Taking a Larger View of the Universe

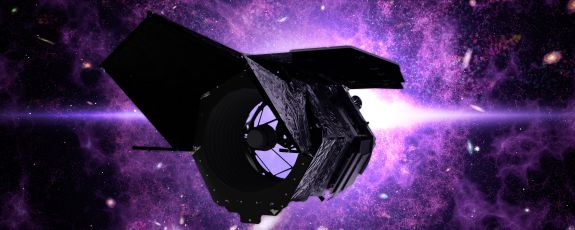

Once it’s launched into outer space in 2027, NASA’s next telescope will provide the “big picture” of the universe. But for two Duke scientists, preparations are already underway.

With the Roman Space telescope, “we're looking at observing twice as many objects per area of the sky than any other survey has."

Duke physics professor Michael Troxel

Described as Hubble’s “wide-eyed cousin,” the Roman will be able to image a swath of sky 100 times larger than Hubble could see at one time, but with the same level of detail.

Surveys that would have taken Hubble and other space telescopes a lifetime “will require just one month of operation for the Roman,” said Troxel, who is an associate professor of physics.

As the telescope orbits a million miles from Earth, its mirror will gather light from a billion galaxies and thousands of exploding stars in a quest to understand an enduring mystery about the growth of the universe:

If the universe were dominated by matter -- the stuff of stars and planets -- the pull of gravity should make the expansion of the universe slow down. Yet scientists in the 1990s were surprised to find that the expansion was not slowing down, it was actually speeding up.

The main goal of Roman is to pin down the cause of this cosmic acceleration, which scientists call “dark energy.”

Dark energy makes up roughly 70% of the universe, yet scientists have little idea what it is. With the Roman they hope to narrow down some of the possibilities.

Once the telescope is up and running, the Roman will send 1,375 gigabytes of data back to Earth each day, producing some 20,000 terabytes over its five-year mission.

Over 30 years from 1990 to 2020, the Hubble’s data archive amassed less than 1% of that.

Scolnic and Troxel are each co-leading multi-institutional teams that will help prepare for this data deluge by creating simulations, developing software and algorithms, and more, with funding support from NASA.

Troxel’s team is focused on a phenomenon called weak gravitational lensing, whereby telescope images of distant galaxies appear subtly distorted due to the bending of light by dark matter in between those galaxies and us.

Scolnic’s team will help scientists investigate how the universe expanded over time using the fading light from dying stars known as Type Ia supernovae.

“While we are co-leading different teams, one thing that really helps is our offices are just next door from each other, so we get to share a lot of new methods and information,” said Scolnic, who is also an associate professor of physics.

Now more than a decade in the making, the Roman mission has survived despite several attempts to cancel it, Scolnic added. In 2020 he and Troxel trudged through the corridors of Congress to defend the budget for the project, which remains on track for a 2027 launch date.

More than 90 proposals were submitted to NASA to gear up for the Roman mission, and the two proposals from Duke were among five teams selected for building the critical infrastructure needed up to and after launch. Overall, the grants will bring $12.5 million to Duke over the next five years, with opportunities for extensions.