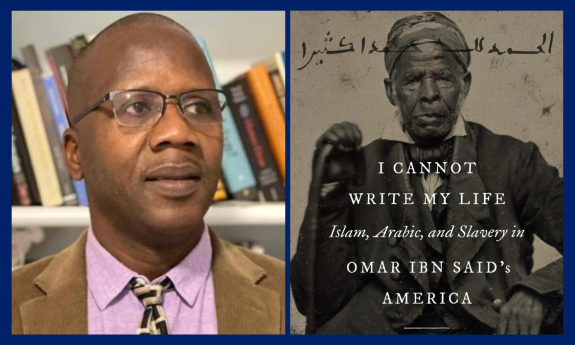

Returning a Voice to an Enslaved Muslim Scholar

Mbaye Lo‘s new book on Omar Ibn Said follows two decades of sharing his life story

Currently in Egypt leading the Duke in the Arab World summer program with a team of students, Lo discussed his interest in Omar’s life, the new book and watching Omar’s story translated into opera.

How did you discover him and what attracted to you about his story?

I talked about Omar briefly in my 2004 book, “Muslim in America: Race, Politics and Community Building,” but researching and writing about Omar actively emerged in 2018 when I was preparing to co-teach a course with Professor Carl Ernst of UNC, on “Arabic Sources on American Slavery.”

It was a unique experience as we worked systematically on collating Omar's writings. Carl then suggested that we should expand the project into a monograph. With the rise of Black Lives Matter movement in 2019, and the enthusiastic engagement of both Duke and UNC students in the seminar class on “Arabic Sources on American Slavery,” Carl's insistence was convincing that “Omar was a witness and a victim of American racism” and such a book “will contribute in enriching our national discourse on race and racism.”

This was the beginning of our partnership on bringing the book to life in two to three years of continuous research and search across national and local libraries.

In retrospect, what did you think was most valuable and memorable about his life and work?

As I immersed myself in reading about the antebellum era and reports on Omar's life, and spending time at Bladen County library, it became clear that the whole story of the ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery was based on fabricated lies. The so-called elites – enslavers, missionary groups and Arabists – colluded to ignore, disregard and distort Omar’s Arabic writings.

Even his name, which he kept spelling out correctly for 50 years, was gotten wrong. He signed his name as Omar ibn Said in all his completed documents, sometime his father and grandfather's name are even presented in these writing, and at times adding his mother as well. But the discourse around him was about his “refusal to return to Africa,” his fervent commitment to Christianity and his criminal background in Africa, etc. None of these claims can be sustained from Omar's writing.

For instance, his 1819 letter to his enslavers urged them to return him to Africa, even specifying the location of his village in the Senegal River; in his autobiography of 1831, he mentioned the great harm done to him by the enslavers who kept him in this country. But none of these was reported during his lifetime. Enslavers and their influential network were interested in presenting him as a benevolent proof for the success of slavery in civilizing and Christianizing the enslaved.

When you were co-writing the book, and as you presented a narrative, did you sense there was something dramatic there that could be translated into an opera or other art form?

Yes, and indeed, Omar makes a palatable source for a historical novel, performance and modern film. As scholars, however, we both overlooked those aspects and wanted to solely and only bring back Omar's voice. This was overdue; we were primarily motivated by ethical consideration of enabling Omar's voice to be heard. But we are delighted that these popular art forms are getting into the game and helping the public have a sense of Omar and his enigmatic life.

About the opera: Did you meet with Rhiannon Giddens and others as she started to put it together? Do you think she saw his life in the same way as you, and does the opera reflect your work?

We did not meet personally with Rhiannon. We were with the opera crew once, and she attended one of our presentations at UNC on the topic. I have also had the honor to interact with the crew at the Boston Lyric Opera, and to share a roundtable discussion with some of the producers in a public forum in Boston.

What was it like to see the opera?

I saw it first at the debut in Charleston during the 2022 Spoleto Festival. I saw it again when it came to town at UNC in February 2023. I think they successfully made some major cosmetic changes following their earlier performances at the Spoleto. What I saw at UNC was beautiful and colorful, and it captured the essence of the story in terms of West African colors, antebellum nuances and the spirits that grounded the development of the early African American culture. I personally applauded the team for making those changes. It brings a deep connection between the opera and our book on Omar.

What did you think when the Pulitzer was announced?

I was not surprised with this announcement; Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels's work in this opera deserves to be recognized for creativity, historical inspiration and promoting humanism as well.

Are you finished with Omar or are you continuing to explore his life and work?

I will continue to work on Omar. It is our hope that more Arabic documents will come to light in the coming days since dozens of Omar's cited or reported documents are still missing. Carl and I have also developed a digital repository at UNC library: “Enslaved Scholars: A Website Repository for Editions of Arabic Texts and English Translations of Writings by Enslaved Muslims in the Americas,” including works they quote. It includes open-source pdf copies of our critical editions of Omar's writing, and links to URLs with images of the original manuscripts. We are adding works of other enslaved Muslim scholars, such as Abdurrahman ibn Ibrahima (d. 1829) and Shaykh Sana See (Panama 1860s) and more. It is also open to other scholars who would like to share their work in the project.