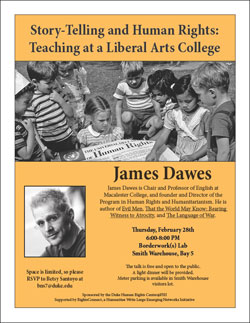

What can human rights studies bring to an academic curriculum? Professor James Dawes will discuss the creation of the Human Rights and Humanitarianism concentration at Macalester College at 6 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 28, in the BorderWork(s) Lab, Smith Warehouse.

The free talk is open to the public, and a light dinner will be served.

An interdisciplinary effort, the concentration covers the history of human rights and humanitarianism; an understanding of the international legal and institutional frameworks governing human rights and the theoretical and philosophical debates about the meanings of human rights and humanitarianism.

Below, Dawes talks about the project by e-mail with Betsy Santoyo, a Duke junior public policy major who is currently working for the Duke Human Rights Center under the RightsConnect Grant.

Q. What inspired you to start a human rights program on your campus and what were the first steps?

Dawes: I created the program because students wanted it. The first step, at a college like mine, is building grassroots support. In fact, that's the first, middle, and last step. At a small liberal arts college, there is no such thing as individualized, go-it-alone, trailblazing leadership -- it's all about building consensus.

Q. What kind of impact would you like this program to have?

Dawes: For the impact that I want it to have, it really isn't about changing the world or anything grand like that -- it's about creating opportunities for my students. I have an imaginary event I play over in my mind: when my students graduate and, let's say, go interview with my friends at HRW, or the ICRC, or similar organizations, what will it look like? Will they be able to demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of the organizations and issues they encounter? Will they be able to show how their liberal arts education relates to human rights and humanitarian work, how their courses in English and Philosophy add something to the organization that straightforward pre-professional training cannot?

Q. What events have been most successful?

Dawes: We have tons of events that run the gamut -- from the usual suspects of human rights lawyers and advocates to less expected photographers and poets, from big, well-known organizations to tiny, surprising ones. I want to show them how big the world of human rights and humanitarian work is, so that whatever their intellectual passion they can find a way to express it in this work.

Q. How important do you think it is for colleges to have a human rights program?

Dawes: I think it's very important for US higher education to have such programs. Students are increasingly passionate about connecting their academic study to issues and work beyond the campus, about connnecting their studies to their broader ethical lives. At its worst, this impulse can reduce to an instrumental preprofessionalism or vocationalism. At its best (and I think this happens in human rights programs because of the unique interdisciplinary demands of such study), this impulse helps students see and, in fact, cultivate the connections not only among classes they're taking across departments and divisions but also among the various roles they play in their local, national, and international communities.