Marine Lab Connects with Coastal Neighbors

“We call this paradise ‘home,’ Nelson Johnson said as he gazed out over the water surrounding the Duke University Marine Lab campus in Beaufort, North Carolina.

Johnson lives in nearby Emerald Isle. Like nearly 600 others on a recent Saturday, he and three neighbors dropped by the lab’s June open house, paying a visit to the area’s most unusual next-door neighbor. The year-round marine lab campus, on Pivers Island, is part of Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment.

The Duke University Marine Lab sits in Beaufort on the beautiful North Carolina coast.

At the lab’s first open house since COVID, researchers showed visitors how they monitor declining whale species, how ocean acidification impacts coastal waters, how to restore dwindling salt marshes that help the area thrive, and more at 25 demonstration stations. They shared the many ways in which this local paradise is not immune to the impacts of climate change and global warming caused by fossil fuel emissions that create greenhouse gases.

“I think some people are hesitant to talk about climate change as some large global phenomenon, but people who have lived here for a long time can see changes in their community,” said Dana Hunt, associate professor of microbial ecology at the Marine Lab. “That’s often a place to reach people who might be more hesitant to talk about global warming, but they can say, ‘sea level rise, I’m seeing increased flooding in my community. That’s something that affects me.’ I think we can reach people by coming to them where they are.”

Created in 1938 on Beaufort Inlet, the lab — Duke’s “true East campus” as Duke Marine Lab Director Andy Read puts it — provides the perfect setting for research with direct impacts for coastal North Carolina communities. Nearly 90 years later, that mission includes understanding how the coast is experiencing climate change.

“We are very active in marine science, marine conservation and understanding coastal communities that depend on the ocean,” explained Read, the Stephen A. Toth Professor of Marine Biology who chairs the Marine Science Conservation Division at the Nicholas School of the Environment.

Robin Faggart and Shady Terrell, who made the short drive from Emerald Isle with Johnson, learned about the key role their marine lab neighbor plays in exploring communities within the community, from the largest marine mammals to the smallest organisms on the North Carolina coast.

“I knew the lab existed but had no idea what this was, and this is awesome,” said Faggart. Terrell added, “I love to fish, and I love to be in the water, on the water. Everything they are doing here will in some way impact one of those things.”

The Largest Locals:

Studying and Conserving Marine Mammals

Andy Read speaks to visitors in bare feet, the same state he works in on the water.

“We tracked a whale who stayed submerged three hours and 22 minutes,” Andy Read told a packed room of open house visitors in the Repass Ocean Conservation Center of the Duke Marine Lab. Read usually instructs students in this room with floor-to-ceiling windows that look out on Beaufort Inlet and passing dolphins.

“Wooo,” audible surprise and admiration came from the crowd listening to Read’s anecdotes about the habits and diving capabilities of whales and dolphins.

“They are mammals like we are,” said Read. “How do they do that?” He looks every bit as awed by the marine mammals he is describing as his audience.

“My lab is interested in trying to find solutions to conservation problems,” said Read. “We work with species locally like Atlantic right whales and species nationally like the little vaquitas. That’s the little porpoise with only 10 animals left in the in the whole species in Mexico.”

The peril of the vaquitas draws an audible reaction from the audience, who later learn that as few as 360 right whales remain in the world with only 70 reproducing females.

“We have a big project here in North Carolina looking at the effects of sonar, military sonars, on deep diving whales,” Read said.

The U.S. Navy designs sonar powerful enough to locate distant or hiding submarines. The high intensity sonar interferes with the diving patterns of beaked whales who feed at deep levels.

Whales are drawn to the coast of North Carolina by the blending of the Gulf Stream and Labrador Current, which creates a rich food source. That makes Beaufort a very good place to study the whales, their habits, and the effects of Navy sonar.

“We have surveys that fly every day, from North Carolina to Florida, looking for the whales,” said Read. The aerial surveys keep tabs on the whales’ movements, identifying moms and new babies. Last year, the whale survey identified an animal in distress that a Marine Lab vessel rushed to helped save.

“Because they’re iconic animals, because people care about them, I think the work we do is really important,” said Read. “Especially in a country like ours that is well-resourced, we should be able to find ways where we can coexist with populations of animals like whales including here in Beaufort.”

A young girl in the audience raised her hand. “Why do the male dolphins fight each other?”

“Girls!” Read answered to laughter in the room. He carefully explained that male dolphins work in alliance to protect females in their community.

Visitors also asked about offshore wind turbines, the increase of manatees in North Carolina’s warming waters, and laws to reduce boat speeds in local channels. Read attended to each question, always pointing to science and years of research conducted in local coastal waters.

“My lab is interested in trying to find solutions to conservation problems. We work with species locally like Atlantic right whales and species nationally like the little Vaquitas.”

Andy Read,

Director, Duke Marine Lab

Where the Seagrass Grows:

Duke Restore

A young visitor learns about restoring seagrass during Duke University Marine Lab open house.

“I want to see the oysters,” nine-year-old Cherish Hester told her grandfather, Shawn Singletary.

They stood on the porch at the lab’s Pilkey Building looking at baby oysters through a microscope. Singletary grew up in Beaufort’s African American community with its distinctive fishing and oystering culture. He remembers family members harvesting their own oysters.

“A lot of them did it right here on the Beaufort-Morehead Causeway,” said Singletary. “When I was growing up, going to Beaufort Elementary School, we would take a butter knife to school with us that day, jump across the trestle at Beaufort Elementary, go down the trestle, jump right off the trestle, sit down on the oyster bed, and just (slurping noise). That was years ago. The trestle’s still there, but the area we used to harvest from dried up. They put buildings and everything around it.”

Singletary and his granddaughter made their way over to ecologist Brian Silliman’s seagrass lab demonstration, gravitating to the oyster shells strewn out on the table. The Rachel Carson Distinguished Professor of Marine Conservation Biology, Silliman researches the loss of local oyster grounds and die-off of the saltmarshes the oysters inhabit.

“I study how species interact and affect coastal ecosystems, how climate change affects coastal ecosystems, and how these habitats and our near-shore environments help humans,” said Silliman.

He said warming water kills large swaths of oyster reefs and salt marshes. Rising sea levels compress salt marshes. And seawalls and development prevent marshes from migrating naturally in response to rising seas.

Without salt marshes and oyster reefs, North Carolina’s coastal communities become more vulnerable to climate and increasing storms. And in this way, climate change is also creating economic stress.

Silliman’s Duke Restore project finds creative ways to restore ecosystems, rather than focusing on the degradation of those ecosystems, coastal pollution and coastal development.

“Brian and his students are like, ‘Let's make those things better,’” said Read. “Let's build back better ecosystems. Let's use scientific principles to make seagrass ecosystems, to make coral ecosystems better, to build shorelines and living shorelines like the one here, not seawalls.”

“We're coming up with innovative ways to regrow salt marshes in areas where they were destroyed, due to various human activities,” said Silliman.

“For example, one of the best ways to get marshes to grow back is to put an oyster reef in front of an injured salt marsh that's being exposed to waves. Once you do that, they have a water baffle in front of them. They can start to regrow. They're not continually eroded, and they can grow seaward,” Silliman said. “And we provide data analysis and design suggestions for enhancements with our collaborators, like the Coastal Federation.”

The Restore Lab changed the paradigm by harnessing what already exists in nature. Rather than replanting sea grass spaced out as you would in farming, they plant in clumps allowing plants to interact.

“And when they interact, it’s in a positive way,” said Silliman. “They help each other deal with waves. They share oxygen through their roots. We can increase growth rates by 400%.

Another innovation is putting clams on the roots of seagrasses.

“We’re coming up with innovative ways to regrow salt marshes in areas where they were destroyed, due to various human activities.”

Brian Silliman

Director, Duke Wetland and Coasts Center

“It's like a fertilizer state,” explained Silliman. “You get a 300% increase in growth rates. We're working to establish a seagrass farm here at Duke to provide the state of North Carolina with a continual and a low-cost seagrass seed supply. We're trying to work now with the drone center at Duke, and we're going to deliver seagrass seeds that are glued to clams out into the environment and get rid of our need for boats or divers and thereby increase success of plantings and decrease costs.”

Ultimately, salt marshes and other coastal ecosystems help humans, providing economic boosts through the production of seafood such as blue crabs and shrimp. They also protect our coastal communities from storms in two ways.

“They dampen the waves as they come into the shoreline, so they're less strong and get less erosion, and they act like giant sponges,” said Silliman. “They also clean our water. They absorb the nutrients and toxins that come run off the land and prevent it from getting into the water in high concentrations. The other thing is they clean our air. They absorb tons and tons of carbon from the atmosphere. They put it in these in their root system, like you see right here. And the beautiful thing about salt marshes is that root system is like a safe deposit box because it's flooded by water.”

From its test bed in North Carolina, Duke Restore’s research is being used throughout the world to change salt marsh growth rates. For Singletary, he feels the impacts at home. “Just being from this area and being out on the water, you just never know behind the scenes, and I’m just grateful for this. It means a lot because it keeps everybody else in track of what needs to be done in order for us to go on doing our own traditions.”

Small but Mighty:

Microbes and Ocean Acidification

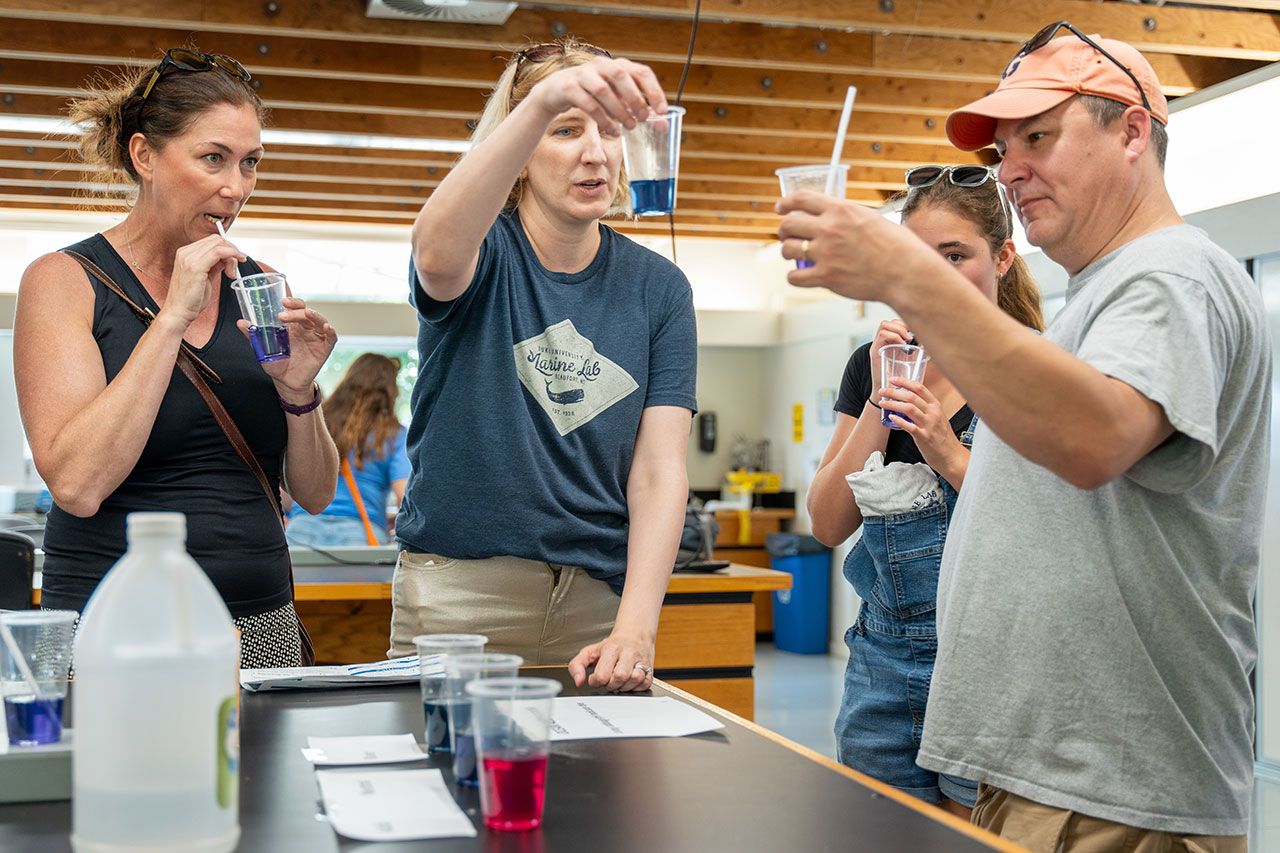

Open house visitor Daniel Wall and his 6-year-old son Gavin Wall take part in Dana Hunt’s ocean acidification experiment.

Microbes. They don’t offer the expansive views of salt marshes nor compare to whales when it comes to size, but they are necessary to all life forms. That’s big.

“They are small but mighty,” Dana Hunt said. “My research focuses on microbes, the smallest most abundant organisms on the planet. They perform cycling of carbon and biogeochemistry. They provide us with the oxygen we breathe, and without them our world wouldn’t exist.”

Microbes – microscopically small bacteria, fungi, viruses and animals – are the base of the food web. That makes Hunt’s work foundational to understanding how the ocean works and how the ocean responds to human-driven climate change. Studying local water samples weekly for the last 15 years, her long-term ecological research project is the first of its kind in this area. Hunt and students in her lab collect samples right from the marine lab dock.

“We examine how microbes respond to annual cycles and environmental variables, as well as long term trends in climate such as ocean warming or ocean acidification, Hunt said. “What that allows us to do is look at extreme events. We have things like hurricanes or storms, and we can capture that event, but we can also compare it to kind of the normal baseline changes in the microbiome.”

Ocean acidification is when the ocean becomes more acidic by absorbing the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere when humans burn fossil fuels. To demonstrate ocean acidification and its corrosive damage, Hunt and Duke rising sophomore Akshaya Mohan offered open house visitors a cup of cabbage juice.

“If one or all of you would like to blow into this cabbage juice,” Hunt instructed their visitors.

Eight-year-old Bradley Wall and his six-year-old brother plunged their straws into the juice, game for the experiment.

“We were adding carbon dioxide to the cabbage juice,” Bradley explained.

“We have little cups of cabbage juice, which is a PH indicator,” said Mahon. “It should change colors as it gets more acidic or more basic. If you blow into the cabbage juice with a straw, putting the carbon dioxide with your breath into it, it should change colors from blue to a more purple which shows how it’s more acidic. There are lots of organisms that rely on being able to precipitate calcium carbonate. Oysters — you see oysters around here everywhere — especially juvenile oysters, have a hard time precipitating calcium carbonate when the ocean is more acidic.”

A native of nearby Morehead City, Jessi Wall watched her sons’ cups of cabbage juice transform from blue to a bright pinkish purple. She left with a different view of the Marine Lab as a long-time neighbor.

“When we drive by and just see the sign for the Marine Lab, you don’t know what’s back here,” said Jessi Wall. “You don’t have a sense of ownership, a sense of engagement. Being able to walk in and see everything that’s going on makes you feel a bit of ownership in having this locally.”

In a community with a rich fishing tradition, Hunt studies the microbes that support local fisheries and she sees that local changes and climate vulnerabilities go beyond the shoreline.

“I’ve had people talk to me about seeing farmland become something they can no longer use for agriculture because of salinity,” said Hunt. “Because either due to storms or sea level rise, salinity is encroaching on things that used to be used as agricultural lands. Sunny day flooding is a thing that is accessible to them in that they can see that change in their own lifetime. Even for myself since I moved here, I’ve become so much more aware of sea level rise and storms because you see them and how they affect you and your community.”

Jessi Wall,

“Being able to walk in and see everything that’s going on makes you feel a bit of ownership in having this locally.”

Morehead City native

”How organisms in the ocean and the terrestrial environment respond to climate change, I think will affect all of us, as well as how ecosystems respond to things like storms,” Hunt said. “Let's use scientific principles to make seagrass ecosystems, to make coral ecosystems better, to build shorelines and living shorelines like the one here, not seawalls.”

The Duke University Marine Lab has been a member of the local community since its founding.

A Constant Presence

While the students from Duke and other institutions study at the lab for just weeks or full semesters, many researchers, like Hunt, live in the local community. They have a presence here.

“I think that’s important because we’re out in the community,” said Hunt. “We’re not in a big campus. We all live in the community, and we work in the community, and we have families. It allows us to uniquely access people who might not interact with people from institutes of higher education frequently.”

For coastal North Carolina residents like Daniel Wall, that presence makes a difference far beyond the activities his sons enjoyed at the open house.

“I think it’s great to know they are in our community and working towards gathering the data to influence changes or policy,” said Wall. “It’s great for the community, and it’s a great area to do it because it’s very coastal, or all coastal, and this area thrives on that.”