All photos by Robert Zimmerman unless otherwise noted.

BR Goldstein: Landscapes and Systems of Neglect

BR Goldstein was recently in residence in the Ruby's painting studio (Oct 1–25). She completed a new work, hosted tea time and meditation, taught a DukeCreate workshop, and gave a Ruby Friday presentation. Her piece Current Conditions is now on view.

BR Goldstein is a visual artist from Toronto, Canada who has been living and working in Durham for the past two years. Her current focus is painting, but she has also worked in sculpture, performance, and creating large-scale installations in film and video.

Goldstein was in residence in the Ruby’s painting studio for most of October, during which time she created a new work from repurposed material. She also led a DukeCreate workshop on mindful art-making and gave a Ruby Friday talk about the themes and influences of her work.

The text that follows is based on that talk, adapted and edited by Robert Zimmerman.

A Broader Concept of Landscape

When I moved to New York City for graduate work at Parsons, after about a decade as a practicing artist in Toronto, my medium was film and video, but I left the program as a sculptor. Since then, to my surprise, I’ve become a painter, but in my most recent works my “paint” is cloth, burlap, tarp, deer parchment, used fabric, plaster bandages, and thread—materials I use because they have a resonance and immediacy that words cannot match. And although I’m a formalist—more interested in color, shapes, composition, construction and materials than in pictorial representation—I consider myself to be a landscape artist.

It’s a label I resisted for a long time. I grew up in Canada, where it’s hard to escape the idea of colonialism and the colonial gaze. In Canada, if you tell your parents’ friends that you’re a painter, the first thing they’ll ask is whether you like the Group of Seven. These revered artistic icons made wonderful impressionist paintings of the Canadian North, but like so many early twentieth century circles of males painters, they’re also problematic—championing their “new” romanticized vision of the north.

But there’s another Canadian approach to the genre, found in the work of Ed Burtynsky, an artist known for his large-format photographs of industrial landscapes. His work captures something that few people outside of the country seem to realize—Canada has always been a place where resources are extracted at all cost.

Following in Burtynsky’s footsteps, I think of my work as an all-encompassing form of landscape that includes visual markers, histories that have soaked into the earth, and political climates and currents. The connection to the land is especially concrete in Current Conditions, the piece I made during my residency at Duke. I created the work from battered tarps given to me by a neighbor who is a landscaper (tarps have a significance that I’ll explain later).

Minimalist Influences

I love minimalism and the feeling of peace I get from work that’s stripped down to it’s most fundamental form. I’m drawn to the simple shapes, the lines and textures, the distillation in form, in the work of Agnes Martin and Ad Reinhardt.

Richard Serra is another big influence. I appreciate the physicality of his work and the way he allows his process into his sculptural practice by making the means of production explicit. Standing with one of his pieces, you get a sense of the steel-ness of steel and the monumental nature of its production. And the other thing I love about his work in steel is the rust. It’s a slow-motion fire, a memento mori signifying that everything decays.

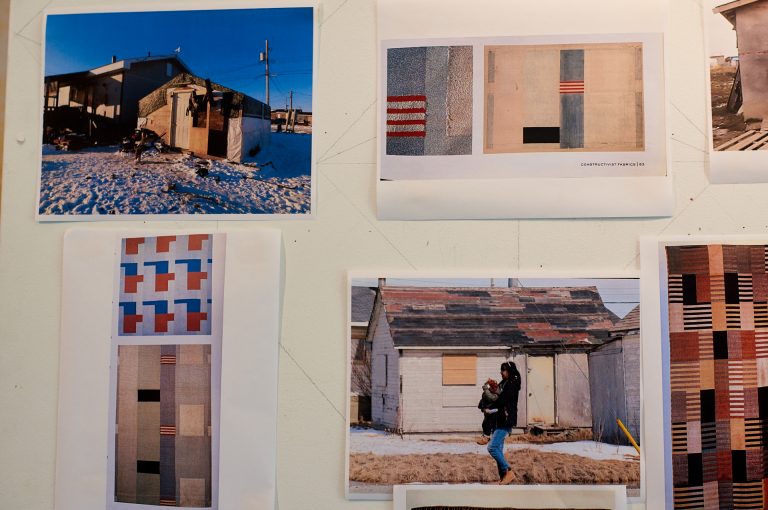

For me, the work of abstraction isn’t spontaneous, it’s a considered process that involves a lot of visual research. For my work in the Ruby I studied tapestry designs by Anni Albers and Margarete Koehler-Bittkow. I also discovered beautiful constructivist textiles by Alastair Morton.

The work of Alberto Burri has been an especially important and moving historical model for me. Burri served as a doctor in the Italian army during the Second World War and spent several years in a POW camp in Texas. In his work I see a visceral representation of his experience of war—the broken bodies he had to repair and the shattered landscape of his native Italy.

Tarps and Systemic Racism

Tarps, the primary element in my new work, have a very specific resonance for me. They are the international signifier of ‘nothing good happened here.’ You see tarps after natural disasters, in refugee camps, and wherever people don’t have the resources to fix homes or cars. Because it’s really important to me to work with subjects that I have an experience of, I’ve focused on news images from First Nations reserves in Canada. They hit the headlines every few years. Like the stories about lead contamination in Flint, Michigan, that flooded news in the U.S. a few years ago, they are reported as if they’re exceptional when they’re actually just the tip of an Antarctic-sized iceberg of malignant systemic racism.

Look at enough of these images and what emerges is the grinding repetition of form and materials. It is an aesthetic that transcends place—although I happen to focus on Canada, it could be blue tarps in Puerto Rico. During my residency, a group came to visit my studio and a woman stayed after to tell me that she’d worked in a refugee camp in Africa. And she said, “Yes, that’s what it looks like.”

The found and repurposed material from my own world and the action of assembling it is a space to illustrate without telling anyone else’s story—a space in which viewers can find their own personal meaning. My hope is that they’ll walk away from my work thinking about the body and its coverings and wounds, about labor and fragility, decay and neglect. Those are the things that haunt me.