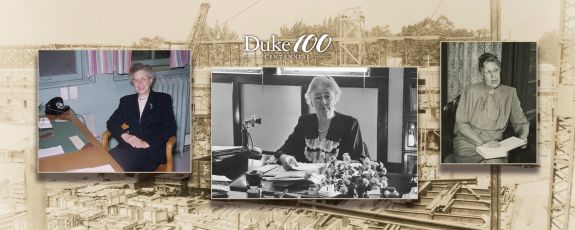

The Women Behind the Making of Duke’s Woman’s College

The establishment of Duke in 1924 paved the way for the Woman’s College to open in 1930 on East Campus

The Women Behind the Making of Duke’s Woman’s College

The establishment of Duke in 1924 paved the way for the Woman’s College to open in 1930 on East Campus

The Women Behind the Making of Duke’s Woman’s College

The establishment of Duke in 1924 paved the way for the Woman’s College to open in 1930 on East Campus

This story is part of Working@Duke's celebration of Duke's Centennial year. Working@Duke is highlighting historical workforce issues and showcasing employees in a special series through 2024.

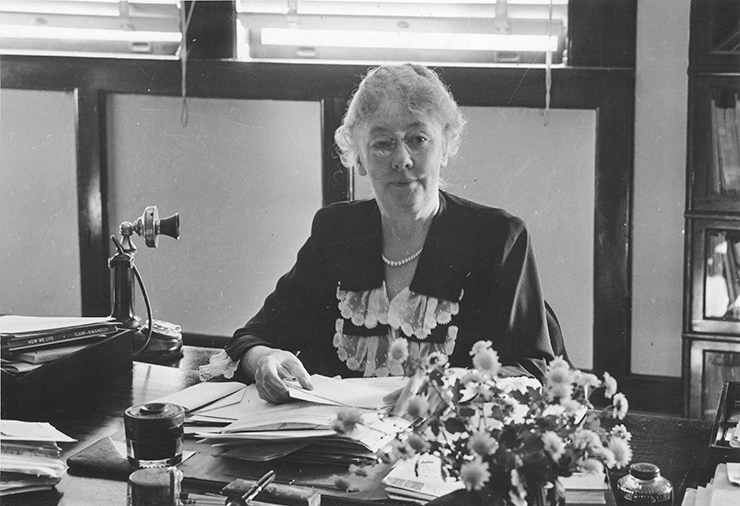

When a friend from Durham asked Alice Baldwin in early 1923 if she would be interested in a position overseeing women’s studies at Trinity College, she had a quick answer.

“Not in the least,” she recounted in her memoir, “The Woman’s College as I Remember It.”

Not long afterward, a Trinity College professor and director of the school’s summer session asked the same question to Baldwin, a former Dean of Women at Fargo College, and she replied, “Not at all.”

But the Trinity College professor was persistent, and the third time he asked, Baldwin accepted a temporary appointment as acting Dean of Women in the 1923 summer session at Trinity College before the Woman’s College opened. She was 44 years old and had never been to the South.

“I enjoyed those six weeks, hot as it was,” the Maine native wrote in 1959.

The appointment turned into a full-time position that eventually blossomed into the most pivotal role in the pioneering establishment of Duke’s Woman’s College, which opened with about 450 women in September 1930 and existed as a coordinate college to Trinity College until 1972 on what’s now East Campus.

Reluctant as Baldwin was to initially take the position, she would become the greatest champion for the women who moved into East Campus when men relocated to Duke’s newly opened West Campus in 1930. She set in motion a series of pivotal decisions – including the establishment of a physical education department and an arts department led by other trailblazing women – just after Duke was established in 1924.

“I was a product of coeducation, but if a coordinate college was to be developed, our job was to make it the best possible of its kind,” Baldwin wrote in her memoir.

As Duke celebrates its Centennial in 2024, women such as Baldwin, Physical Education Instructor Julia Grout and the creator of the arts department, Katherine Gilbert, show that the Woman’s College that opened in September 1930 was a pioneering chapter in the history of Duke University.

Alice Baldwin, the reluctant dean

Baldwin never planned to lead a college; she wanted to be a history professor. But as she wrapped up her doctoral degree at University of Chicago, her supervising professor advised that there was not much future for her there.

So when Trinity College President William Preston Few began asking whether she’d be interested in staying on full time, she considered it – though she was stunned when Few “asked if I could take criticism and disappointment without weeping!”

Anyone who knew Baldwin well would have known that was not a question to ask.

“She was a force to be reckoned with,” said Mary Duke Trent Jones, great-granddaughter of Benjamin N. Duke. Jones’ mother, Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans, was close friends with Baldwin, so Jones saw her feistiness first-hand. “You didn’t fool around with her. She was a kind but forceful dean.”

Baldwin was such a towering figure in Duke's history, that one of the most prominent buildings on East Campus, the auditorium anchoring the campus, is named in her honor.

Baldwin fought for equal rights for her female students from the very first time she ate at the dining hall at Trinity College and noted that she and female students were not provided a napkin. So she bought linens for students, with funds coming from her $3,000 salary, with $800 of that designated for Baldwin’s room and board – a sum that infuriated her when she learned that subsequent Woman’s College educators hired were paying $600 per year.

Among Baldwin’s early requests as the dean for the Woman’s College related to the physical setup as East Campus was transformed to the Woman’s College domain: bathrooms should include showers; parlors in dormitories should have fireplaces; the special design of study chairs for women should be proportioned to fit their backs; and a large iron fence surrounding the women’s dorm quadrangle was not necessary.

More important, though, was lobbying against Few’s belief that women should have “separate but equal” academic opportunities. Before the official opening of the Woman’s College, Baldwin taught a junior-senior class in history in 1926 – the first time a woman taught an advanced class at Duke.

And Baldwin pointed out that duplicate classes on the two campuses was financially impractical. By 1934, there were 70 courses on East Campus in which only women were enrolled and 220 courses with mixed enrollment on both campuses.

“My chief aims were to have full opportunities for the women to share in all academic life; to have the advantages of the university libraries, laboratories, faculty, while at the same time giving them the opportunity to develop leadership and college spirit through their own organizations,” Baldwin wrote.

Despite all her work to get the Woman’s College established, Baldwin was not on campus when it opened Sept. 24, 1930. She was ill and taken to Duke Hospital badly dehydrated, where she remained for two weeks as 300 new women (and 137 upper-year students) started at the college.

But by then, Baldwin already had hired a supporting cast to help her launch the Woman’s College.

“I was especially fortunate in having such women as these and those on the faculty whose ability and devotion played such an important part in building the kind of College we envisioned,” Baldwin wrote.

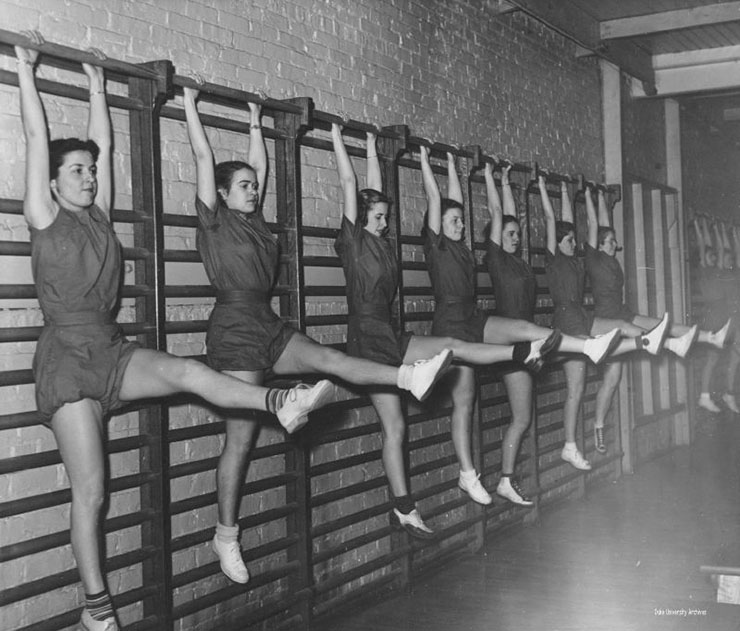

Julia Grout, the fiery P.E. teacher

One stipulation for accreditation of the Woman’s College by the American Association of University Women was a physical education program.

That’s why Julia Grout was among the first instructors Baldwin hired, in September 1924. The graduate of Holyoke and Wellesley “developed a department which … won recognition from the AAUW as well as from our own faculty,” one Duke colleague wrote to Grout upon her retirement in 1964.

Grout, who was called “Jerry” by her closest friends, spent 40 years at the helm of the physical education department, advocating for better facilities for women for the duration of her tenure.

In Grout’s memoir, “As You Were: Or Forty Years of ‘Happenings’ in the Department of Health and Physical Education,” she wrote that the first East Campus gym floor developed an “undulating surface,” the water in the swimming pool was an “opaque brown” and the roof above the pool had rotted and sagged after a snowstorm.

Early classes included horseback riding, swimming, gymnastics, tennis and archery, though Grout admitted that she had taken just three horseback riding classes, herself, before offering it as a course at the Woman’s College.

Additionally, all first-year students were required to take a class in “body mechanics,” in which the women were taught to “walk properly, to stand, sit and move gracefully and to handle the body efficiently in everyday activities such as carrying and lifting heavy objects, balancing, going up and down stairs, etc.”

But the department grew, and the focus shifted over the years, and in 1942, she received approval to offer Health and Physical Education as a major for students preparing to teach in secondary school.

In a 1946 speech, Grout said she “arrived in the era of high heels and debutant slouch,” but by the time she retired in 1964, “physical education today is considered to be more than exercise for amusement or discipline or to cure distortions.”

“There was never a time during the 40 years that I wished I were in another profession or in another place,” Grout wrote. “Starting from scratch – the first full-time teacher of physical education for women, I had the satisfaction of seeing our department develop through the years, along with and as a part of, the development of Trinity College into a great university.”

Katherine Gilbert, bringing arts to Duke

An early deficiency Baldwin identified at Duke and the Woman’s College was a lack of attention to cultural activities such as music and art.

“It is hard now to realize how little good music there was in the University and in Durham in those days,” Baldwin wrote.

That’s part of the reason why Baldwin sought to create a Department of Aesthetics, Art and Music at the Woman’s College, modeled after a similar program at Cornell University.

She tapped Katherine Gilbert to form the department. Gilbert had been appointed a professor of philosophy at Duke in 1930, the first woman to become a full professor. The innovative department was established in 1941.

Gilbert, who was so influential that Gilbert-Addoms Residence Hall was named after her in 1957, was often overshadowed at Duke by her husband, English professor Alan Gilbert, but she was revered by her students who valued her insight and intellect.

Gilbert died of cancer in 1952 at age 65.

“Such a teacher is Dr. Katherine Gilbert she turns students into disciples,” an editorial in the Duke Chronicle said after her death. “She offers more than facts, opinions and analyses – which may be found in any first-class text. She offers a personality, a living and inspiring embodiment of a fruitful and rich existence. The true work of art is man, as he recreates himself, and the way and the possibilities of such creation are taught by teachers like Mrs. Gilbert, who is the personification of the beauty she teaches. We are brought to say like Plato or Socrates, that this is the wisest and justest and best person we know and our lives are forever different for the knowing.”

Such an influential and impactful instructor is precisely what Baldwin sought to bring to the Woman’s College to shape the women who attended the school.

“I believed and still believe that there should be on the faculty a fair number of women whose scholarship and teaching ability should win and hold the respect of both students and faculty and who are interested in working with the women students in various ways, who are given positions of high rank, by no means always as instructors, and who will serve as examples of what women can achieve in the academic world,” Baldwin wrote in her memoir.

And for 42 years, the Woman’s College did just that – showed women what they could achieve in academics when surrounded by influential leaders such as Baldwin, Grout and Gilbert.

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs to Working@Duke.

Follow Working@Duke on X (Twitter),FacebookandInstagramand subscribe on YouTube.