Digital Humanities on the Rise

Digital humanities scholar Victoria Szabo talks about some of the latest digital arts and history projects at Duke that are allowing students to learn in new ways

If you were a student here at Duke now taking digital humanities classes, how could you learn differently from five or 10 years ago?

We have more things available online. So, when I teach a class, people don't usually buy books anymore or even print stuff out. They're just reading it online. They get kind of mad if you expect them to look at a book.

And in the classroom, you can all look at those resources. One of the things that that we do a lot is try and think about how you can learn by making. If you’re studying a text or a historical period or an image, maybe you're not only reading about it or writing about it, but you’re also making a creative project. That or a digital project that helps you to understand it. So, if you’re creating an annotated edition of a text, maybe you’re adding in web elements. Or, if you’re doing an analysis of an image, you can create hotspot areas and explain them. And then in the process of doing that, you, the instructor, can learn because you’re someone who’s helping to create educational materials at the same time. So, this kind of active learning also applies even for things like the history of architecture.

“The making process in digital humanities becomes important to the learning process. Even if the thing you make isn’t all that awesome, like maybe you’re not going to put it in a museum, it’s still the process of doing.”

Victoria Szabo

So, the making process in digital humanities becomes important to the learning process. Even if the thing you make isn’t all that awesome, like maybe you’re not going to put it in a museum, it’s still the process of doing. And that’s why so many of our courses tend to have that mixture of making something as well as studying it. That’s a big difference that’s become more and more accepted.

Can a student major in the digital humanities?

In a way, yes. We recently created an interdepartmental major and minor called Computational Media, which sits between Computer Science and Visual and Media Studies. This curricular path builds upon ongoing relationships across the two programs and offers a way forward for students who want to specialize in doing digital humanities and computational media in greater depth from both the computational and humanistic perspectives. In addition, we have an MA in Digital Humanities/Computational Media and an interdisciplinary PhD in Computational Media, Arts & Cultures that are related. So, we have opportunities at all levels – from first year students to PhDs.

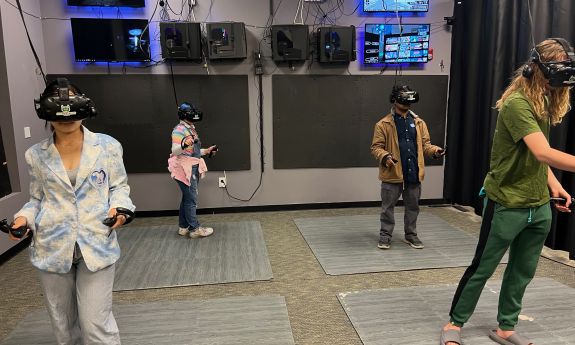

Some opportunities are related to games. We have a FOCUS cluster; it’s called Virtual Realities, Fictional Worlds and Games. The first-year students were super excited about that because it allowed them to take seriously something that they thought of as their hobby or their activity and turned it into an object of critique. So that was popular. Then, classes that are related to people learning how to do virtual worlds, creation or game engine design.

Can you share an example of how digital media has shaped our history?

I think about what the equivalent is of the Gutenberg Bible. The rise of printing that was the distribution of knowledge. I don't know if there’s like any one thing.

I think having a much richer understanding of the cultural history and the landscape that we get out of digital access is one of the most transformative things, and it’s really simple because it’s not even talking about making all this digital stuff. It’s just talking about access. And that’s why I ended up going in digital humanities myself, trying to figure out how to tell a fuller story.

What is your new project focusing on Durham all about?

The project that we’re doing is about Durham in 1924 and trying to give a portrait of the city a hundred years ago. We’re calling this exhibition that we’re creating for the Rubenstein Library “A Worthy City.”

The reason we’re calling it that is because when the Duke [family] gave all this money to turn Trinity College into Duke University, they had all these aspirations for what the university would look like. But the city itself needed to be transformed. It had been, and it still is a manufacturing place. It was a tobacco distribution center. It was a railroad stop. It was all of that. But then it was also trying to become this place that’s worthy of an elite university.

And so, what does that mean? That means things that we would now see as gentrification happening. Transformation of the landscape, the built environment. And the change of the university changes the dynamics of what the neighborhoods look like.

And if you listen to the Duke leaders, of course, they’re going to talk about this wonderful celebratory arc of this small regional school to this international powerhouse. And that’s true. But there were also people who are already here whose lives were impacted and changed by the insertion of Duke and another higher education institutions into the area.

A Digital Portrait of Durham From Long Ago

“A Worthy Place: Duke, Durham, and the World in the 1920s and 30s” will open in the Chappell Gallery in Rubenstein Library in January 2025. It will emphasize archival materials from the Perkins Library Collections and how these materials help tell the story of the city at the time of Duke’s inception as a university. There will be interactive digital maps and other media in the exhibit space, and we will also have a related, corresponding online exhibition on the web, which will be accessible via QR codes from the exhibit and from a URL we’ll share publicly and via postcards.

Aneesa Shaw is a current N.C. Central University student who worked this summer as a Charmaine McKissick-Melton Fellow in University Communications and Marketing.