Summer Camp Meets AI

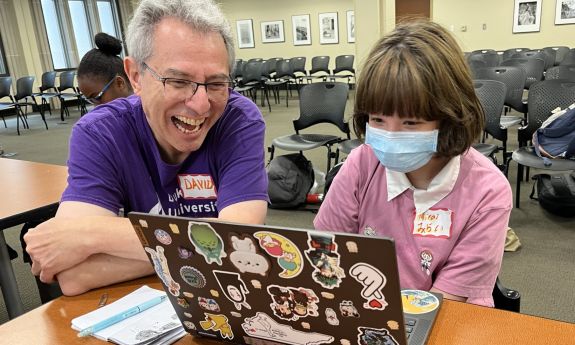

“This is a significant new innovation with an impact comparable to the introduction of the internet, the iPhone, genetic splicing,” said Duke PepsiCo Ed Tech Program Coordinator David Stein, who led the program.

Since ChatGPT rolled out, Stein has been working with Durham Public Schools and other community partners to experiment with generative AI and brainstorm ways to use the technology to address their needs.

Such tools are here to stay, so why not help students “learn how to use them responsibly?” Stein said.

"The time seemed right to take on AI."

David Stein

For many students in this summer’s program, these were their first chats with bots.

Take Dara Brodsky, a rising seventh grader at the Durham School of the Arts. She was one of several students in the program who tried using the technology to help write and illustrate books.

“The Tales of Levana,” as she calls it, is a fantasy novel featuring dragons, elves, wolves and shape-shifting creatures.

She came to the program with 40 pages already written.

“It's a little frustrating for me right now because I have a bad case of writer's block,” Brodsky said. “So I'm thinking about using ChatGPT to come up with ideas.”

Feeling stuck, she fed chunks of her writing to ChatGPT and asked it to help her continue the story.

Brodsky agonized over her first 40 self-written pages for three years, but in less than five seconds ChatGPT spat out suggestions for subsequent chapters, complete with dialogue and plot points.

When she didn’t like what ChatGPT wrote, she tweaked her prompt and asked it for another go. “Make this longer and more detailed,” she instructed the bot.

“It's definitely changing names,” said Brodsky as she pondered whether to take ChatGPT’s results and make them her own. “And it's not keeping the main character -- that’s strange.”

She also used a graphic design tool called Canva to come up with AI-generated images of scenes like “woods with a figure lurking in the background” or an “elven rider on a dragon’s back.”

“Sometimes the pictures of people are warped a little bit, and it's hard to get it to do exactly what you want,” Brodsky said. But after four tries she settled on an image for a chapter header.

What did she think of her collaborative experiment between human and machine?

“It's fun that I can use AI to help me come up with things,” Brodsky said. “But I don't want to use it for more than that; I want to keep my creative license.”

“I've read one too many books about the takeover of Earth by robots,” she quipped.

Over the course of the program, the students experimented with using ChatGPT, DALL-E, and other generative AI tools for much more than generating fiction. They also asked the bots to edit audio, come up with recipe suggestions, design their own business cards, even research colleges.

Given answers to questions like “what do you want to major in?” and “do you prefer lecture-style classes or discussion classes?” they asked, could ChatGPT suggest universities that would be good fits for them?

One afternoon, they held a mock debate about the technology’s pros and cons in the classroom, using ChatGPT to research viewpoints and anticipate counterarguments.

“It’s not trustworthy,” said one student from Lakewood Montessori Middle School, citing ChatGPT’s propensity to get things wrong or make things up.

“The training data could have biases that we don’t know about,” said another.

“It’s basically cheating,” someone added, referring to concerns that some students will try to pass off A.I.-generated text as their own.

Students representing the “pro” side fired back.

Some argued that schools have a responsibility to prepare students for a future where such tools are commonplace, even sought after.

“Are schools about preparing kids for 50 years ago, or are they about preparing kids for today?” said one student from the Durham School of the Arts.

Others thought bans were the wrong move because students could easily find a way around them.

“Children could go home and do whatever they want on their personal computers,” said a student from Jordan High School.

As the workshop wound down, one takeaway became clear: One way to address some fears -- particularly that generative AI tools could promote laziness or undermine critical thinking -- may be to have students actually try them out.

On the final day of the program, the students demoed some of the tools they had been exploring for their families to see.

“Let’s say I wanted ChatGPT to write a couplet about tomatoes,” said Soka Rosette, a rising ninth grader at Riverside High School.

With just a few clicks, she turned the labor of writing poetry into a task that could be breezed through in a matter of seconds.

“Amazing,” one parent gasped.

For fun, another parent said, “I want a limerick about why the Blue Jays are better than the Yankees.”

“Oh my gosh I love it,” said the Blue Jays fan, taking a screenshot of the results.

But when Rosette was asked how she might use AI tools when she headed off to high school in the fall, she shrugged. “I know it’s an option if I need it,” she said. “But I prefer to do things like writing and math myself. I just feel more satisfaction in doing it myself than telling something else to do it for me.”