Scholar Trades Wrenches For Writing

By Sally Hicks

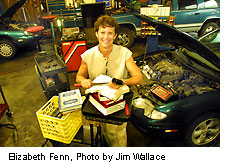

August 30, 2002 | DURHAM, NC -- Few scholarly books begin with heartfelt thanks to an auto-repair shop owner.

But in the foreword of her book, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82, Duke history professor Elizabeth Fenn gives major credit for the work -- and, indeed, her career as a historian -- to Wayne Clayton of Cross Creek BP and Auto Center on Guess Road in Durham.

Why? He was a great boss.

If it hadn't been for Clayton's flexibility, Fenn said, she couldn't have left her eight-year career as an automobile mechanic to finish her Ph.D. -- and to write the book about smallpox that would make her something of a media star in the aftermath of Sept. 11.

Fenn, who goes by Lil, begins work this fall as an assistant professor in the history department, completing a circle that began when she got her undergraduate history degree from Duke in 1981. She headed off to Yale to do graduate work in early American history, but after finishing her doctoral coursework she abruptly changed directions. She moved back to Hillsborough and, after writing a book on North Carolina history with her now-husband, Duke history professor Peter Wood, decided to enroll at Durham Technical Community College to learn auto mechanics.

"I was a case study in downward mobility," she said with a laugh. She said she can't really explain why she made the shift: "I could probably spend years in psychotherapy trying to understand why I did what I did."

It wasn't just a flirtation with the blue-collar life. Fenn spent nearly nine years working in shops around Durham. She said she loved the rough-and-tumble atmosphere of the shop and the satisfaction of working hard. Fenn is no lightweight -- she spent her senior year at Duke living in a teepee on an old tobacco farm -- but being a mechanic is tough, dirty work.

She was beginning to ponder the thought of another career change when she read a French novel called "The Horseman on the Roof," about an Italian nobleman in the midst of a cholera epidemic. It reminded her of some information about smallpox she had encountered while writing her honors thesis on fur traders on Hudson's Bay. Suddenly, she wanted to change topics and finish the Ph.D. she had begun 15 years earlier.

"I felt compelled to write my dissertation," she said. "Could you write this story filled with the pathos and humanity this disease elicits?"

She contacted Yale and found out they would let her write her thesis without repeating any coursework or re-taking exams. After a year of working on the proposal while working part-time in Wayne Clayton's repair shop (hence the thanks in the foreword), she launched into her thesis.

Her dissertation, which became Pox Americana, looks at the smallpox epidemic that swept North America in the years of the American Revolution. It includes evidence that the British, who were largely immune to the disease because they had been exposed to it in the densely populated cities of England, used the virus as a biological weapon.

Fenn said she enjoyed diving back into academic work.

"It was utterly painless. I loved working on my dissertation," she said.

The book might have been just another scholarly monograph if it hadn't been for Sept. 11 and the resulting fears about biological warfare. It was published in October 2001, which made Fenn an obvious choice for media interviews in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks and subsequent anthrax scares. The New York Times published an op-ed by Fenn, George Will wrote about her book and she was interviewed on CNN, the History Channel, Nightline, National Public Radio and even Joan Rivers' radio show. (She was so busy she has even paid somebody else to fix her car.)

"I was reeling," said Fenn, who was teaching at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., at the time. "It was an academic's dream come true, to have a book that makes it big."

The book is in its third printing, and 10,000 copies have been printed, said Peter Miller, publicity director of the publisher, Hill and Wang. Typically this type of serious nonfiction might have one printing of 5,000 copies, he said.

"It's a story. It's a narrative in addition to being well-researched and intelligent," he said. He said he has spotted someone reading it on the subway in New York, and has also received positive feedback from academics. He added that Fenn's years as a mechanic made her work more accessible than the average scholarly work.

"What makes her such a good writer is that she had a foot in both worlds," he said.

On Sept. 11, Fenn was teaching a course on the history of epidemics in America (which she will reprise at Duke this fall) and many of her students were Capitol Hill interns who later had to take the antibiotic Cipro because of the fears of anthrax.

"I see it as an opportunity to educate people about our own history," she said. "Epidemics are catalytic moments in which society reveals itself."

Duke history professor Peter English, who was chairman of her search committee, describes Fenn's hiring as "a real catch" for the department.

"Her book on smallpox is nothing short of spectacular, and she has entered into the national debate that has occurred, unfortunately, in the past months. We're very happy to have her."

After commuting to Washington from Hillsborough for three years, Fenn said she was delighted to be hired by Duke, where she and her husband can be colleagues.

"I never expected to come back to Duke. That would have been presumptuous," she said. But, "You can't imagine how happy I am to be here."

And if for some reason it doesn't work out, she can always go back to fixing cars.

"I do have a fallback," she said.

|