Women in STEM at Duke

Bolstering research and education in STEM fields is a top priority at Duke

Jennifer West’s lab takes up an entire corner of Gross Hall’s third floor.

Among the things West and her team are investigating in the lab is the use of nanoparticles that, when introduced into the body and exposed to infrared light, can heat up and destroy tumors.

Duke has been West’s home since 2012. With its enthusiastic support of her research, it will likely remain so for a long time. But, at other points in her career, West hasn’t felt as comfortable.

At her first-year student orientation at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she was one of few women in an auditorium filled with men. There were times in graduate school and as a faculty member elsewhere when she was her department’s only woman.

“There was a palpable sense that we were the minority,” said West, the Fitzpatrick Family University Professor of Engineering at Duke.

For women who work, teach and study in science, technology, engineering and mathematics – often referred to as STEM fields – this is a familiar scenario. In both education and employment, women are often underrepresented in these disciplines.

A report on the issue, “Solving the Equation,” by the American Association of University Women, states that “diversity in the workforce contributes to creativity, productivity and innovation. The United States can’t afford to ignore the perspectives of half the population in future engineering and technical designs.”

A report on the issue, “Solving the Equation,” by the American Association of University Women, states that “diversity in the workforce contributes to creativity, productivity and innovation. The United States can’t afford to ignore the perspectives of half the population in future engineering and technical designs.”

At Duke, leaders, students, faculty and staff recognize the need to create inclusive environments in STEM fields. In its current academic strategic plan, Duke makes bolstering research and education in STEM fields a top priority and calls for more women to be involved in leading that charge.

“We’re trying to shine a light on science and technology in general,” said Duke Provost Sally Kornbluth, a cell biologist. “But within that effort is a focus on diversifying our workforce and faculty cohort.”

Working for Change

Rochelle Newton was a teenager in the 1970s when she began working with computers, feeding trays of punch cards into hulking contraptions that produced a fraction of the computing power of today’s smartphones.

Rochelle Newton was a teenager in the 1970s when she began working with computers, feeding trays of punch cards into hulking contraptions that produced a fraction of the computing power of today’s smartphones.

During her time in information technology, Newton, now senior systems and user services manager for the Duke University School of Law, has seen a head-spinning amount of technological change.

The rate of change for women in the field, however, has been slower.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that, while women make up 46.9 percent of the nation’s labor force, they hold 25.5 percent of jobs in computer and mathematical occupations, up slightly from 24.8 percent a decade ago. At Duke, women hold 32.5 percent of positions in information technology, down from 33.5 percent a decade ago.

Duke’s Office of Information Technology is trying to expand the range of voices in technology with intern programs that draw students from underrepresented populations, and through “Diversify IT,” a program providing networking and educational opportunities for IT professionals from all backgrounds.

“If women represent half the population, they’re also half of the people using technology,” said Tracy Futhey, Duke’s vice president and chief information officer. “If the technologies they’re using are overwhelmingly designed by men, without involvement from women, they’re likely not going to be as welcoming, usable or interesting as technologies designed with a broader set of perspectives at the table.”

Stories like Newton’s illustrate gradual progress in the field.

Newton was the only woman or person of color at her first job decades ago in Virginia, where she said co-workers played mean-spirited pranks.

“It was really hard, but I was stubborn,” Newton said. “I was going to persevere no matter what.”

As technology advanced, so did Newton’s career. After earning multiple degrees, Newton joined Duke’s staff in 2008. Here, Newton completed professional development programs, such as the Duke Leadership Academy, and became an in-demand speaker on diversity in tech, all while earning a doctorate in higher education administration.

Now, she’s creating the community she lacked earlier in her career with an informal group called “Techs and Collaborators.” The diverse collection of Duke IT professionals meets monthly, discussing upcoming projects and other topics. The group’s guiding principle is inclusiveness.

“I don’t care what color you are, what gender you are, come to the table and bring what you can,” Newton said.

Showing the Way

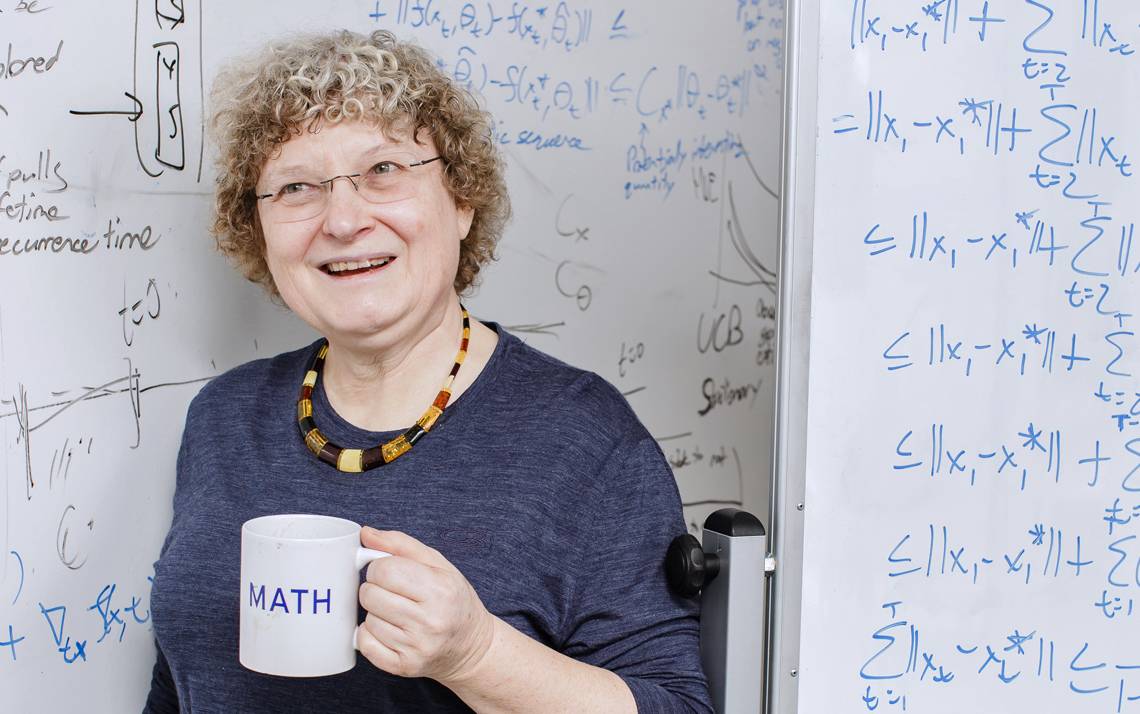

Ingrid Daubechies grew up in Belgium where public education was segregated by gender. It wasn’t until she studied physics in college that she ran into anyone questioning a woman’s place in science.

Ingrid Daubechies grew up in Belgium where public education was segregated by gender. It wasn’t until she studied physics in college that she ran into anyone questioning a woman’s place in science.

“I knew I was good at it,” said Daubechies, the James B. Duke Professor of Mathematics and Electrical and Computer Engineering. “I didn’t see it as an indictment of me, but of them.”

Still, as she began a career in academia, even she experienced self-doubt.

Daubechies worried her outgoing demeanor might be out of place among faculty. But once she met Irina Veretennicoff, a successful Belgian quantum mechanics professor who had a warm, gregarious personality, Daubechies’ concerns were silenced.

Likewise, when Daubechies wondered if motherhood would conflict with her career, her fears were eased when she met acclaimed mathematician and mother of four Cathleen Morawetz.

“As soon as I met one example, it was enough to show me it’s possible,” Daubechies said.

Women who have successfully navigated STEM careers often carry the aspirations of those who hope to follow. That’s why developing strong female role models among the STEM faculty is a Duke priority.

In “Together Duke,” the Academic Strategic Plan released in 2017, the university said it would “aggressively recruit and support women and underrepresented minorities in STEM fields.”

Provost Sally Kornbluth said a key part of the initiative is bringing in elite female faculty members – like Daubechies, who came to Duke from Princeton in 2011 – to inspire students. Research has shown that women with female professors perform better in introductory STEM classes and are more likely to earn STEM degrees than those with male professors.

So the presence of accomplished scientists such as Trinity College of Arts & Sciences Dean Valerie Ashby, a chemist, and department chairs such as chemistry’s Katherine Franz, evolutionary anthropology’s Susan Alberts and statistical science’s Merlise Clyde, looms large.

“I would like women students to see many successful women role models so they can picture themselves being successful scientists one day,” Kornbluth said.

Paying it Forward

On a recent Saturday, laughter spilled from some classrooms in the otherwise empty Physics Building on campus. Middle-school-aged girls and Duke undergraduates clustered around tables, creating exothermic and endothermic reactions with water, baking soda and calcium chloride.

On a recent Saturday, laughter spilled from some classrooms in the otherwise empty Physics Building on campus. Middle-school-aged girls and Duke undergraduates clustered around tables, creating exothermic and endothermic reactions with water, baking soda and calcium chloride.

For Duke sophomore Megan Phibbons, part of FEMMES – Females Excelling More in Math Engineering and Science, the student-run organization that hosted the event – hearing the girls’ happy voices was a thrill.

“It’s really easy to get talked over when you’re a young girl,” said Phibbons, a FEMMES executive board member. “Here, nobody gets talked over. It’s a supportive environment.”

While Duke staff and faculty are tackling the issue of female underrepresentation in STEM fields, Duke’s students are, too.

FEMMES is one of several student groups aimed at broadening the network of science-minded women both at Duke and beyond. That’s important because, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, women received 57.2 percent of all bachelor’s degrees during the 2016-17 academic year but 35.7 percent of those degrees are in STEM fields.

Founded at Duke in 2006, FEMMES engages girls with STEM fields through fun and functional activities led by college students. The program has expanded to other universities and now organizes after school, weekend and summer programs.

“It sets an example of ‘I can do this, too,’” Duke senior and FEMMES Co-President Carolyn Im said. “It shows that there are women pursuing these things, and if you want to do it, you can.”

Have a story idea or news to share? Share it with Working@Duke.