How to Persevere When Career Success Comes Slow

Insights on keeping a long-term vision from Duke Nobel Laureate Dr. Robert J. Lefkowitz and author and Fuqua instructor Dorie Clark

Discouraged by slow research progress, Dr. Robert J. Lefkowitz concluded early in his two-year assignment as a researcher at the National Institutes of Health that he did not want to be a scientist.

After a 50-year career dedicated to research into molecular and regulatory properties of receptors that earned him the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Lefkowitz’s career turned out differently than he originally expected.

Lefkowitz would make groundbreaking discoveries about the innerworkings of G-protein-coupled receptors, a class of proteins in living organisms that earned him international acclaim. A third of all drugs today target this family of receptors. It took slow progress to build toward the ultimate achievement in his field, and Lefkowitz learned to grow comfortable with churning through gradual progress.

“When you're really working right at the frontier of knowledge, and you're working on a really important question, it's going to be tough,” said Lefkowitz, the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Professor of Biochemistry and Chemistry at Duke University Medical System. “And that means you're not going to meet with success quickly. I've always been drawn to big, important questions, so progress has generally not been rapid. There are problems that we've worked on for years before we finally crack them and some we never crack.”

Slow career progress is a universal experience that professionals in many positions and across all fields face at some point in a career. Learning how to persevere to achieve success is the focus of Duke Fuqua School of Business instructor and author Dorie Clark’s new book, “The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World.”

Released in September, the book builds on Clark’s LinkedIn Learning course, “Strategic Thinking,” which teaches participants how to take a long-term approach to career planning. Clark’s course is the second most popular on LinkedIn in the last two years, and it’s available to all Duke faculty and staff at no charge through LinkedIn Learning.

Here are some strategies to take when career success comes slower than expected.

Take a ‘long game’ approach

In her book, Clark defines the “long game” as a career planning strategy that prioritizes the big picture of success rather than immediate gratification. Playing the long game often works against our own human nature.

“So much of the world around us is just pushing in the opposite direction about immediate results and needing immediate results, and the idea that if it's not working out right away, well it's not going to work out,” Clark said. “And I think if there's a sense of discomfort about it that people don't like.”

Part of this mindset is setting small goals along the way to accomplish larger objectives in your career that are a work in progress. It also takes patience.

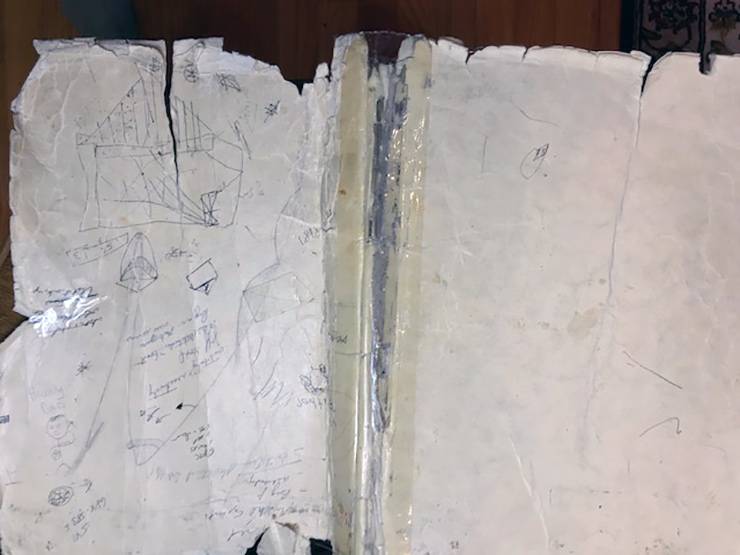

Every year since he joined Duke in 1973, Lefkowitz sits at his desk over the December holidays and reflects on what he accomplished over the previous year. From his desk, he pulls out the same tattered manilla folder held together by Scotch tape that his children drew on 50 years ago and begins looking over goals he set for himself before the start of the year.

Reading through scribbles about specific experimental directions and new interests he wanted to explore, he begins to make a tally to calculate his success rate on those goals. He does not want to exceed a 20 percent success rate, a threshold that lets him know he’s challenging himself to work on ambitious projects.

Then, after evaluating his previous year, Lefkowitz writes down new goals based upon what he didn’t or couldn’t reach. It’s a yearly ritual that helps him track career progress year-over-year and allows him to see ideas germinate and begin to flourish over decades.

“It gives me a sense of continuity in terms of what I’m doing,” Lefkowitz said. “I often tell people there’s no one right way to do research, but what’s worked for me is to push ever deeper on fundamental questions. I have found when I do that, things keep renewing themselves.”

Get around roadblocks

Setting goals alone, though, does not always breed success.

At the start of 2019, Clark set five goals for herself. Among them, she wanted to co-author a book with a famous author, option the rights to her favorite movie and turn it into a movie, speak at a notable industry conference, launch a business column for a major national news outlet, and earn a spot on the list of the Top 50 Business Thinkers in the World named by Thinkers50.

In chapter 9 of her book, Clark details that she accomplished one of the goals by the end of the year; she made the list of top business thinkers. Setting goals is an important part of taking a long-term view in career progress, but it doesn’t always mean everything will according to plan. Roadblocks appear along the way.

The key is to find ways around roadblocks to reach career goals. In her 20s, Clark wanted to earn a Ph.D. and become a college professor. After being rejected by numerous doctoral programs, Clark became a writer instead. Eventually, she began teaching business classes at Duke, an unexpected but successful path.

“So often when we're playing the long game and pursuing long term goals, we are going to have roadblocks and obstacles, and we have to stay resilient and keep bouncing back from that,” Clark said.

This strategy is particularly important for earlier career professionals who have yet to reach sustained success, Lefkowitz said.

Drawing on his days playing softball as a kid in the Bronx, New York, Lefkowitz said he was always nervous to get his first hit at the plate. Once he made contact and got on base for the first time, he often relaxed and had a multi-hit day.

“It does get easier as you go along, because you have some wins,” Lefkowitz said, relating the story back to his career. “Right at the beginning, it's zero to zero. You’ve got no wins; you’ve got no losses. Then, the clock starts, and you start building up losses, you’re 0-2, 0-5. That’s when it’s really tough.”

Lefkowitz recounted his career and how he reached success in his 2021 memoir “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm.”

While he was at the National Institutes of Health, a senior scientist told Lefkowitz the difference between an average scientist and a great one is that an average scientist is successful 1 percent of the time; a great scientist reaches success 2 percent of the time.

Career progress comes the same way, building on small successes over time and adjusting when things don’t follow your plan.

Find your drive

Career success is defined individually. For some, it’s stardom or a certain promotion or salary, while others define success through how they make a difference or other variable.

While Lefkowitz is proud to have earned the Nobel Prize, earning the award was never a goal. Though awards and recognition have come along the way, he learned early on in his career external motivators didn’t matter to him. Instead, he said he is driven by internal goals to reach mastery in his field and the potential to reach the next discovery that could be around the corner.

At a world-class institution like Duke, Clark said it can be easy to compare careers with others, but each person has to find their own drive and reason for their work.

“Ultimately, if we want to play the long game, one of the most important elements is making sure that we are running our own race, that we are not just simply acting out the script of what other people expect or what is societally praised or encouraged within our discipline,” she said.

Finding your drive is critical in moments when success seems far off. Without a reason why to continue, professionals can be vulnerable to giving up too soon, especially when roadblocks stand in the way of success.

“In those moments when you feel like you're not getting anywhere and no one is telling you, ‘Oh hey, great job, keep it up!’ that's the time when we are most susceptible to quitting and to stopping,” Clark said. “And when we do it, it's often premature, and it prevents us from reaching the threshold that enables our message to stick and enables our voice to really be heard.”

It may take slow progress to reach career success, as Clark and Lefkowitz know well, but by setting goals, adjusting your plans and finding your reason why, success is attainable.

“The truth is, if we keep pushing, eventually we can get where we want to go,” Clark said. “It may not look quite the same way that we envision, but good things will happen when we push.”

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write working@duke.edu.