On the Early Front Lines in the HIV/AIDS Fight

Since the early 1980s, Duke staff and faculty showed courage, compassion in the face of the HIV epidemic

Deep inside Duke Clinics, there’s a quiet office-lined corridor that looks like any number of others. It takes the right set of eyes to see how this space with red and pink floor tile is different.

Walking the hallway, Stuart Carr, research program leader for the Duke Department of Pediatrics’ Infectious Disease Division, recalled what the area was like in the early 1990s when it was Duke’s Infectious Disease Clinic, the front lines of the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

This wall wasn’t here, Carr explained. Instead, this was the small lobby where patients sometimes gave fake names to protect their privacy. A scale stood over there, often recording the weights of patients on a steep decline. And Carr pointed to an office where longtime phlebotomist Barlett Humphries drew blood and chatted with patients who were met with reluctance from some caregivers elsewhere.

“That was my favorite job,” said Carr, the clinic’s receptionist in the early 1990s, when HIV patients faced few options and high mortality rates. “It was like, ‘OK, we can’t cure you, we can’t make you healthy, but we can try to make it a lot easier for you to deal with what you’re dealing with.”

December 1, World AIDS Day, provides an opportunity to remember the approximately 40.1 million people lost to AIDS-related illnesses. Through its work improving treatment of HIV/AIDS around the globe to its research into finding a vaccine, Duke has been on the forefront of that fight. That work is part of a proud legacy that started 40 years ago when Duke staff and faculty, some of whom still work at Duke, faced the epidemic with uncommon courage and compassion.

December 1, World AIDS Day, provides an opportunity to remember the approximately 40.1 million people lost to AIDS-related illnesses. Through its work improving treatment of HIV/AIDS around the globe to its research into finding a vaccine, Duke has been on the forefront of that fight. That work is part of a proud legacy that started 40 years ago when Duke staff and faculty, some of whom still work at Duke, faced the epidemic with uncommon courage and compassion.

At a time when important questions about the deadly virus were unanswered, Duke scientists searched for answers. And when many suffering from the disease faced fear and discrimination, Duke doctors and clinical staff created a welcoming space for care.

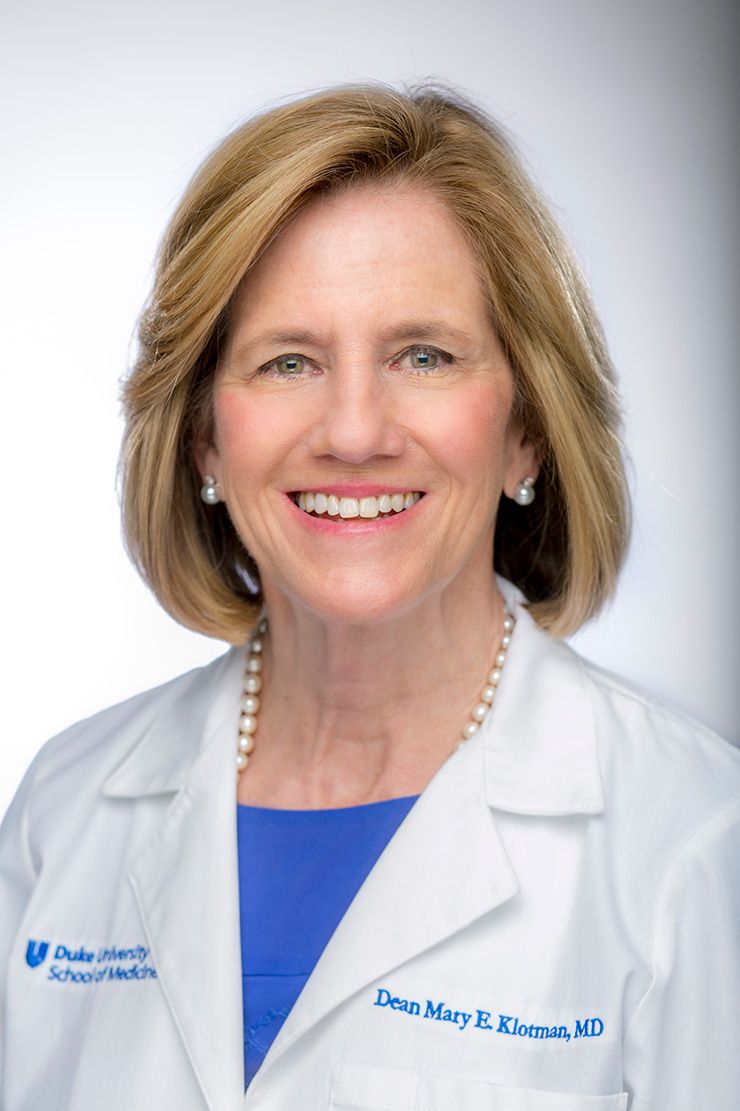

“I would say it drove the passion of a whole generation of healthcare providers,” said Duke University School of Medicine Dean Mary Klotman, who was an infectious disease resident at Duke in the early 1980s before embarking on a career studying HIV. “You saw that at Duke. There were physicians, nurses, social workers and researchers who really became passionate about it and created years of incredible work.”

Fearless Science

In the very early days of the AIDS epidemic in 1983 and 1984, Duke’s Dr. Barton Haynes and his small team were among the first people anywhere to work with the virus. At the time, it wasn’t fully established how the virus spread. What was certain was that it was deadly.

Haynes, now director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, said that, at times, he and research analyst Richard Scearce felt their share of fear while handling specimens through the rubber gloves and glass windows of their BioSafetyLaboratory-4 unit – the most secure biocontainment system available at Duke at the time in the Animal Laboratory Isolation Facility).

But they, like everyone who works in infectious diseases, understood that the opportunity to stop something that can claim the lives of millions was larger than any fear they harbored.

But they, like everyone who works in infectious diseases, understood that the opportunity to stop something that can claim the lives of millions was larger than any fear they harbored.

“We knew it was our responsibility to do the work,” Haynes said. “That’s why we’re here.”

The foundation of Duke’s leading HIV/AIDS research was built in the early 1980s, when Duke scientists such as Haynes tried to slow a burgeoning epidemic by working to define the cause of AIDS.

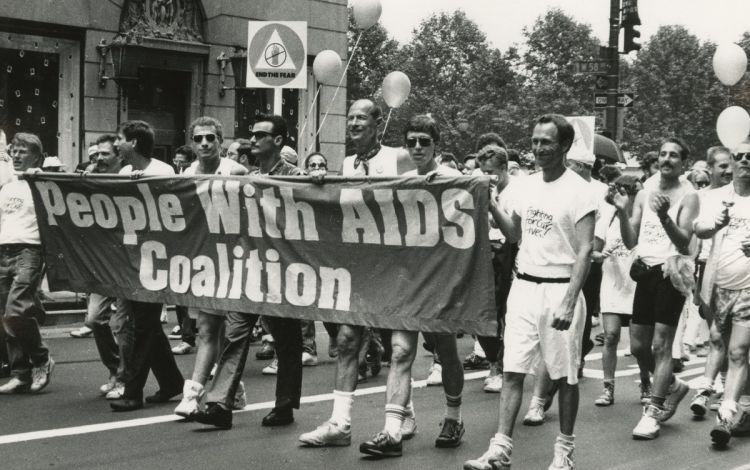

Beyond the fear of contracting a disease for which there was no cure, the fact that gay men made up the most visible segment of HIV/AIDS patients meant some segments in American society felt stopping it wasn’t a priority.

Haynes recalls hearing a few people questioning the value of AIDS-related work and even refusing to shake his hand.

But among Duke leadership, he said, the commitment to fighting the disease was never a question. Haynes and others working on AIDS such as virologists Dr. Dani Bolognesi and Dr. Kent Weinhold received unwavering support from key decision makers, such as then-chair of the Department of Surgery David Sabiston.

“Clinicians and researchers in the Department of Medicine and Surgery really took a stand and said, ‘This is part of humanity and we’re either going to be world class and lead, or try to ignore it and it will be here anyway and we won’t have the expertise to deal with it,’” Haynes said.

That spirit led to Duke scientists contributing to earliest breakthroughs in the fight against the virus. In the early 1980s, Haynes and Bolognesi were early collaborators with the National Cancer Institute’s Dr. Robert Gallo, one of the co-discoverers of HIV.

That spirit led to Duke scientists contributing to earliest breakthroughs in the fight against the virus. In the early 1980s, Haynes and Bolognesi were early collaborators with the National Cancer Institute’s Dr. Robert Gallo, one of the co-discoverers of HIV.

Haynes, through connections with collaborators at the University of North Carolina, supplied Gallo’s lab with specimens from patients with hemophilia who had contracted the disease. These specimens were among those used by Gallo to isolate a number of strains of the virus and demonstrate that HIV-1 was the cause of AIDS.

Meanwhile, Bolognesi, now a professor emeritus of Surgery at Duke, and Dr. Kent Weinhold played a crucial role in discovering that azidothymidine, also known as AZT, was an effective . Duke University Hospital was one of the first two places where AZT was used in clinical trials. In the mid-1980s, Duke doctors led by Dr. Catherine Wilfert also helped to demonstrate that giving AZT to pregnant women could help them avoid passing the disease to their babies.

In the years since, with creation of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, Haynes and several Duke colleagues have continued to do ground-breaking work developing treatments and moving closer to discovering an HIV vaccine that could have a global reach. And many of the lessons learned in the early days of the HIV epidemic helped Duke’s infectious disease researchers contribute to the rapid development of vaccines for COVID-19.

In the years since, with creation of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, Haynes and several Duke colleagues have continued to do ground-breaking work developing treatments and moving closer to discovering an HIV vaccine that could have a global reach. And many of the lessons learned in the early days of the HIV epidemic helped Duke’s infectious disease researchers contribute to the rapid development of vaccines for COVID-19.

“A lot of times in research, you’ve got different groups trying to make a discovery, so there can be some competitiveness,” said Scearce, who retired as a full-time staff member in 2019 but still works as a part-time research associate for the Duke Human Vaccine Institute. “It wasn’t like that with HIV. It really brought scientists together. Everyone realized this would be a difficult project and we wanted to be a part of if.”

Fueled by Compassion

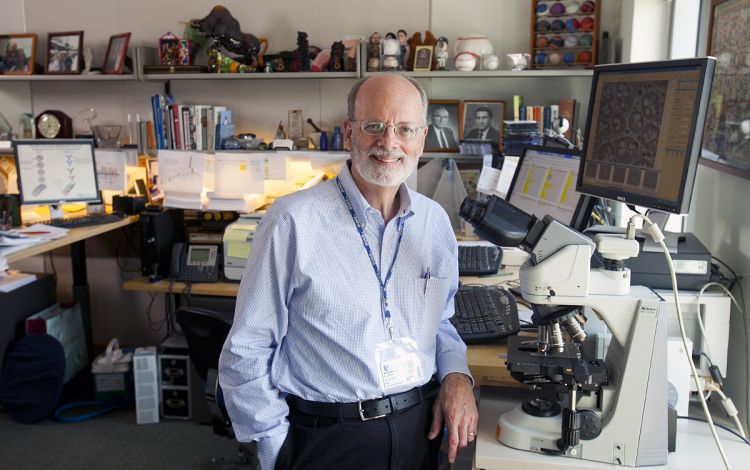

A story Dr. John Bartlett likes to tell about his time at the helm of the Duke Infectious Disease Clinic for patients living with HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s and early 1990s, involves the typists across the hall.

In 1987, five years after Duke first saw patients with the disease, the clinic opened in the lower level of the Orange Zone next to Duke University Hospital’s typing pool.

In 1987, five years after Duke first saw patients with the disease, the clinic opened in the lower level of the Orange Zone next to Duke University Hospital’s typing pool.

“At first, there was quite a bit of apprehension, people would use handkerchiefs to turn doorknobs,” said Bartlett, a professor of Medicine and Global Health.

As time went by, and the typists got to know the patients and saw how the clinic became a welcoming place for people living with hard realities, things changed.

“Before long, the typists were baking cookies for our patients,” Bartlett said. “It was a wonderful thing to see.”

During the 1980s and early 1990s, stories involving AIDS didn’t have many happy endings. There was no treatment proven to stop the disease and a diagnosis often stigmatized people already living on the margins. But during a dark time, this clinic, which had multiple names through the years, became a place where a dedicated team of Duke staff members gave patients doses of hope and acceptance.

“Back then, if you were infected, people would just vanish away,” said Julia Giner, who served as a clinical research nurse in the clinic from 1993 until 2006. “People were afraid and they would just leave a person. We would be their family.”

The work in the clinic, where patients often took part in clinical trials and received treatment for their symptoms, didn’t look like many others.

“We were committed to patient-centered care, and sometimes that meant we did unconventional things,” Bartlett said.

“We were committed to patient-centered care, and sometimes that meant we did unconventional things,” Bartlett said.

Understanding that many of his patients feared being admitted to the hospital – often because their partners wouldn’t be allowed to be there for them – Bartlett’s team did everything it could to keep them in their homes, making house calls and working closely with home care providers to find ways to serve patients.

Many of the clinic’s patients lacked insurance. And some with insurance feared that using it for HIV-related care might cost them their job. So the clinic’s team got adept at finding ways to work with pharmaceutical companies, government programs and other sources to help cover costs of treatments.

And there was a time when some funeral homes in the area wouldn’t handle people who died from AIDS. On a handful of occasions when a patient died in their home, Bartlett put the bodies in the back of his blue Ford Ranger pickup and drove them to Duke University Hospital, which had a crematorium at the time.

Things began to change in the mid-1990s when improved anti-retroviral medications made happier endings possible. Clinic staff members recall seeing previously frail patients putting on weight and regaining the ability to care for themselves. With help from these drugs, Bartlett, who said that during the clinic’s early days he might only know patients for around six months, now has patients he’s known for three decades.

The progress hit home on World AIDS Day in 1996, when clinic staffers listened to a reading of the names of patients lost to the disease the previous year.

The progress hit home on World AIDS Day in 1996, when clinic staffers listened to a reading of the names of patients lost to the disease the previous year.

“In 1995, the list went on and on,” said Patricia Bartlett, wife of Dr. John Bartlett and a former social worker in the clinic. “By 1996, there were about 30 names.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the United States, HIV-related mortality rates have dropped by more than 80 percent since their peak in the mid-1990s.

With the World Health Organization estimating that, at the end of last year, approximately 38.4 million people were living with the disease, HIV remains a global threat to public health. And since 2005, Dr. John Bartlett, through his work with the Duke Center for AIDS Research, has worked with the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Clinic in Tanzania to improve care for HIV patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

But for Bartlett and his colleagues from the early days of Duke’s first HIV-specific clinic, the memories of the care they delivered and the progress they witnessed won’t soon fade.

“I’m quite proud of it,” Bartlett said. “It’s what’s kept me doing this for 40 years and what keeps me looking forward to tomorrow.”

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write working@duke.edu.