Faculty Find a Home for Bright Minds

Since its beginning, Duke proves to be a place where faculty can thrive

Upon returning to the United States in January 1927, Pearse traveled directly to Duke, where a Zoology faculty position awaited and his wife and two children had settled in a home on Club Boulevard.

In correspondence with friends, Pearse described Duke University – less than three years old at the time – as “unorganized” and, from a scientific perspective, “undeveloped.” But “the prospects for the future have promise,” he added.

Pearse became a major piece of that future. He founded the Duke University Marine Laboratory in 1938; conducted research in Asia, Africa and South America, and served on Duke’s zoology faculty until his retirement 1948.

To keep pace with academic aspirations, Duke’s faculty grew rapidly in the early years, jumping from 152 members in 1925 to 354 in 1930. To attract top teaching talent from across the country, Duke built 14 faculty houses on Campus Drive in the early 1930s.

Duke historian Robert Durden noted in his book, The Launching of Duke University 1924-49, that early faculty showed a high degree of loyalty to Duke because they “grew up” alongside the institution.

Now with 4,109 faculty, Duke remains a destination for bright minds, a place to build lasting connections.

Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement Abbas Benmamoun, who joined Duke in 2017, said he often hears how opportunities for interdisciplinary research and collaboration across disciplinary boundaries make scholars want to put down roots at Duke.

“There are so many opportunities to build deep connections and relationships here,” Benmamoun said. “And I really think it’s hard for faculty to walk away from community, especially when it’s a community that is enriching and where you feel that you have grown and thrived.”

Throughout the university’s first century, many influential thinkers found that fit at Duke.

In the 1930s, Duke welcomed leading German scholars, such as physicists Fritz London and Hertha Sponer, who fled fascism in Europe.

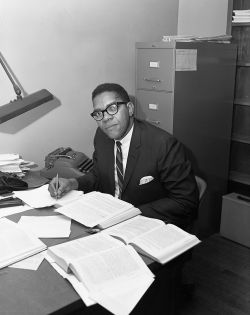

Students have learned from faculty such as jazz composer Mary Lou Williams and political scientist Samuel DuBois Cook, who joined Duke in 1966, becoming the first African American to hold a regular and/or tenured faculty appointment at a predominantly white southern college or university.

Two Nobel laureates, Drs. Robert Lefkowitz and Paul Modrich, continue to make Duke their academic home.

The Cultural Anthropology Department is home to six primary faculty with a quarter-century or more at Duke.

A bulletin board in their offices features photographs of current Professors Anne Allison, Lee Baker, Charles Piot, Ralph Litzinger and Orin Starn smiling into cameras in the 1990s.

They’ve all drawn inspiration from campus.

Piot said his books on the political economy and history of West Africa were enriched by ideas shared among colleagues.

Baker said a study abroad program that allowed students to conduct research in Ghana was the result of Duke’s support of ambitious ideas.

“At Duke, we found a great intellectual life, wonderful resources, a good place to live,” said Starn, who has taught at Duke since 1992. “All of those things have ended up keeping us here.”

Do you have a story you would like for us to cover for the Centennial year? Send ideas and photographs through our story idea form or write working@duke.edu.

Follow Working@Duke on X (Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram.