Duke Heat Expert: ‘2023 May Be the Coolest Summer For the Rest of Our Lives’

Ashley Ward offers policy solutions to congressional staffers to mitigate extreme heat

Now it's time for elected leaders to play a more effective role, Ward said, to close what she called “a governance gap” by taking lessons from science and the insights from community engagement to create effective policies.

Ward recalled the now-legendary Chicago heat wave that caused 739 heat-related deaths in July 1995. The city with the big shoulders sagged under daytime temperatures rose as high as 110 degrees, with nighttime lows in the upper 70s and low 80s.

Ward said the majority of those who died lived in African American communities, and that men were twice as likely as women to die from the extreme temperatures.

Ward said the National Weather Service focuses a disproportionate amount of attention on what she describes as the nation’s urban heat islands.

“That’s really important. And we should definitely be continuing to work and think about that,” Ward says. “But people in rural areas of North Carolina, for example, have heat-related illness rates seven to 10 times the rates that we see in the urban counterparts of North Carolina."

The same study was replicated with similar results in Florida, and Ward said the same is likely true through much of the southeast.

Ward said the disparities are environmentally triggered, but result in “a socially organized disaster.”

Ward said the federal government will have to play a more active role to address extreme heat issues regionally. She also offered simple, common sense cooling solutions that promote positive health outcomes.

Governments should take social environments into consideration when categorizing and assessing who is at risk of health problems from extreme heat, Ward said.

Ward called for a regional approach to extreme heat risks backed by national resources, not unlike the role played by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Department of Housing and Urban Development or the Environmental Protection Agency. The heat scholar also said it's high time to expand the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 to include the impacts of heat and drought.

“The experience of heat vulnerability and exposure varies widely from one region to the next,” Ward said. “In the southern part of the United States, heat is a chronic event. However, in the Pacific Northwest, a lot of heat illness and injury that we see is fueled by what I call acute heat wave events.”

Ward pointed to other regional variables: the extreme daytime temperatures in the western part of the United States that lead to poor health outcomes are akin to high overnight temperatures in the eastern part of the country, for example.

Ward said recent incredibly high overnight temperatures, coupled with record-breaking daytime temperatures caused a significant number of health problems in the east, but also in other parts of the country.

“This is by far the most deadly of circumstances where you have the worst case scenario of both combined in one event,” Ward said. “That is why a regional approach is key.”

Cooling centers located in urban areas, for example, are not effective for residents in rural communities who may have to drive 30 minutes to reach the nearest cooling center, Ward said.

“Outreach and engagement in rural areas looks very different than it does in urban areas,” said Ward, who noted that during the Chicago heat wave the majority of deaths were among residents 65 or older, but here in North Carolina the number one risk group is males between the ages of 14 and 45.

Third, Ward called heat the “the least lonely disaster,” that’s commonly compounded by other events — such as a thunderstorm that knocks out power, cutting off access to air conditioning.

“Heat is also a contributing factor [for] other natural disasters like drought and wildfire,” Ward said. “And it aggravates the impact of other disasters, a hurricane or tornado, [which] by themselves are deadly and dangerous events. But they see their death toll explode in the days following when they’re accompanied by heat.”

The United States needs national cooling standards, Ward said.

“Air conditioning is not a luxury,” she said, “it is a life-saving intervention.”

Ward said national cooling standards are imperative to guarantee the safety of those who attend and work in public schools, along with residents who live in nursing or long-term care facilities, affordable housing or are incarcerated in prison.

However, she noted the cost of the infrastructure needed to cool all of those facilities means it’s not likely to happen before next summer.

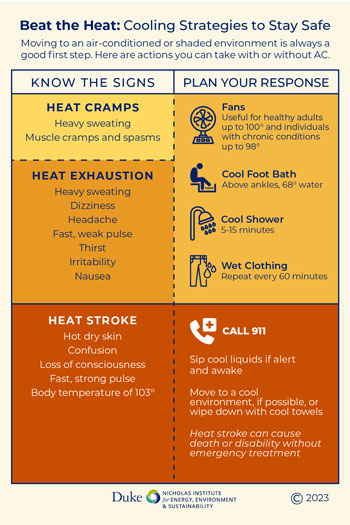

“So in the meantime, as each heat season starts earlier and lasts longer and is marked by greater extremes, we need to be thinking about both short term and long term solutions,” Ward explained. “We have to do a better job at communicating about interventions that don't rely on air conditioning, like taking a cold shower for 10 minutes, effectively lowering your body’s core temperature,” immersing your feet in cold water, techniques developed by the military, along with knowing how to effectively use fans.

“Unfortunately, our over-reliance on air conditioning as a solution has meant that we haven’t adequately educated the public about what to do when they don’t have access to air conditioning,” she said.

Fans alone won’t do the job. Ward said recent research at Duke shows therewill be areas across the country where there are hundreds of hours per year when temperatures are too high for fans to be effective.

Ward said the nation’s extreme heating strategies should connect the dots between all of the relevant federal agencies.

“We have a National Hurricane Center, we have a National Severe Weather Center, we have a National Drought Monitor,” Ward explains. “What we don’t have is an organization that provides federal coordination as well as engagement with regional, state and local agencies.”

Ward said the National Integrated Heat Health Information System established by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration needs to be fully funded.

Federal coordination, she said, can help the public better understand the dynamic effects of heat, exposure and vulnerability, and help determine which policies are needed or will be needed.

Dealing with heat “is on all of us,” Ward said. “And it has to happen at every level.”