today, decades later, Fish appeared bemused by the controversy. For him it was a sidebar to the goal of making Duke one of the drivers of new humanities scholarship.

“No politics follows from theory -- literary or any other. Neither the fears trumpeted by the other side or the hubristic hopes of our faculty were realized, at least as a consequence of what was being done in our classrooms. I think the topic of the politicization of literature was a false issue.”

The change in English was connected to, and strengthened by, other academic departments. Fish, Tompkins and others referred several times to Fredric Jameson, one of the world’s leading literary scholars, who came to Duke in 1985 to direct the Program in Literature. Jameson died last month and was remembered by a moment of silence at the event.

“As a chair he was most rigorous,” Fish recalled of Jameson. “He wanted a program where students were simultaneously trained in the most traditional and honor-bound ways but also were free to explore new avenues of study wherever they emerged. His joyous and expansive personality helped make it possible.”

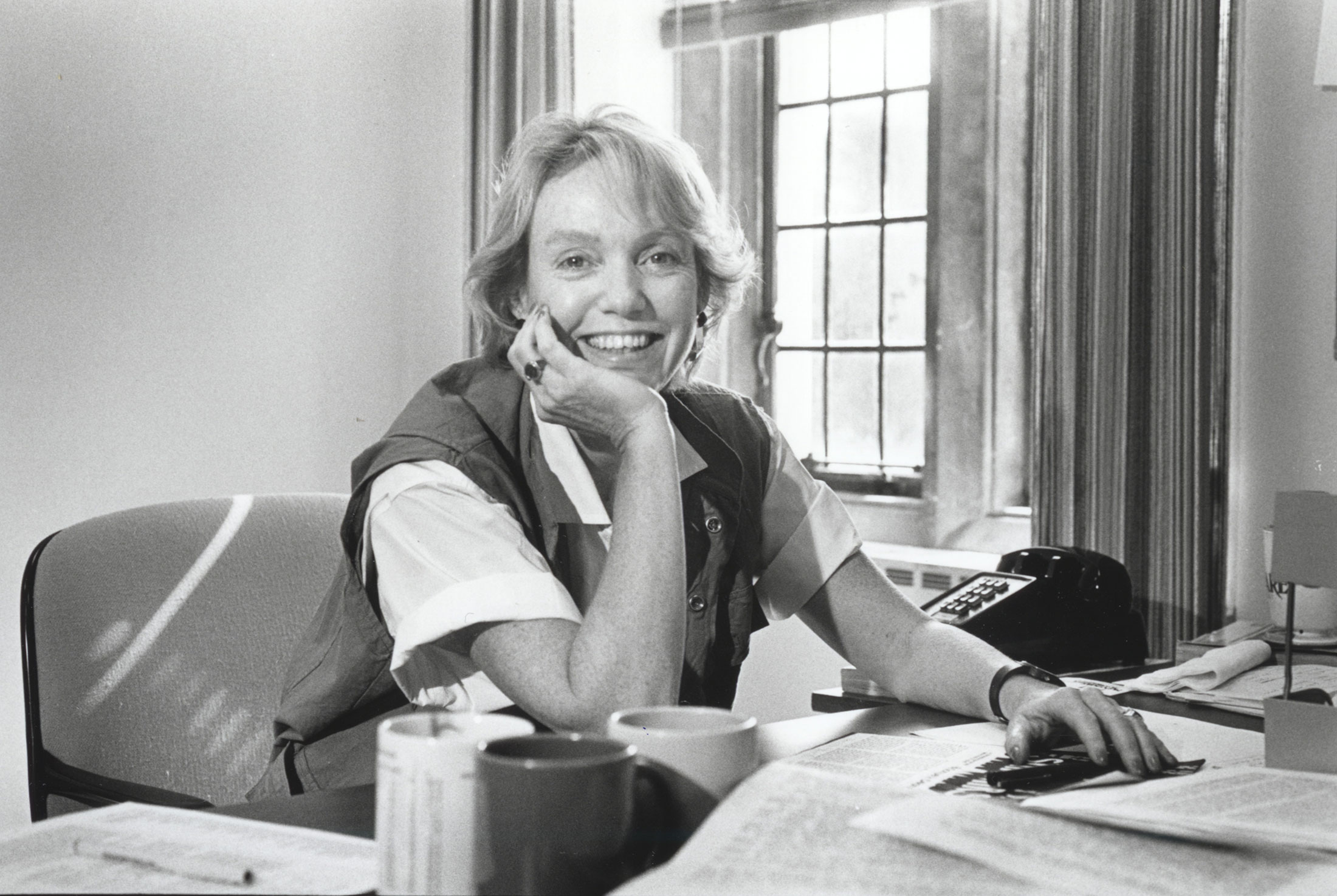

Cited in the New York Times story as “the crown jewel of the department,” Tompkins came to Duke reluctantly after an inauspicious first visit. On her second trip she was met by three women faculty who said the male-dominated humanities made women faculty “feeling like the housemaids in Upstairs Downstairs.”

However, support came from administrators such as Ernestine Friedl and Richard White, and with Fish as chair, who had promised Tompkins, “I will change it.”

Things did change. As more new female hires joined departments across the humanities, Tompkins found allies. “As I learned, body count really matters,” Tompkins said. “More than ideology.”

Drawing on ideas from colleagues, Tompkins also found the freedom, she recalled, to “break out outside the literary canon and traditional norms of classroom teaching.”

Tompkins described a course trip she led to the North Carolina coast, where students read and discussed Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick in personal ways. “I was evolving in my notions of what is the proper response to a literary text. I didn’t feel the idea that an intellectual response was the only proper one was sufficient anymore. I wanted to experiment with different ways of experiencing the text.”

Fish and Tompkins left Duke in 1999 for the University of Illinois at Chicago: Fish became dean of the college of liberal arts and sciences, and Tompkins joined the college of education. Fish, 86, is currently the Floersheimer Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law at Yeshiva University's Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law.

What Tompkins said she now realizes is that Duke University was open to change. “From the outside, it doesn’t look that way, with all its Gothic buildings. The style is conservative, but Duke turned out to be a place to explore different ways of teaching and learning.

“Duke gave me a chance to grow both as a professor and as a human being,” Tompkins added. “I was a different person when I left Duke 13 years later. I wasn’t as grateful as I should have been at the time, but I am now.”