When Nick Tsipis, T'11, MS1, suddenly was stricken with a crushing headache, dizziness, and nausea in Vietnam last summer while volunteering at a sports camp, fellow Duke soccer player and camp volunteer Kendall E. Bradley, T'11, MS1, reactively equated his symptoms with a neurological problem -- something she admits seemed a bit hasty.

Bradley, you see, was fresh off four years in Duke's CAPE Program -- the Collegiate Athletic Pre-Medical Experience -- that exposes promising female undergraduate athletes interested in medicine with hands-on experience in the field. Much of her time in CAPE was spent in Duke's Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center, where she helped to take medical histories and screen patients. She even got to witness brain surgeries up close.

"It's funny, but the first time I got a headache after working in the brain tumor center I thought, 'Oh my God. I have a brain tumor,' " she said laughing. "So with Nick, I told myself, 'you can't think it's neurological because that's all you see. That's all you've been thinking about for years.' "

For Tsipis, that was a good thing. Bradley's instincts helped save his life.

Immediate, excruciating pain

Vietnam Timetable

Tuesday, June 14

7:45 am: Nick collapses while teaching a class in the village of Thuan Hung, Vietnam.

9:45 am: Nick and Kendall arrive at a small community hospital (Hoan My Cuu Long Hospital) in Can Tho. Nick is admitted and spends three days there. His diagnosis is dehydration and G I bacterial infection.

Wednesday, June 15

4:00 pm: Kendall notices a shuffle in Nick's gait and that his pupils are uneven.

Thursday, June 16

4:30 pm: Nick is discharged and returns to his hostel in Thuan Hung.

9:00 pm: Nick experiences an excruciating headache through the night.

Friday, June 17

6:00 am: Kendall insists she and Nick go to an international clinic in Ho Chi Minh City, 5 hours away.

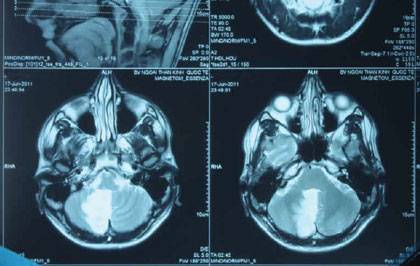

12:30 pm: They arrive in Ho Chi Minh City and Nick has an MRI taken. It reveals a large, white mass on the right side of his brain.

7:30 pm: Kendall contacts Duke doctors Allan and Henry Friedman at the Tisch Brain Tumor Center and emails an iPhone photo of the MRI to them. They insist Nick be medically evacuated to Bangkok, Thailand, to see a Duke-trained neuro-oncologist.

Saturday, June 18

9:30 am: Nick and Kendall are medically evacuated to Bangkok, where Nick is immediately admitted and given medication. He remains in the intensive care unit for 10 days.

Monday, June 27

7:30 pm: Kendall and Nick leave Bangkok and fly home.

Tuesday, June 28

10:30 am: Nick arrives at Duke Hospital and is released the next day.

The two friends, who have known each other since they were freshmen on their respective Duke varsity soccer teams, had been in Vietnam with a humanitarian group coaching soccer and teaching basic academics to children in grades six through nine. On a typical Tuesday morning, that had dawned hot and sunny, Tsipis was lecturing in a classroom when a blast of excruciating pain suddenly shot through his head. The room spun like a dizzying carnival ride. He felt sick and lost balance, catching himself on a chair as he collapsed.

"At first I thought I was just dehydrated, but this hit me out of the blue. Clearly something was wrong," Tsipis related.

After dogged insistence from Bradley to camp organizers, she and a camp leader drove Tsipis to the small community hospital in Can Tho about an hour away over rutted dirt roads. He was given an IV and medication to help stop the vomiting. Bradley recalls that "insects were everywhere" inside Tsipis' room and she constantly brushed them away from his face. Several times in the hallway she noticed rats scurrying about.

During Tsipis' three-day hospital stay, Bradley was frequently on the phone with her mother, Kathryn Andolsek, MD, HS'76-'79, a professor of Community and Family Medicine at Duke; Chris Woods, MD'94, HS'94-'97, '99-'02, a Duke professor of infectious diseases and global health; and David T. Dennis, MD, a global health professor at the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in Singapore. Woods and Dennis both had traveled to Vietnam in the recent past.

Andolsek cleared every procedure and medication with the Vietnamese doctor, who concluded Tsipis was dehydrated and suffering from a gastrointestinal issue, despite an ultrasound showing no signs of one.

Meanwhile, Bradley and Tsipis kept Tsipis' family apprised via Skype. Tsipis felt that all he needed was rest, and was glad to be released from the hospital, even though the headache continued.

"I really thought the headache was from dehydration," he said. "I had been vomiting for 36 hours."

Bradley wasn't so convinced.

The two noticed that Tsipis' pupils were uneven. Bradley also observed a weak shuffle in Tsipis' gait when he walked to the bathroom.

"His pupils just didn't look right so I pulled out my iPhone and used the flashlight to look," she said. "His pupils were reactive, but I still asked the doctor if it was something we should worry about. I learned in CAPE that uneven pupils and difficulty walking could be signs of a neurological problem."

The doctor said not to worry, that Tsipis was just tired and needed rest. The two friends went back to their hostel, where during the night, things took a turn for the worse.

'My head was being crushed'

Tsipis didn't sleep that night because of a menacing headache that felt his head were being crushed. "It was the worse thing I've felt in my life," he said.

Bradley wasn't keen on Tsipis returning to the hospital in Can Tho, where she said, "I fought with them for two-and-half-days to get Nick care."

She decided that they go to Ho Chi Mihn City, five hours away, to seek medical care. Tsipis wanted to tough it out in Can Tho, knowing he was scheduled to fly home in just three days and would see a doctor then. Bradley insisted.

Over the long and bumpy car ride he deteriorated pretty quickly, according to Bradley. "He was laying down with his head on my lap and his headache was getting worse."

At an international clinic in Ho Chi Mihn City, an English-speaking French doctor examined Tsipis and ordered an MRI. The only MRI machine in the city was across town in a derelict hangar-like building.

"There were little medical units off to the sides with motorbikes in the middle," Bradley said. "It was pretty scary."

After Tsipis got the MRI they returned to the clinic and waited nearly four hours for the report. Every hour or so the French doctor asked Tsipis telling questions.

"She asked me if there was any history of stroke or blood clots in my family," he said.

"And if his traveler's insurance covered medical evacuation," Bradley said. "As soon as she mentioned stroke I got very worried."

"It didn't really register with me that I could have had a stroke," Tsipis said. "I'm a healthy, athletic 22-year-old, and there's no history of it in my family."

Once the doctor confirmed the diagnosis of stroke, Bradley immediately phoned the Duke brain tumor center to discuss Tsipis' situation with Duke's acclaimed brain tumor specialist Allan Friedman, MD, HS'74-'80, and noted neuro-oncologist Henry Friedman, MD, HS'81-'83,founders of the CAPE program.

The doctors wanted to see the MRI, but the clinic had no way to digitize and e-mail it.

"So I took a photo of it with my iPhone and e-mailed it to them," Bradley said. "About 85 percent of his right cerebellum was completely white -- a very bad thing." An occlusion in his right vertebral artery had cut off most of the blood supply to Tsipis' right cerebellum.

When they received the e-mail of the MRI, the doctors Friedman grew concerned and asked to have Tsipis get an MRA image of the vessels in his head and neck.

Getting the MRA proved more frightful than the MRI. Bradley describes the hospital with the MRA machine as something out of the Cold War. They entered the dimly lit, dingy, yellowing hallway of the Emergency Department, where to the right she saw a woman lying on a gurney. It appeared the woman had just had surgery.

"She was alone and writhing on the table," Bradley said. "She had drains coming out of her head and one of them was pooling blood on the floor. I immediately turned Nick's chair around." But not before he got a look.

"It was like something out of a horror movie," Tsipis said. "It was one of the most terrifying places I've ever been."

Later on, back at the clinic, the news got worse.

'You've got to get out of there''

The situation was compounded when Allan Friedman recommended that Tsipis immediately be put on several medications, "but the doctor wasn't comfortable with that," Bradley said.

There were two issues the Friedmans were particularly worried about. The first was that if Tsipis went untreated for too long he could have had a second stroke -- this one in his basilar artery -- that would have been devastating. The second concern was that if significant swelling developed from the initial stroke it could have been fatal.

"'You've got to get out of there as soon as possible,' " Bradley says the Friedmans told her.

Bradley thought about worst-case scenarios and asked one of the Vietnamese doctors what the plan was if Tsipis developed a brain bleed. The doctor told her there was a public hospital in the city that "might be able to deal with it, but it was over crowded and extremely busy and Nick probably wouldn't get seen," Bradley said. "So I said, 'You're telling me that if he starts to bleed there's nothing we can do and he's going to die?' And she said 'yes.' "

The Friedmans began the process of having Tsipis evacuated to Bangkok, Thailand, to be treated by Sith Sathornsumetee, MD, HS'00-'07, a neuro-oncologist who trained for seven years under the Friedmans at Duke.

"Henry was on the phone with senators and everyone up the ladder to Hillary Clinton's office in the State Department," Tsipis said. New passports needed to be created because Bradley's and Tsipis' were being held in Can Tho. The offices of U.S. Senators Richard Lugar and Tom Daschle were key to getting the new expedited passports.

Bradley said Henry Friedman stressed to her the direness of the situation.

"He told me Nick had around a 70 percent chance of not making it through the night," Bradley said. "It took me a while to process that. What I could do was keep working to get our passports."

One fear was that a change in altitude pressure during the flight to Bangkok could cause complications.

Tsipis, meanwhile, although still in pain, was able to maintain a sense of humor.

"He didn't know the percentages and I wasn't going to tell him," Bradley said. "But he was messing with me the whole night, and still acting like Nick. That's what I told his parents."

The two were medically evacuated around 9:30 a.m. The flight to Thailand went smoothly, and about two hours later Tsipis was delivered safely to Sathornsumetee at Bangkok Hospital.

"It's amazing to me how far around the world Duke reaches," Bradley said. "It was such a relief to be with 'Dr. Sith,' He had a complete team ready when we arrived and it felt like we were back in an American hospital. Everything was brand new and the level of care was fantastic."

Sathornsumetee ran tests, took an angiogram, and administered the blood thinner Coumadin. Tsipis remained in the intensive care unit of Bangkok Hospital for 10 days. Bradley stayed in Bangkok as well.

Tsipis did not require surgery. Collateral blood vessels in his head have taken over and now supply the right side of his brain. He suffered no long-term side effects of the stroke.

Once in Durham, Tsipis was seen by the Friedmans, kept overnight at Duke Hospital, and released. One month later, he and Bradley started medical school at Duke.

A Heart of Gratitude

"Without Kendall, I can't imagine getting out of there alive," Tsipis said. "Yes, the coaches would have taken me to the hospital in Can Tho, but the doctor there probably would have listened to me when I said I wanted to tough it out. Anything could have happened after that."

So many things fell into place, he said, not the least of which was the fact that Bradley had an international plan on her cell phone, which he did not, and was able to stay in close contact with doctors at Duke, as well as with his family.

"I'm extremely thankful she was on this trip, and that she was trained to do neurological exams," Tsipis said.

He's thankful for Bradley's tenacity with the physicians in Vietnam, for her ability to function on very little sleep, and to deal with so many issues at once, including his insurance company, all the while comforting him and helping to care for him, rarely leaving his bedside.

"There are so many times that things could have gone horribly wrong," he said.

Words aren't enough to thank her, he said. "What do you say to someone who gives you a second chance at life?"

The best way he knows "is to live a worthwhile life," he said. That means becoming the best doctor he's capable of, and modeling Bradley's thoroughness, persistence, and compassion.

"She's going to be an incredible physician," Tsipis said.

Both Bradley and Tsipis currently are undecided about their respective specialties. Bradley is interested in orthopaedics, and Tsipis in oncology, but they both are open to exploring many areas of medicine