Thanks for Your Service: America’s High But Hollow Support for the Military

In new book, Peter Feaver raises alarms about trends pulling the military into partisan politics

- Patriotism, particularly in times of war

- Performance – the perception the military is good at its mission

- Professional ethics – the sense that it behaves ethically

- Party – political differences in public confidence

- Personal connection to the military

- Public pressure – the sense of peer pressure to support the military

As in 2001, Feaver said the pillars of support for public confidence are trending downward.

“I find it ironic that after five years of studying the issue closely, I ended up more or less in the exact same place I was more than 20 years ago,” he said.

Below, Feaver discusses his book’s findings and how the public and policymakers can address its concerns.

DUKE TODAY: Across the board, the military for several decades has ranked high in surveys tracking public support. How do the current trends in public support compare to the historical pattern?

PETER FEAVER: This high confidence is a fairly well-known fact amongst the American people. They don't know many things about the military, but they do know that the military is held in high esteem. In itself, that’s an interesting fact. The reason why it is well known is, in part, because the military has become part of our civic religion. You can't watch a professional football game without a military flyover or a tribute to veterans and you can’t attend a basketball game without a military ROTC unit carrying the flag out. The military is part of our social and public rituals. They're salient in our collective mental space, even though Americans don’t know much more about the military beyond that.

Historically, this is a recent trend. The pattern from before the Cold War era was the Americans would love the civilian military, the proverbial “Minute Men” who would arise during the Civil War, World War II and then demobilize quickly after victory. We loved that military, but did not love the professional military. That seemed to change in the ’80s under Reagan for several reasons. One is when we got rid of the draft in 1973, we did not demobilize. Because we were in a Cold War, we needed a military and shifted to an all-volunteer force. But the all-volunteer force is really an all-recruited force. To recruit volunteers, you have to market to the population. Consumers of social media and entertainment media are getting bombarded with ads that encourage them or their young family members to serve. This all probably has some effect in raising support for the military, but not necessarily deepening our understanding of the military.

DUKE TODAY: But you say this high confidence is hollow? Can you explain why it appears to be cracking?

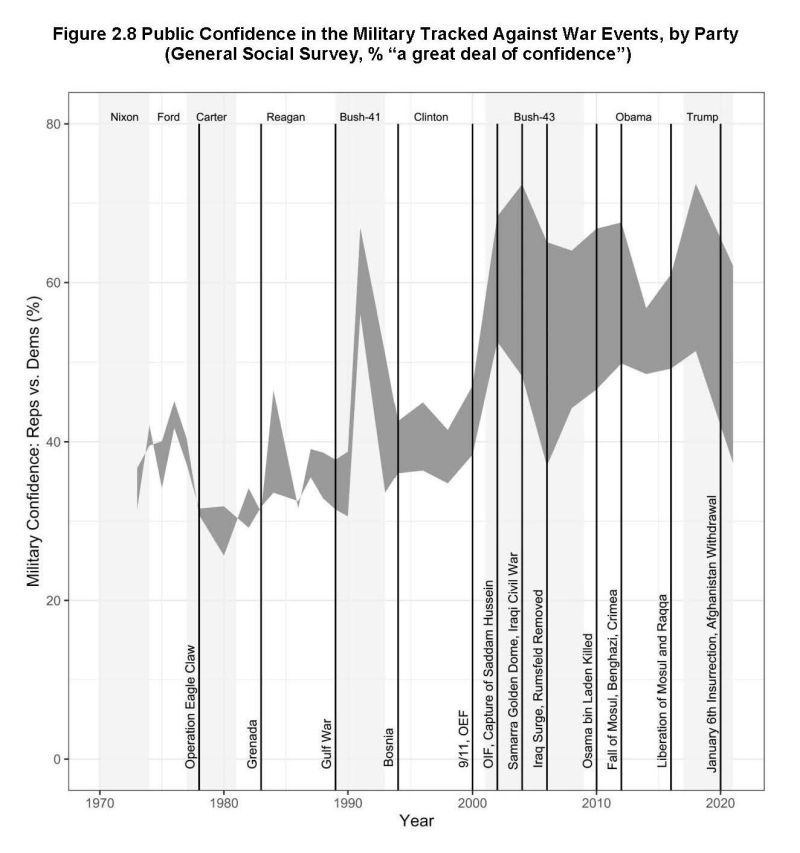

FEAVER: While public confidence is high in the aggregate, that masks differences within the American public. Most pronounced are party differences: Confidence has been super high for Republicans, and just medium high for Democrats.

The decline in the last three years is mostly among Republicans. I trace a lot of that to President Trump, Tucker Carlson and key Republican opinion leaders who are broadcasting an anti-military message with their attacks on senior military leaders. Their message may be that they love the military, they just hate these generals, but that still can drive down overall public confidence among Republicans.

Another key factor is peer pressure. This is the idea that you say you have confidence in the military because you think that's the correct answer to say, and here’s where in the book I get to cite “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

In a very funny way, this scene shows that certain segments of the population maybe don't really have high confidence in the military, but in the current moment they feel some pressure to say that they do. It turns out that when one uses survey techniques designed to tap into this kind of phenomenon it shows up significantly in public expressions of confidence in the military.

That is what I mean by “hollow support.” It also suggests that if it becomes politically correct to say you don't have confidence in the military, then you could see a rapid drop in the surveys.

DUKE TODAY: How is personal connection affecting support?

FEAVER: Our survey found if you serve, you're likely to have higher confidence in the military than somebody who didn’t serve. And even if you didn't, if your family member served, you’re likely to have high confidence compared to somebody from a family without any veterans. But of course, those numbers are dwindling as the World War II generation has died off and the draft generation is starting to get older.

So, we’re left with a population that shows high confidence in the military but in which fewer people have a personal connection to someone who has served. As those demographics continue, support for the military is going to go down, we just know that – unless there is some exogenous shock as happened on 9/11.

DUKE TODAY: At a moment where support for all national institutions is heading downward, why is it important to be concerned about this effect on the military?

FEAVER: It affects recruiting, at least on the margins. People with higher confidence in the military are more likely to join, and, perhaps more crucially, they're more likely to recommend to others that they join. The typical recruit has been persuaded to join in part by what he or she feels internally and in part by the collection of advertising and social forces – friends, parents, coaches, mentors -- saying you should do it. If confidence drops among those influencers they will be less likely to recommend military service and an already tough recruiting environment will become that much more difficult.

High confidence also is linked to the material support that defense experts say is necessary to meet threats from the Chinese and other sources.

The declining confidence in the military does not necessarily mean the military is no longer capable of meeting its mission, but it makes doing that mission more difficult.

So the military is right to want to keep confidence high. However, from the perspective of civil-military relations, even more troubling than declining confidence in the military is the total collapse of confidence in civilian institutions.

As I see it, the problem here is not the military is held in high esteem. The problem is that civilian institutions are held in low esteem. You’re not going to solve that problem by knocking the military down a peg or two. You solve it by trying to cultivate civic mindedness and civic pride and the rest of the democratic institutions on which we depend. That’s what I hope happens.

I hope we can create a norm that says we need to treat the military as non-combatants in the culture wars.

Peter D. Feaver

DUKE TODAY: You have recommendations in the book. What should the public and military be doing to build public support that is more sustainable?

FEAVER: One point is the public is sloppy in the way it thinks about good and bad behavior by the military. Partisanship has colored the way Americans approach this issue. The public seems to define a politicized military to mean the military aligning with the other party: When the military aligns with my party, that's not politicization!

This is very problematic for the military, which of course, has to serve the president no matter what party the president belongs to. This polarization is coloring and making it harder to enforce good norms in military behavior.

I hope this book will help push back on that. I hope we can create a norm that says we need to treat the military as non-combatants in the culture wars. Sen. Tuberville’s hold on military appointments (because of his opposition to the current abortion policy for servicewomen) is a dramatic example of making the military unwilling combatants in the culture wars, but not the only one.

This requires Republicans not to target the military, and it requires Democrats not to hide behind the military in defending controversial policies set by the Biden administration. These policies are for the administration to defend, not the military. And it requires that the military learn how to talk about their values without inadvertently sounding like culture warriors. Many of the cases that have triggered the most shrill critiques from the far-right wing of the Republican party can best be described as moments when senior military leaders tried to convey a reasonable point but ended up using language that has become so politicized that it is essentially “fighting words” in the culture war. The military have to avoid sounding that way.

I recommend that the military focus on two things: one is deservedness – being mission worthy, holding itself accountable, fixing mistakes, and not drinking their own bathwater about how wonderful they are, not reading their PR. Focus on being the best not boasting about being the best.

Secondly, the military should promote a view of national service that is broader than just military service that celebrates all the ways that we can contribute to the public good.

It also requires the military to not lean in on culturally divisive issues, as we have seen in some cases, particularly with some retired officers. The public tends not to make the fine distinctions between the current military and a retired officer that experts make and so when the retired military become partisan cheerleaders in presidential campaigns they are politicizing the active force whether or not they intend to do so.