A Walk with Wall: The Enduring Legacy of George W. Wall and George-Frank Wall

As the South struggled against progress, refusing to integrate its freed population, opportunities for newly emancipated people like George were scarce. George, at just 11 years old, transitioned from slavery to indentured servitude to Thomas White, a prominent member of the Randolph community and grandfather of a physics professor at nearby Trinity College. Ever astute and observant, George understood the value of this connection and the window that had opened to new possibilities.

George would eventually approach Braxton Craven, the president of Trinity College, and secure a role that would eventually span more than half a century. As a property steward at what would later become Duke University, George managed general maintenance and honed various technical skills while working on campus. His role was crucial in keeping the college operational and well-maintained, and he excelled at this work. So much so that in 1892, at the request of the then Trinity College President John F. Crowell, George was asked if he, and his family, would relocate to Durham as Trinity College itself moved to the newly burgeoning tobacco capital.

“The legacy of George W. Wall and his son George-Frank Wall is a testament to Black resilience and empowerment against the backdrop of systemic racism and segregation. Their pivotal roles at Duke University and the founding of Walltown not only highlight individual success but also underscore collective progress in Durham.”

George recognized that this move was not just geographical but represented a significant leap into a new community pulsating with the promise of growth and prosperity. As the only non-faculty employee to move, he uprooted his family and grasped the opportunity presented. Initially living on the college grounds, George became a cornerstone of the campus community, and his life became intertwined with the area's development. Like other Black workers of the time, George leveraged his relationships and saved hard-earned “Sunday money” (extra wage labor done on the weekends) for a piece of land for him and his family to call their own.

Just beyond the college grounds, a stretch of woods had been turned into residential blocks and posted for sale; the land was vulnerable to flooding and not prime for building, yet George once again saw an open door. Despite the average salary for Black laborers, which was less than $400 a year, he invested $50 and purchased a plot of land on July 21, 1899. Using his years of experience and skills, he built a one-story wood-frame cottage, complete with a chimney and stoop in front to sit on during warm evenings.

Soon, other Black families began settling nearby, drawn by the promise of community and security in a still-segregated Durham. This growing enclave of working-class Black families formed a tight-knit community that would eventually be known as Walltown. The development of Walltown was emblematic of Durham's broader expansion during this time and what W.E.B. Du Bois described as the seat of a new "group economy." This economy was a self-sustaining circle of social interaction, education, commerce, and even manufacturing, predominantly run by and for Black people.

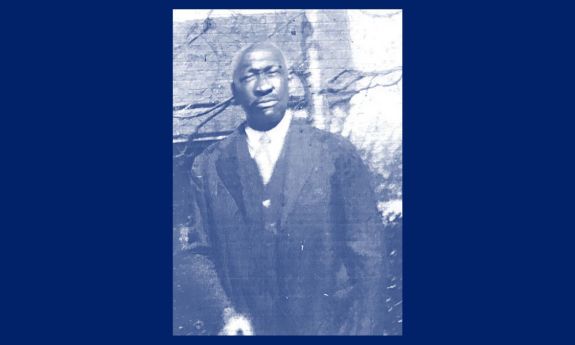

George was entirely committed to his work, continuing to ensure that the expanding campus of Duke University was well-kept even after “retirement” when he began receiving a pension for his years of service. Well known to generations of students who greeted him as he traversed the campus, after 50 years of continuous service to Trinity and Duke, George passed on in the winter of 1930. George W. Wall's nine children, and notably George-Frank Wall, proudly carried forward the family's tradition at Duke University and Walltown.

George-Frank Wall, who was born in 1887, often helped his father in his caretaking duties at Trinity and eventually Duke, and like his father, he too became an integral part of Durham and campus life, raising four sons in Walltown and continuing to work at Duke until his death in 1953. With deep relationships in the Duke community, he elected Duke President Robert Flowers as executor of his estate.

Duke did not admit Black Students at the time of his death, still George-Frank bequeathed $100 in recognition of his time employed and as a seed planted for a legacy of Wall descendants that he knew would come after him. This gift was added to the scholarship fund, and the first Black undergraduates enrolled 10 years after his death. In the years since there are no confirmed descendants of the elder George Wall’s nine children who have graduated from Duke.

The legacy of George W. Wall and his son George-Frank Wall is a testament to Black resilience and empowerment against the backdrop of systemic racism and segregation. Their pivotal roles at Duke University and the founding of Walltown not only highlight individual success but also underscore collective progress in Durham. Despite enduring significant barriers, they established a legacy of community strength and independence that continues to inspire and influence.