A Hard Fought Legacy

From slavery to lead academic dean in four generations, Milton Blackmon shares his lived Black history

“This is my heritage. I’m proud of that, and it has made me who I am today,” said Blackmon, who learned of his paternal heritage through his late father’s notes and memories, photographs, U.S. Census forms and other records. “We have a family that always wanted to improve, and each generation was able to go further. It shows what you can do with the mindset of striving to gain dignity and building on the shoulders of those who came before you.”

Blackmon never had the chance to meet Melton. Despite the hardships she endured, she lived to be nearly 100. But she died about 10 years before Blackmon was born, he said. Still, her legacy was passed down by Blackmon’s father and it is ever present in Blackmon’s life. When Blackmon earned his doctorate in education in the 1990s, he dedicated it to her memory.

“While she was being whipped, she could never have imagined that over 100 years later, one of her great-great-grandsons would receive the highest academic degree in the same country that denied her the opportunity to read.”

Milton Blackmon

“While she was being whipped, she could never have imagined that over 100 years later, one of her great-great-grandsons would receive the highest academic degree in the same country that denied her the opportunity to read,” he said.

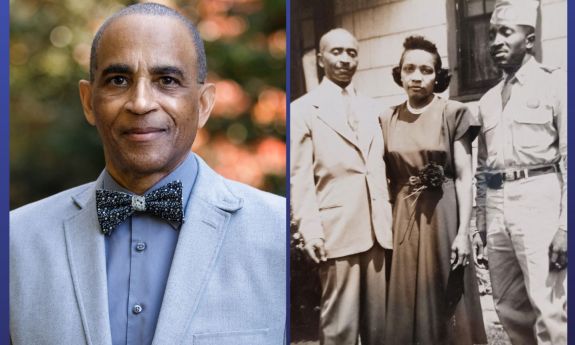

Blackmon had another great-great-grandmother on his father’s side who was enslaved in Mississippi. She had a daughter, Ella Clark (see photo), who married after the Thirteenth Amendment was passed and started a business with her husband.

One of Ella’s descendants was Blackmon’s paternal grandmother Fannie Clark. In one old photo, she stands with her husband Felix and her son Odis, who is wearing his U.S. Army uniform (see photo). Odis was Blackmon’s father.

Blackmon was born and raised in Evanston, Illinois, where his family had moved after leaving the South during the Great Migration. Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Blackmon was involved in the Civil Rights movement as young as age 10. During his fifth-grade year, he and a handful of other Black students were selected to be bussed to an all-white elementary school across town, tasked with integrating the school.

“They had us on the evening news,” said Blackmon, who traveled back to that Evanston school to see its progress 50 years later in 2015. “I’ll never forget sitting in the hallway watching Black kids and other kids freely walking through the halls, and that’s when it really dawned on me that I was one of the first Black students to ever walk those halls.”

As a teen, Blackmon participated in equality marches in his hometown before leaving for Oakwood University in Huntsville, Alabama, where he earned his undergraduate degree and helped start the student chapter of the NAACP. Just like his father, he is a lifetime member of the NAACP. He has also served as the former vice president for the Durham branch of the NAACP, and as a faculty adviser to the Duke student chapter. Blackmon and his wife Juliet both built careers as educators. The couple raised two sons, Jermaine and Jabari, both of whom died in adulthood due to complications from sickle cell disease.

Blackmon said he avoided discussing some of these personal stories with colleagues because he was unsure how they might be received.

“I didn’t know how people would relate to it, but I was pleasantly surprised,” Blackmon said. Colleagues and students have urged him to publish his family history.

“My family history is a part of American history,” Blackmon said. “My great-great-grandparents grew up in slavery. … My parents grew up in an America of segregation and inequality. I grew up helping to integrate America, and my sons grew up in an integrated America. Five generations of my family span nearly 200 years and every era in American history. Black history is American history.”