More than 100 people owe their jobs to Richard Fair and Philip Benfey. Companies they helped create are developing new biomedical equipment and plant-based solutions to climate change.

The two Duke professors are among the university’s most successful examples of transferring innovative ideas from the laboratory to the marketplace. Just don’t expect either of them to say the journey was easy or predictable.

The company carrying Fair’s ideas slogged across the entrepreneurial Valley of Death for 13 years. Benfey’s start-up needed five years. Both men sold companies built on their academic research to larger firms in 2013.

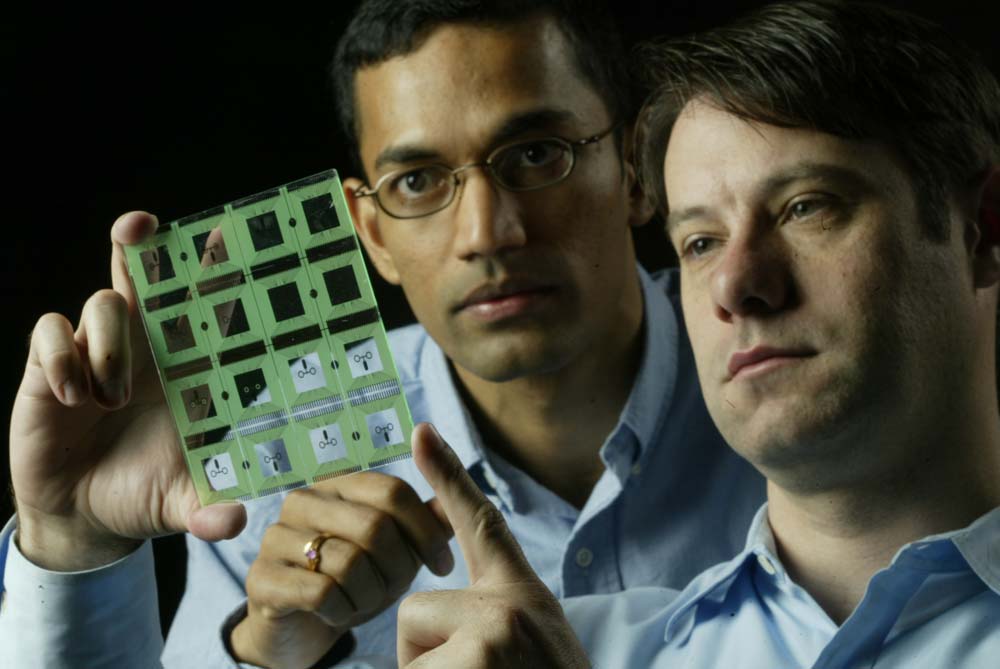

For Fair, the Lord-Chandran Professor of Engineering and a former corporate executive, the process started with a DARPA grant from the Defense Department and two talented post-docs. His small team thought it might be possible to guide tiny droplets of fluid around a tiny device, much the same way electrons move on an integrated circuit chip. “We used droplets like bits of information,” Fair says. However, they lacked the ability to do the things transistors and switches provide for computer chips.